Welcome to Postal History Sunday, featured weekly on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with this one (the most recent always shows up at the top).

Several months ago, we explored what it would take to mail a letter from the United States to Switzerland in the 1860s. This time around, I thought it might be fun to look at mail from the United States to France. So, this week is going to be steeped in the postal history part of the story, rather than the surrounding social history.

Either way, you are invited to join

me. I'll do my best to make it interesting and entertaining. There is

no exam at the end and you can feel free to ask questions or, perhaps,

point out things I should correct. Now, let's look at something I

enjoy!

France and the United States of America negotiated a postal convention that went into effect in April of 1857 and provided the guidelines for the exchange of mail through the end of 1869. This treaty set the postage rate at 15 cents per 1/4 ounce (7.5 grams) and allowed for carriage of the mail via American, British, Canadian (after amendment to the agreement in 1861), French and German mail packets (steamships).

Trans-Atlantic Routing Choices

The

postage collected was actually split between the different postal

services based on the parts of the service each country was responsible

for covering. The most expensive part of the service was the Atlantic

Ocean crossing, so it mattered which country held the contract with the

shipping company that carried the mail.

The following is a simplified description of the different trans-Atlantic routes and contracts that mail from the US to France took during this treaty period.

Paid for by the United States (aka American Packet)

- The Inman Line from New York to Queenstown, Ireland and Liverpool, England (green)

- The German owned steamship lines from New York (red) that would go on to Bremen and Hamburg after dropping off French mail in Southampton near London

- The Canadian steamship line (Allen Line) that left either by Quebec or Portland, Maine and went via Derry, Ireland and Liverpool (purple)

- The Havre Line that went direct from New York to Le Havre, France (blue)

The French paid the British (aka British Packet)

- The Cunard Line alternated from New York and Boston, stopping at Queenstown, Ireland and Liverpool (green)

- The Galway Line went from New York to the west coast of Ireland at Galway (green)

Paid for by the French (aka French Packet)

- The French line traveled between New York and Brest, France (blue)

Ships that carried French mails but did not visit a French port were off-loaded from their trans-Atlantic packets under the auspices of the British postal system and had to cross the English Channel. Typically, these mails crossed to Calais, though other entry points (such as Havre) were possible.

Postal Rate Breakdown as They Related to Routes

From the perspective of the postal patron, the rate was 15 cents per 1/4

ounce. The shipping line used did not change the cost for mailing the

letter. Once again, the route only mattered when it came to figuring

out who got how much of the postage. So, the US Post Office cared and

so did the French Post. And, since I am a postal historian, I guess I

care too! Though you could argue that my reasons might need more

justification than the postal clerks of the time did.

Again, you could argue the point. I'm just unlikely to listen.

Since

I collect postal history with the 24 cent stamp, it is actually easier

for me to study items that were double weight (or higher) letters. So, the next several items will have required 30 cents in postage for a letter weighing more than 1/4 ounce and no more than 1/2 ounce.

|

| Table 1 |

Properly paid letters were marked with a credit amount in red. This amount indicated how much of the postage was supposed to be sent to the French from the United States.

The credit amounts shown in Table 1

are for double weight

mail that has been fully paid to the destination in France. For example, if a letter was

sent by a French packet (ship), the US would need to send 24 cents of

the 30 cents collected to France.

Remember, with a prepaid letter, the US postal service

has collected money for all postal services to be used to get the letter

to its destination in France. However, other postal systems were

required to get the letter to its destination. That means some of the

money collected by the United States was necessary to cover services

rendered by these postal systems (the British and French posts). The

credit amount is what is due from

the United States to France to pay for France's (and England's) portion

of the mail

services used. If England was due compensation for its services, it was

up to the French to provide payment from the funds passed to them by

the United States.

United States Packet direct to France

|

| Double rate via Havre |

The item shown above is an example of an American shipping line

providing the trans-Atlantic carriage services directly to France. The New York and Havre Steam Navigation Company (typically referred to as the "Havre Line" by postal historians) sailed between New York and, not surprisingly, Havre.

The 30 cents postage belonged, for the most part, to the United States

because it paid the steam packet line for its services crossing the

Atlantic (18 cents). France was credited only 6 cents to cover its own

mail services starting in Havre until the letter was delivered in

Paris. The remaining 6 cents belonged to the United States for its

'surface mail' from Philadelphia to New York, where it was placed on

board the ship (the Mississippi) that would carry this letter across the Atlantic Ocean.

Other than the circular grid cancels that were used to obliterate the

stamps so they could not be re-used, there are three postal markings on

the front of this envelope that help us understand how this piece of

mail traveled and how the postal systems accounted for the postage.

The red "Phila Am Pkt" circular marking shows the date (Friday, April 26) this envelope entered the mailbag to go across the Atlantic Ocean. The red "6" inside of this circular marking represents the amount credited to France for a double weight piece of mail being carried by a packet under contract to the United States for direct service to France.

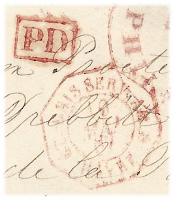

The red octagonal marking reads "Etats Unis Serv Am Havre" and is

dated on May 10, 1867, which represents the date this item was removed

from the mailbag and placed into the French mailstream. The French

clerk recognized this item as paid because the US exchange office had

used red ink for their marking (in Philadelphia). The square marking

with the letters "PD" further confirms that the French were treating this piece of mail as fully paid. This "PD"

marking was an indication to postal personnel that they did not have to

ask the recipient to pay for any of the services rendered.

If this had not been properly prepaid, the marking would have been in

black ink and the amount in the circle would have shown "24" cents to

represent the uncompensated portion of mail service provided by the

United States. There would have been no "PD" marking and the recipient would have been asked to pay for all of the services rendered at the time of delivery.

The one thing that is not obviously referenced by these markings would

be the actual sailing that carried this piece of mail across the

Atlantic. This is where Dick Winter and Walter Hubbard's (North Atlantic Mail Sailings: 1840-1875)

excellent work compiling sailing tables by referencing sailing

documentation in contemporary periodicals comes in handy. The Mississippi of the Havre Line left New York on the 27th and arrived in Havre on May 10.

French Packet Direct to France

|

| Double rate via Brest |

Compagnie Generale Transatlantique (CGT) was a French packet line that

maintained a route between New York and Brest and it held a contract

with France to carry mail beginning in mid-1864. The

route from Brest to New York was designated by CGT as Ligne H, so the

French markings include that label. Since the French were responsible

for paying the steamship line, the 18 cents for the trans-Atlantic carriage

needed to passed to the French postal service. Instead of 6 cents

credited, it was now 24 cents credited to France.

Again, if this is confusing to you, think about where the money is

initially. The sender of this letter purchased 30 cents in US postage

stamps, giving that money to the US postal system. The expenses

incurred for the delivery of each letter could be split into pieces, not

all of which were part of the US post. That which was the

responsibility of another post needed to be paid for, but the money that

was collected in the form of postage needed to be passed to the postal

system that incurred the expenses. Hence the red numerical markings

indicating a credit (24 cents in this case) to the French system.

|

| Double rate via Britain and Calais |

The Cunard Line as American Packet beginning 1868

|

| Cunard Line trans-Atlantic crossing in 1868 |

This next letter serves as is a reminder to

me that a seemingly unrelated act can effect change where we don't

necessarily expect it. The United States and Britain enacted a new

postal convention on January 1, 1868, which reduced the postage rates

between the two. Further, the new convention no longer differentiated

between British and American contract packets. Instead, the postal

service at the point of departure was responsible for the cost of the

trans-Atlantic packet. In other words, every ship carrying mail and

leaving the American ports was an expense for the United States postal

system. The net result for mail to France? Every packet that went via

Britain was now an American packet, so the credit became 12 cents for

Cunard Line ships as the United States now paid them for their services.

Triple Rate Letter

A letter weighing more than a 1/2 ounce and no more than 3/4 ounce would

require 45 cents in postage. Here is an example of a triple rate that was a British Packet via

Britain. The credit marking is for 36 cents to France. Look for the

red pencil marking that reads "36/3" (36 cents credit to France at a 3

times letter rate).

|

| A triple rate letter to France |

If you take a moment to look at this item, it illustrates a couple of

interesting things that could help with reading pieces of postal history

from the period.

Routing and Shipping Directives

The top left of the letter has hand written text (docketing) that reads "per Cunard Steamer of Wed Dec 5th from Boston." It is not uncommon to find these sorts of directions on mail during the 1860's. These directives could have been written by the sender, by the postmaster at the originating post office, by a forwarding agent acting on behalf of the sender or perhaps by the foreign mail clerk at the exchange office. The purpose of this sort of docket could either be to indicate the preferred route, especially if it differed from the postal services default routing, or it could have the intent of trying to show the recipient when something was sent and how it was intended to arrive.

Names and Addresses Removed

If you look at this item closely, you might notice that the name of the

recipient has been crossed out, making it difficult to decipher the

actual name. In many instances, pieces of postal history were acquired

from correspondents who wished to have contents separated from the covering (an

envelope or folded piece of paper). Some went further, attempting to remove any personal

information, such as addresses or names in an attempt to maintain

privacy.

This cover also shows a red "45" at the bottom left. Up to this point, all of the other items only show numbers for the amount to be passed on to France to cover services not rendered by the United States postal system. In the case of this item, the "45" represents the postage required to send the item (45 cents). I am guessing that the marking was applied in Newport, Rhode Island, the post office which postmarked the stamps on December 4.

So, why bother with a "45" marking when there are 45 cents for all to see on the cover? It really seems like extra work, doesn't it? But, if you consider possible scenarios it doesn't seem so odd.

A person walks into the post office with a letter for France. The clerk weights it and informs the sender that it will require 45 cents. The sender pays the clerk and the clerk marks the letter with a "45" and puts it into a pile to be processed later so the clerk can continue to work with other customers.

At a later point in the day, the clerk adds the

appropriate postage and postmarks them. This scenario is not so hard to

believe since I have witnessed the same procedure in my own experience

mailing larger items that require more than a typical amount of

postage. The clerk weighs the item out and writes the postage amount on

the package. I pay and the clerk completes the process of putting

stamps or a meter on the item at some later point in time. Does that

mean this is what happened here? Not necessarily. But, it seems a

likely explanation for something that looks a bit redundant on this

cover.

Short Paid Mail

|

| Insufficiently paid mail treaty as unpaid mail |

So, you think treaty mail is confusing now - just think what it must have seemed like to people when there were different postal rates to each country (and often more than one rate to the same country).

We can

only speculate why the person who mailed the letter shown above used a single 24 cent stamp. But, since it

appears to be a business correspondence it is possible they just

confused this with a letter to England. After all, the rate to England

was 24 cents per half ounce. But, this letter was to France and it

clearly weighed more than 7.5 grams and apparently was less than 15

grams, so the postage required was 30 cents, meaning it was short paid

by 6 cents.

A sensible person might feel as if it would only be fair to collect the

French equivalent of 6 cents and be done with it. But, that is NOT how

it worked at the time with the postal convention in place. Instead,

short paid mail was treated as wholly unpaid, which means the recipient

had to pay the entire rate for the privilege of receiving the letter.

The "16" on the cover represents 16 decimes (1 franc, 60 centimes),

which was due on delivery. Now, the French have collected the entire

postage, but they need to send some money BACK to the United States to

cover the US surface mail expenses. Hence, the 6 in the black New York

marking as a debit to France requesting payment.

So, what happens to the 24 cents in postage collected by the United

States? In this case, the postal service gets to keep it without any

extra services rendered. Does that seem unfair to you? Well, consider

these two things:

1. Mail during this period did not have to be prepaid in order for it to be taken to its destination.

2. A recipient could refuse delivery.

This begs the question - how much mail did postal services carry for

free because it was sent unpaid and the recipient refused delivery?

Still, if this was a legitimate mistake, it does seem a steep price to

pay. The good news is that conventions and postal systems were rapidly

changing to charge only the deficient amount as postage due so that the

postage applied would still pay for at least some of the services

rendered.

Five or Six Times Rate

I'll just let you to enjoy this one by simply showing the exhibit page. I might type a bit more after the illustration.

Here's

a pretty (and larger) envelope with 90 cents of postage, which would

seem to indicate that this was 6 times the 15-cent rate (more that 1 1/4

ounces and no more than 1 1/2 ounces). This letter was carried on a

steamship that went direct to Havre on a US contract ship. So, the

credit amount, for a six-times rate would be 36 cents. But, we muddy

the waters this time with then pen marking that looks a bit like a "30"

and not a "36."

It is

not hard to think of any number of scenarios that explain the

inconsistency - among them the real possibility that this WAS supposed

to be a "36." Rather than engage in speculative postal history, I will

be content with not knowing for certain what rate this envelope was

supposed to be originally. But, I think I have the right of it that

France probably treated it as a five times rate and received a credit of 30 cents. I also believe I

have the right of it that the sender paid for a six times rate with

postage stamps.

You can make up your own story as to how that happened!

Forwarded Mail

|

| An item sent to France and forwarded on to London, England |

It isn't easy to see, but the New York exchange marking at the center right of the letter above shows a "12" and this cover provides an extra puzzle because the date in the New York marking is struck poorly. We are left with the most useful clue coming from the red French marking that gives a Dec 8, 1861 date and reads, in part, "Serv Am."

This is enough to tell me that this piece of mail had to travel

across the Atlantic on an American contract vessel. The two available options from sailing tables are the Inman's Edinburgh

leaving New York on November 23 and a sailing of the Allen Line from

Quebec on the same date. Since both ships arrived at Liverpool on the

7th of December, we can assume the Inman sailing simply because the

Allan Line sailing for New York mail would be highly unlikely.

This appears to be a letter to A.G. Goodall (Albert Gallatin Goodall:

1826-1887), an engraver by trade, who was to become president of the

American Banknote Company (ABC) in 1874, remaining in that office until

his death. As early as 1858, Goodall represented the ABC to obtain

contracts with foreign entities, so travel was not unfamiliar to him.

Goodall was also a prominent freemason who often represented the United

States branches as liaison for related fraternal organizations

worldwide.

Goodall arranged for mail to be sent to the U.S. Legation in Paris

during his travels and clearly, the U.S. Legation in London was also

aware of his itinerary. It was not uncommon for a person traveling to

arrange with an agent to receive mail. That agent could either hold

mail for the client or forward that mail to another location.

In this

case, the Legation in Paris sent the item on without paying the postage

from France to England. The "More to Pay" marking was applied in

London, alerting the recipient and the postal clerk that postage

was due (4d per quarter ounce). It is presumed that the item was rated

as a double rate letter by the British and 8d were collected. The

squiggle at top right *might* be a due marking, though I cannot quite

bring myself to conclude that this mark aligns with a due amount.

The "P.D." marking was applied in France to indicate that postage from

the United States to France had been prepaid, but it did not apply to

the forwarding of the mail.

A quick search for A.G. Goodall in 1861 shows a person by that name returning to New York on the Havre Line's Arago on December 26 of 1861 (New York Times, Dec 27, 1861). So, it seems as if the letter may well have caught him in London.

Where did you learn this stuff?

A

common question that I am asked is, "how did you learn all of these

things?" Well, part of the answer is my good fortune to follow in the

footsteps of others who have done research that makes my own efforts

easier. I thought it might be good to share some of that here. I also

access some of the original postal agreements and conventions of that

time which helps to inform me about what I am looking at.

- The text of the 1857 postal convention can be found along with amendments at this location on the blog.

- Hubbard, W. and Winter, R.F., North Atlantic Mail Sailings: 1840-1875, USPCS, 1988.

- Hargest,G.E., History of Letter Post Communication Between the United States and Europe: 1845-1875, 2nd ed, Quarterman, 1971.

- Winter,D, Understanding Trans-Atlantic Mail vols 1 & 2, APS, 2006.

- Starnes,C.J, United States Letter Rates to Foreign Destinations: 1847 to GPU-UPU, revised ed., Hartmann, 1989.

- Postal Laws and Regulations of the United States of America: 1866, Wierenga reprint, 1981.

- List of Post Offices and Postal Laws and Regulations of the United States of America: 1857, Wierenga reprint, 1980.

Thank you for joining me this week. This entry gives you all a taste of some of the depth and detail that a postal historian may find themselves digging into so they can better recognize and understand what they are seeing when they look at a postal artifact. And, if you're thinking "geez, 'artifact' is a hoity-toity word," all you need to know is that I was looking for an opportunity to put that word in a blog just because I wanted to!

Have a fine remainder of your day and a fine week to come.