Welcome to this week's entry of Postal History Sunday. PHS is hosted every week on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog.

Everyone is welcome here, regardless of the level of knowledge and

expertise you might have in postal history. Each week is a little bit

different - so if this one doesn't speak to you, come back for the next

one or check out prior entries!

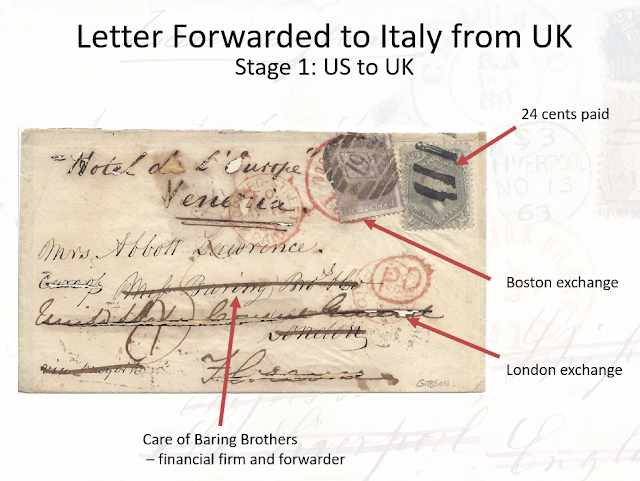

Last Sunday's post was more of what some people might call a social history post. The focus was on the writer and the recipient of the letter and the postal aspect was background information to fill out the story. This week I thought I'd tip the scales and lean into the postal history side a bit more.

We're

going to work backwards this week by looking first at a few covers that

I added to my collection some time ago. None of them cost me much, so I

was willing to pick them up as learning pieces - things that would

encourage me to expand my knowledge and understanding of some area of

postal history I was less comfortable with.

The folded letter

shown above was mailed from Triest, which was then located in the

Austrian Empire. The postage was paid using 16 kreuzer in Austrian

postage stamps. The destination was Bologna, which was in the Kingdom

of Italy in 1867, when this letter was mailed. And, in case you were

hoping for a little social history, Leon Vita Levi was part of the

Jewish community in Bologna and makes an appearance in this 1865 publication ( Monthly Newspaper for the History and Spirit of Judaism).

I picked up this folded letter at the same time as the first. This letter traveled from Triest (again in Austria) to Molfetta, which is further south in the Kingdom of Italy. This time there is 21 kreuzer in postage instead of the 16 kreuzer that was found on the first letter. The letter was mailed in 1865, so the two letters are not that far apart as far as mailing date is concerned.

This, of course, had me asking some questions. If both letters started in Triest and both went to a destination in the Kingdom of Italy, why are there two different postage amounts? Both seem to have indicators that the postage was paid to destination (P.D.).

Then there was this one, mailed in 1870. Once again it was mailed from Triest to a location in the Kingdom of Italy. Firenze (Florence) would be in the Tuscan region of Italy, so it would be further away from Triest than Bologna and closer than Molfetta. This one appears to also be paid to destination (P.D.), but the postage paid was only 15 kreuzer.

- 16 kreuzer to Bologna in 1867

- 21 kreuzer to Molfetta in 1865

- 15 kreuzer to Florence in 1870

What in the world is going on here? I wasn't seeing a pattern, so I went through the possibilities that came to me as I considered these three items.

- Perhaps the postage rate changes between 1865 and 1870 - maybe more than once?

- Perhaps one or more of these letters weighs more than a simple letter?

- Perhaps distance changes the postage rate?

- Perhaps one of these letters was overpaid?

- Perhaps someone has altered one or more of these pieces of postal history? Maybe stamps are missing or added?

Well, I had some options. I could locate pictures and scans of other related items and begin to deduce patterns. Or, I could try to find resources that would tell me what the postal rates between Austria and the Kingdom of Italy were during this time period.

I chose to start with what I knew already and then look for resources that would contain the rates for the time.

What I already understood

I was aware that, prior to 1860, Italy was broken into many Italian States. After the War of 1859, Sardinia (northwest Italy) led the way to unification. The Kingdom of Italy, by the time we get to 1865, consisted of all of Italy except Venetia and the Patrimony of St Peter (around Rome).

I was also aware that Austria, Tuscany, Modena, Parma and the Papal State participated in the Austrian-Italian Postal League. The postage rates in that arrangement included both a weight and a distance component to determine the cost of sending a letter.

Example 1 - Austria to Tuscany during Austrian-Italian Postal League

Tuscany

did not share a border with Austria, relying on transit via

Parma, Modena or the Papal States. There was the possibility for mail

via steamship as well. Regardless, the distance was never going to fall

below 10 meilen (1 meilen = 7.5 km), so the postal rate for the

shortest distance from Austria would never be effective if the

destination was in Tuscany.

| Effective Date | Rate | Unit | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apr 1, 1851 | 6 kreuzer | 1 loth | 10-20 meilen (c) |

| "" | 9 kreuzer | 1 loth | 20+ meilen |

| Nov 1, 1858 | 10 kreuzer | 1 loth | 10-20 meilen |

| "" | 15 kreuzer | 1 loth | 20+ meilen |

| Apr 28, 1859 (a) | |||

| March, 1860 (b) |

(c) - 1 meilen is approx 7.5 km, so distances are 75-150 km and 150+ km

So, I could figure out postage amounts for items between the Austrian

Empire and some of the Italian States. But, once I get to March of

1860, I wasn't so sure. Still, it doesn't hurt to look at examples that

come from a prior postal rate period to help me to get more comfortable

with mail processes in the region.

9 kreuzer per loth 150+ km distance: Apr 1, 1851 - Oct 31, 1858

|

Wien (Vienna) Mar 26, 1858 Firenze (Florence) Mar 2 , 1858 |

The folded letter shown above traveled about 860 km to go from Wien

(Vienna) to Firenze (Florence) in 1858. It's interesting to note that

there is no "P.D." on this letter. But, there is a slash in black ink

on the front that tells us the Florentine postal clerk recognized it as

paid.

Example 2 - Austria to Modena/Parma during Austrian-Italian Postal League

In

the 1850s, both Lombardy and Venetia were part of the Austrian Empire.

That means it was possible for destinations in Modena, Parma and the

Papal States to fall within the shortest distance for calculating

postage. Otherwise, this table looks similar to the last one. We just

add a row for the shortest distance. This was part of the appeal of the

postal league. Postal patrons in the Austrian Empire did not have to

figure out different postage rates for each Italian State.

| Effective Date | Rate | Unit | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jun 1, 1852 | 3 kreuzer | 1 loth | up to 10 meilen |

| "" | 6 kreuzer | 1 loth | 10-20 meilen |

| "" | 9 kreuzer | 1 loth | 20+ meilen |

| Nov 1, 1858 |

5 kreuzer | 1 loth | up to 10 meilen |

| "" | 10 kreuzer | 1 loth | 10-20 meilen |

| "" | 15 kreuzer | 1 loth | 20+ meilen |

| June 11(?), 1859(a) | |||

| May 15, 1862 (b) |

(c) - 1 meilen is approx 7.5 km, so distances are up to 75km, 75-150 km and 150+ km

15 kreuzer per loth 150+ km distance: Nov 1, 1858 - June 11, 1859

Postal rates in Austria changed in 1858 when the empire implemented currency reform. Technically, it was not the rates that changed - it was the value of the kreuzer that changed. But, from a postal historian's perspective the rate amounts are different and the postage stamps also changed.

The distance from Triest to Modena was approximately

340 km, which was roughly equivalent to 45 meilen, well over the 20

meilen mark.

|

Triest Mar 31, 1859 via Modena Apr 2, 1859 |

Routing options may include a northern route via Verona or a Southern via Bologna. However the route didn't make a difference in postage because the distance component was not determined by the actual route a letter took to get from place to place. Instead, distances between places were determined by agreement. It was just understood that Triest to Modena fell in the longest distance calculation.

And what I needed to learn

With my knowledge of the Austrian-Italian Postal League, I had some groundwork already in place. I was also aware that the borders in the region were changing. There was a history of using distance as part of the postal rate calculation. And, of course, it was pretty clear that postal agreements were going to be adjusted after the War of 1859.

It turns out that, as the Kingdom of Italy was being formed, the Austro-Sardinian rate structure was put into place. So, my next step was to figure out how mail between Austria and Sardinia worked.

Example 3 - Austria to Sardinia/Kingdom of Italy Prepaid Letter Rates

The

Sardinians and the Austrians used rayons (or postal zones) to determine

the distance component for their postage rates. Rayons could be

loosely defined by distance from the border. But, postal clerks

referred to lists of post offices to determine which rayon the origin

and destination for a letter were in. In many ways, a rayon based

system was not so different from a distance based system - especially

since actual traveling distance was not considered.

So, a letter might originate in the first, second or third rayon of Austria and travel to the first or second rayon in Sardinia. Please note that there was a third rayon in Sardinia during the 1840s, but Sardinia was reorganized into two rayons starting in 1854.

It certainly results in a fairly complicated table!

| June 1, 1844 | Jan 1, 1854 | Nov 1, 1858(a) | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | 3 kreuzer | 5 kreuzer | < 30 km distance |

| 6 kreuzer | 6 kreuzer | 10 kreuzer | 1st Aus/1st Sard |

| 9 kreuzer | 9 kreuzer | 16 kreuzer | 2nd Aus/1st Sard |

| 15 kreuzer | 12 kreuzer | 21 kreuzer | 3rd Aus/1st Sard |

| 8 kreuzer | 9 kreuzer | 16 kreuzer | 1st Aus/2nd Sard |

| 12 kreuzer | 12 kreuzer | 21 kreuzer | 2nd Aus/2nd Sard |

| 18 kreuzer | 15 kreuzer | 26 kreuzer | 3rd Aus/2nd Sard |

| 10 kreuzer | N/A | N/A | 1st Aus/3rd Sard |

| 13 kreuzer | N/A | N/A | 2nd Aus/3rd Sard |

| 19 kreuzer | N/A | N/A | 3rd Aus/3rd Sard |

| per 1/2 wienerlot | per 1 loth | per 1 loth | |

| Year | Rate | Weight Unit | |

Apr 20, 1859 |

35 new Kr |

loth |

via Switzerland |

Sep 15, 1859 (b) |

|||

May 15, 1862 (c) |

|||

Oct 1, 1867 |

15 kr |

15 grams | N/A |

16 kreuzer per loth Austria rayon II to Italy rayon I : May 15, 1862 - Sep 30, 1867

And

now we can make sense of our first two covers that I did not initially

understand. What I needed to learn is that the old agreement with

Sardinia was simply restarted in 1862 and applied to the entire Kingdom

of Italy. The shaded area in the table can help you focus on the

possible postage rates for mail from Austria to Italy at the time two of

our letters were mailed.

Our first letter traveled about 300 km from Triest (in Austria rayon II) to Bologna (Italy rayon I). By 1867, the rail lines were well established and Venetia was now a part

of the Kingdom of Italy. The railway crossed from Austria to Italy at

Cormons in Austria and followed a route from Udine to Venice to Padova

(and on to Bologna).

Bologna |

21 kreuzer per loth Austria rayon II to Italy rayon II : May 15, 1862 - Sep 30, 1867

via Ferrara, Bologna, Ancona and Foggia by Adriatic Coastal railway (~940km)

|

|

Triest Nov 1 or 4 ? Ferrara Nov 5, 1865 Ancona ??? Molfetta Nov 7, 1865 |

Sure enough, Molfetta was in Italy's second rayon, so the postage was 5 kreuzer more.

Prior

to Austria’s loss of Venetia to the Kingdom of Italy in 1866 during the

Seven Weeks War,

Ferrara served as an exchange office on the Padova-Bologna rail line.

The Adriatic rail line that ran along the coast was available to the

public (and mail carriage) by April 25, 1864. So, it should be safe to

say that this letter was carried on a train via this route.

- Perhaps the postage rate changes between 1865 and 1870 - maybe more than once?

- Perhaps one or more of these letters weighs more than a simple letter?

- Perhaps distance changes the postage rate?

- Perhaps one of these letters was overpaid?

- Perhaps someone has altered one or more of these pieces of postal history? Maybe stamps are missing or added?

For those of you that have read this far - well done! For those of you who skipped to the end - I understand. Postage rates are not something that interest everyone. But, before you go, I want to point out all of the surrounding history that was hinted at as we looked at changes in the postage rates:

- The process of Italian reunification impacted postage rates (and routes). It is a complex period of history for Italy with many interesting stories.

- The currency reform in Austria was a big deal that changes some of the patterns we see in Austrian mail of the time.

- If

you are a person who likes military history, we've got the War of 1859

and the Seven Weeks War in 1866 - both are reflected by the available

rates and routes.

- We can look at the changing influence of Austria in Italy - from spearheading a postal league to actually NOT having any postal agreement for a period of time after the War of 1859.

- Not obvious, but certainly a factor is the development of railways in Italy and increased access to Italy by land (remember the Alps are in the north!).

- And finally, the increased volume of mail and improved transportation between European nations is reflected by simpler, and less expensive, rate structures.

If this still doesn't make you reconsider whether postal rates could be interesting, I'll give you an excuse. I like difficult Sodoku puzzles and I enjoy problem solving and looking for patterns. It's not you. It's me. Sometimes it takes a different personality to enjoy something like this.

Still - I am glad you joined me today for Postal History Sunday. Next week will be something completely different - and even I don't know what it will be at this point. What I am certain of is that I am pleased to share something I enjoy and I hope we all had an opportunity to learn something new.

Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.