It is Sunday and it is also the day before the turning of the calendar from 2023 to 2024. As has been the tradition with Postal History Sunday, I am offering up what I feel are some of the best entries for the past year. Feel free to take the links to the original articles if the description moves you to do so. And, of course, if you think I've got it all wrong and there are others that should have made the list, feel free to let me know.

If you look under the image for each article you will find a "trivia" question. See how many you can answer! Hint - one might find those answers by taking the link for each entry - who didn't see that coming?

Set the troubles aside, grab a favorite beverage and put on the fuzzy slippers. It's time for Postal History Sunday!

People's Choice - The Foolish Desire

|

| 1. In addition to his military service during the Civil War, what was J.W. DeForest' primary occupation? |

The "People's Choice" award was actually very close this year with no entry running away from the competition. The interesting thing, for me, was how some blogs clearly appealed to a wider audience - and they weren't always the ones I expected.

This was actually one of the Postal History Sunday entries this year that was a rewrite of an entry from a couple of years ago. I've learned more since it first appeared and I know that the best writing is actually re-writing. The results here seem to back that up.

As far as a preview is concerned, the main focus is on the contents of a letter written by Harriet Silliman Shepherd to Erastus DeForest during the American Civil War. This Postal History Sunday ranges far and wide, including bull fighting, fancy cancellations, and the chi square distribution. Yes, you read that right. We take our mathematics seriously here too.

11. One Thing Leads to Another and Another Thing Leads to Another

|

| 2. What was the purpose of an exchange office for foreign letter mail? |

While it might seem a bit like I am cheating to get more than eleven blog entries into this list, it's pretty difficult to separate these two because they were intended to be linked in the first place. At least that's my story and I'm sticking to it.

Both of these entries were inspired by a virtual presentation I provided for the Collectors Club of New York. Okay... It was a REAL presentation, not a virtual one. But, I was safely ensconced in front of my computer, just as the audience members were. I appreciate the opportunities to participate in things like this that are brought about by tools like Zoom because I might not have been able to join in otherwise.

There were many positive responses to the content I shared during the presentation, so I thought I would convert some of it to a blog form. If you would like to learn a bit about how I use information from one cover to help me understand another cover, these blogs might be of interest to you.

10. Crossing the Pond and Lighting a Candle

|

| 3. Why was paraffin a popular choice for candle making in the 1860s? |

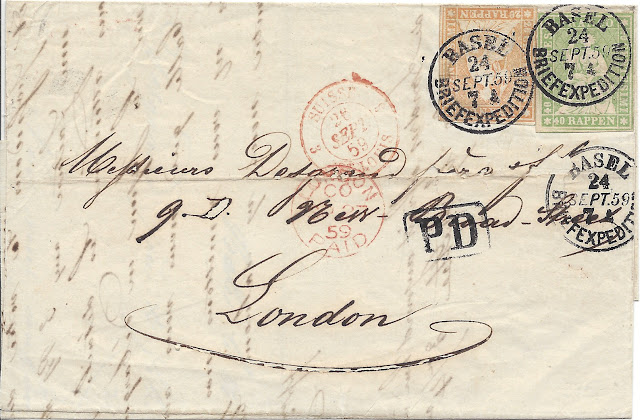

I will admit that some of my favorite Postal History Sunday's to write are those where I allow myself to really explore a single cover fully and thoroughly. This article is actually a very good example of that approach. It starts with a step by step "reading" of the cover to help show everyone how I could determine postal rates, routes and means of transportation. Then, we get to explore the contents and the recipients of the folded letter being featured.

This article does a good job of knowing when to quit, in my opinion. And that's actually one of the hardest things to figure out as I write Postal History Sunday. Clearly topics like trans-Atlantic mail carriage, candle making and the history of a specific geographical region can fill chapters in a book. The trick is to find enough to clearly and accurately reflect enough of each subtopic to be interesting and engaging without crossing the line and becoming dull and overbearing.

|

| 4. Why couldn't the sender prepay all of the postage to send this letter to the US? |

And here is another entry that focuses on a single cover - this time from Rome to Baltimore in the 1850s. Yes, another cover is described in the article, but the point of its inclusion is to help us understand this one better.

I like this entry because it has a nice balance between the postal history and the social history. There's something for everyone - which makes it a good choice for this list. It also fell together fairly easily, which is rarely the case. There are typically a few points where everything hangs up and I have to fight through things. It's noteworthy when that doesn't happen AND the results also read well.

|

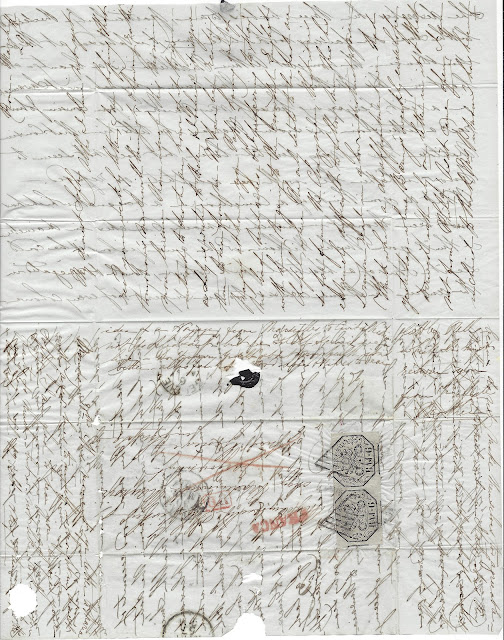

| 5. What were the possible reasons for people implementing cross-writing in letters? |

Postal History Sunday entries that appear to succeed in being accessible to a broad audience often win my favor if I am trying to decide between two choices for the Author's Choice list. Everyone can probably relate to the idea of running out of space - just as the writer of this letter might have been feeling as they tried to put everything they could on a few sheets of paper.

I also enjoy taking advantage of opportunities to feed everyone some postal history facts and information while you are distracted by something like cross-writing. Or maybe I enjoy slipping in some social history while you are distracted by the postal history? Doesn't matter, I am happy either way.

7. Farm Palace

|

| 6. How many plants did the Dickey Clay Mfg Co have at its peak? |

Not every Postal History Sunday has a great deal of postal history in it. Sometimes, the social history rules the day. Regardless, the operative word is "history."

The journey for this article focuses around the advertising images on a mailed envelope instead of the postage rates required or the routes the letter took to get from here to there. I even got to do a little bit with local Iowa history this time around. I also appreciate the opportunity to find a link to my profession as a grower of food. Sometimes the personal connection lends more meaning - and with that meaning there is often better writing.

|

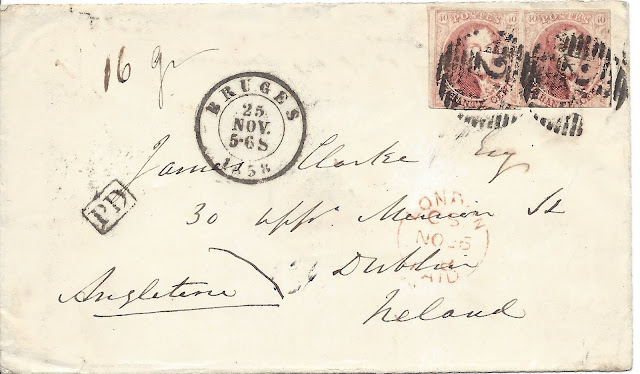

| 7. How did Belgium increase its importance for mail carriage in Europe? |

Sometimes, I get the urge to write about something with more breadth rather than depth. I was able to accomplish that by focusing on several covers that were mailed to Luden and van Geuns in Amsterdam in the 1850s and 1860s. Instead of starting by analyzing a cover, this article introduces us to the people behind the business before taking the time to look at several covers they received while they were in business from locations all over Western Europe.

This particular article is an updated rewrite of an article I shared with the Postal History Journal a couple years before Postal History Sunday existed. Once again, I've learned a great deal since that time, so I like to think I've done the subject proud with a strong rewrite.

5. Night Flight

|

| 8. How long might a letter take to travel from the East to West Coast via surface mail in the 1920s? |

The Author's Choice blog is a chance for me to celebrate (more for myself than for you) a little bit of flexibility in my own writing and learning. For example, it would certainly be far easier for me to write Postal History Sunday entries that focused entirely on the covers that bear the 24-cent 1861 postage stamp. Or, at the least, stick to the 1850-1875 time period where I am most comfortable. But, I often select entries that range further afield from that comfort zone.

That's why an article that features air mail in the United States during the 1920s was an enjoyable stretch for me. There are all sorts of resources available for the early development of air mail, so it's not as if it was horribly difficult to find answers. But, even when information is freely available, familiarity (or lack thereof) plays a significant role when it comes to writing clearly and accurately. I think I did pretty well with this one, even if I do not profess to be an expert on the material, so it gets to be on this list.

4. Humbug!

|

| 9. What percent of items found their way out of the Dead Letter Office in the US? |

Sometimes, I get a feeling about an item and I just know there's going to be something enjoyable to write about. This is one of those cases. As soon as I noticed the word "Humbug" boldly written on this cover, I just had to explore. The result is a an entertaining blog article that falls deep into the subject of dead letter mail - a postal history subject that can quickly become complex but is always interesting. And the idea of undeliverable letters is something we can all relate to - which makes the topic very accessible to most readers.

Another way I can tell this was a good blog was the fact that I continued to be motivated to learn more even after the article was "complete." As a matter of fact, there's more humbuggery in this follow up Postal History Sunday. Maybe, someday, we'll see a third installment where I put all of that and some new discoveries together? I don't know. I guess we'll find out together.

3. Dutch Treat

|

| 10. How long was the 27 cent postage rate for mail from the US to the Netherlands active? |

It never seems to fail. Each time I have done the year-end Author's Choice article for Postal History Sunday, there are three that I struggle to order. On any given day, I might change my mind about where each of these three land. I feel like that is a good sign because it indicates to me that there is some consistency in the quality of my writing (you can decide whether it's a good or bad consistency).

I received a comment regarding this particular entry that it gives a good perspective as to why some postal rates are common while others are not. I must admit that my goal was a bit more simple at first. I wanted to explore why it was that I had to look so long to find any example of this 27 cent rate from the US to the Netherlands. But, as I dug into the topic, it felt natural to compare and contrast some of the options for mail between the two countries at the time.

But, there is actually one more reason why I like this Postal History Sunday article. It felt, to me, like I had unlocked a fresh way to write about this material - a slightly different way to view it. It might not seem all that different to you, and that's fine. But I found some fresh perspective about how to explore things and that means something when you try to write something new each week.

2. Guano Wars

|

| 11. Why was Chincha Island important to the US and Europe in the 1860s? |

This Postal History Sunday is actually one that I've been sitting on for a few years. I've done some research on and off and written a little bit here and there on the topic. But that writing did not get to the point where I pushed the "publish" button unless it was supplementary information for another PHS topic.

That's part of how this blog has worked over the past three and a half years. Most topics are explored over time and the knowledge gets refined as I learn more. Sometimes, I'll write on a topic and publish it fairly quickly - producing a reasonably good article. Other times, I might publish something and then find it lacking when I review a year or two later. That's when I let myself re-write what is written. Then, there are topics like this one - where I just don't want to share it until it gets closer to where I ultimately want it to go.

This particular blog connects my profession as a grower of food to postal history and the history of a region that we often ignore in the United States (the west coast of South America). It would not surprise me if I decided to take this particular topic even further in the future.

1. Forward! and the Mystery of Joseph Cooper

|

| 12. What happened to Joseph Cooper? |

Then there are articles that come together in the matter of a couple of weeks. And, oddly enough this time around, I actually started this particular Postal History Sunday for the prior week and got to a point where I knew there was too much. So, I found a stopping point for that blog and left a teaser at the end of it for this one!

This is the only time out of 176 PHS articles that I stopped writing a blog and then still published what I had - only to follow up with something more the next week. But, it worked. I was able to ride the momentum from the prior week, using that energy to track down Joseph Cooper as best as I was able. I even infected my lovely bride, Tammy, with the search and she helped track some information down too.

This particular entry explores a postal history topic in some detail (forwarded mail) while also taking a look at the social history surrounding not one, but two different people. The trick was to find enough so I could write something that was compelling while, once again, avoiding the temptation of writing too much. I don't know if this one succeeded as well as some of the others did, but the enjoyment of the search stood out for me in this blog - and that's why it lands at number one this year!

And there you are, my list for 2023. I hope you enjoyed this and the blogs I linked here. Have a fine remainder of your weekend and an excellent week to come.

-------------------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.