Welcome to the final Postal History Sunday ... for the month of September! Actually, I really am celebrating this one a little bit because there were a couple of times during the past month that I was not sure I would have the energy to create the weekly post. Yet, here we are, successfully creating another opportunity for me to share something I enjoy and for you to put on those fluffy slippers, enjoy a favorite beverage, and maybe even learn something new!

Before I get started, I would like to extend my gratitude to those who gave me some positive feedback over the past couple of weeks. The timing was excellent and put more fuel in the tank that should turn into more Postal History Sundays.

----------------------------------

How Business or Junk Mail Can Be Attractive

I could be counted among those who currently take most of the things that arrive in the mailbox directly to the recycle bin after a cursory glance. The bulk of what we receive now are advertising newspapers, flyers, and various other types of junk mail. The rest of the mail is typically bills, and those rarely have much going for them from a collecting standpoint either.

So, how ironic is it that an envelope that might very well have been junk mail or a bill is among the favorite pieces in my collection?

Since this envelope no longer has the contents, I cannot be sure if it contained an invoice for an order or a receipt for payment - or maybe just a price list. Frankly, it doesn't really matter, because the graphic design on this advertising cover is enough to keep me happy.

Just the concept of making the artwork appear to be three-dimensional is enough to get our attention. The pencil appears to pierce the paper, revealing an image of the Joseph Dixon Crucible Company's factory buildings. And, they don't miss a trick nor do they leave space unused.

The

pencil is, of course, a Dixon pencil. They use the bottom left to

advertise their crucibles. The top left shows the return address.

Even

the reverse is fun to look at. You won't have many questions about

what they offer after you see one of their advertising envelopes!

Clearly,

this company focused on graphite, turning it into a whole host of

products. Graphite is a crystalized carbon that is a softer substance,

but is resistant to heat. In addition, it is inert (it doesn't react)

with most other metals. If you want to learn more about the basics of

graphite, this site has an easy to read description.

Crucibles are used to melt metals so they can be worked with and formed into other shapes. Given the two properties I cited (resistant to heat and inert with other metals), this makes graphite an excellent choice as a substance to make a crucible! It is my understanding that a well-made graphite crucible could withstand temperatures up to 2000 degrees Celsius.

Oh - and one more tidbit - "plumbago" was the term used

to refer to graphite until the late 1700s. So, in a way, putting

"graphite, plumbago, black lead" on the back of this envelope was a bit

redundant! As always, there is likely more to it than that, but I'll

let you have a go at researching the point if you want!

My

personal exposure to graphite products is largely limited to products to

keep my bicycle working (greasing the chain and keeping cables lubed)

and... of course... the pencil.

Here's the Postal History Part

This

letter was mailed from San Francisco on April 6, 1899 and was received

on the same day in Stockton, California. The 2 cent stamp paid the

postage for a piece of letter mail that weighed up to one ounce

(effective from July 1, 1885 to November 1, 1917). The envelope was

sealed, so this would not have qualified for the reduced postage rates that printed matter were often given.

As far as postage rates and postage routes are concerned, there isn't a whole lot to drive my interest. It was properly paid, it doesn't appear to have been misdirected at any point.

However, there is a point of interest for persons who are especially interested in postal markings (marcophily or marcophilately).

Barry Machine Cancels

As the volume of mail increased, it became increasingly difficult for a postal clerk to use a handstamp on each piece of mail and process the volume of mail coming through their office. Thus, there was motivation for mechanical innovations so more mail could be processed in less time. This particular envelope was postmarked with one such device.

By

the time this letter was mailed, postmarking machines had been in

existence and in use for over twenty years, starting with the Leavitt postmarking machines in the 1870s. And, according to this article by Jerry Miller, there were even some trials for postmarking machines in the U.S. in the 1860s and in the United Kingdom in the 1850s.

Most machines would require that the postal clerk "face" the envelopes so that they were oriented correctly. The idea was that most mail had the stamp placed correctly at the top right of the envelope. As long as the clerk "faced" the letter correctly, the marking would properly cancel the stamp so it could not be re-used.

This particular envelope ran through a machine created by the Barry Postal Supply Company of Oswego, New York. The marking was comprised of two parts.

A dial that gave the originating post office location and a date and time stamp.

And, a portion of the device called a "killer," which was intended to deface the postage stamp so it could not be re-used.

William Barry (1841 - 1915) and his company are responsible for a wide range of markings that postal historians and marcophilatelists can hunt down, collect, and study, to their heart's content - should they desire to do so. This website by the International Machine Cancel Society provides some guidance if you want to hunt down what type of Barry machine cancel you might have discovered.

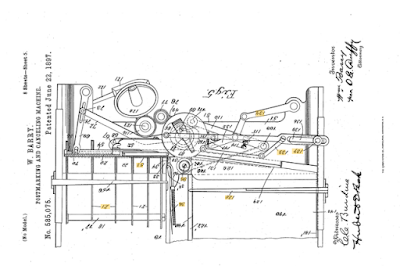

Mr. Barry held a patent (1897) for his cancelling device which can be viewed on the Google patents site. One of the illustrations that was part of the patent paperwork is shown below:

Of note, is the fact that the Find A Grave site provides the death announcement for the correct William Barry. Unfortunately, the photo attached to the site is incorrect. William Barry is listed, in this 2012 book by Keith Holmes, as one of many Black Americans who have successfully created inventions and received patents in the United States.

It

is my understanding that the wide range of Barry cancels can be found

primarily on mail during the 1894-1909 period, so our piece of mail

lands nicely in the middle of that time frame. If you would like to

begin learning about U.S. Machine Cancels, I have found "A Collector's

Guide to U.S. Machine Postmarks: 1871-1925 by Russell F. Hanmer to be a

useful start.

And Here's the Social History Part

The

Dixon Crucible Company was initially founded in 1827 by Joseph Dixon

(1799-1869) and his spouse, Hannah Martin (1795- 1877), according to this site.

The company was not incorporated as the Joseph Dixon Crucible Company

until 1869 (presumably after Joseph's death), remaining open until 1983

when it was merged with the rival pencil maker, Ticonderoga. In fact,

many who read this blog will remember using the yellow Dixon No. 2

pencils while taking standardized tests in school.

His experiments for using graphite to create working crucibles led him to develop the use of graphite for lubricants, pencils, and non-corrosive paints (among other things). The company was initially housed in Salem, Massachusetts, but it moved to its Jersey City location in 1847 (which is where it remained until the 1980s).

|

| Collier's Oct 5, 1901 |

It is tempting to think that pencils were broadly accepted at the time Dixon's company began creating them. However, most people who did much writing used quill and ink pens. It wasn't until the Civil War that the use of pencils became more widely accepted. After all, a soldier could probably keep a pencil stub that could be sharpened with their knife far more easily than a jar of ink and a quill.

By the time we

get to the early 1900s, Dixon's company had a wide range of products,

including products for farm equipment as it moved away from horse power.

|

| The American Thresherman May, 1906 |

Joseph Dixon was an inventor who held multiple patents

for uses of graphite crucibles in pottery and steel making (patents

issued in 1850). He also developed equipment to automate the making of

pencils, including a planing machine (1866 patent) that shaped the cedar

wood so that it could receive the soft graphite to create a pencil.

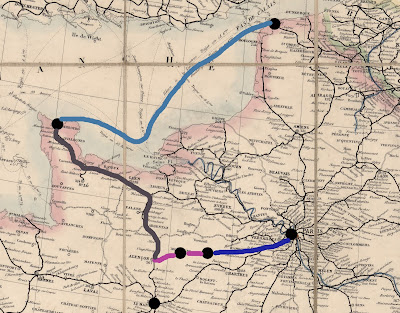

The origination of this cover in San Francisco likely illustrates the company's move in the late 1890s

to start using Incense Cedar that grows in California for the wood

casing of the pencil rather than the Eastern Cedar Cedar found in

Tennessee and surrounding states.

Bonus: A Foray into "Evocative Philately"

In December of 2017, Sheryll Ruecker came up with a brilliant topic idea for an online stamp club meeting. She suggested that we share items that bring strong memories, feelings or images to our minds.

I

appreciated the topic immensely because I believe that many people who

enjoy various hobbies make connections that go deeper than "this is a

neat item." So, what does this particular item bring to my mind when I

look at it? So, in honor of Sheryll, I offer this edited version of

what I shared with the club:

The wooden pencil.

All I have to do is look at the

cover, with the image of a pencil punching through the paper, and I can hear the sound of the pencil sharpener at

the elementary

school when I was a student. I remember that there were times we

would line up to take a turn sharpening pencils and I remember working

desperately hard to use up every tiny bit of each pencil.

How many

people can remember sharpening a pencil for the last time where you

could barely hold on to it to keep it from just spinning around in the

sharpener?

And, what good is a wooden pencil without one of those nice big rubber erasers? There wasn't a 'backspace' key to hit that made what you wrote go away when you made a mistake. After a few seconds of scrubbing on the paper you'd have all of these pills of eraser stubble that you had to sweep off the desk with one quick swipe of the hand.

But, oh, the

frustration when you were overly aggressive with that eraser. How many times did you put a hole in

the paper? Or perhaps you wrinkled the whole sheet up - ugh!

There

were some moments in the classroom where everyone was pretty mellow and

calm. Everyone was working on something and no one seemed inclined to

make a ruckus. I can remember putting my head down on

the desk next to whatever I was working on. I realize only kids can do this because it requires a certain

amount of flexibility and a ridiculous ability to see things a couple of

inches from your face. But, the odd thing about it was that doing this

had the effect of making you feel a bit like you had your own

space, even though you were in a room with 20 to 30 other students and a

teacher.

There is a certain feel and

smell that goes along with wooden flip top desks, paper, pencils and

erasers. I am fortunate that my memories of these times are positive. I

realize some people struggled in school and others were in a school

environment that didn't feel safe to them. I, on the other hand, equate

these sensory inputs with an opportunity to create in a secure

environment. There wasn't a huge rush to get it done. Instead, there

was permission to immerse myself in whatever project was before me.

Sometimes it was math, sometimes it was writing, sometimes it was art.

But, whatever it was, the process often involved pencil, paper and

eraser.

I still write and plan with lead pencils of the 'mechanical' variety.

Pencil sharpeners are no longer found at every corner of a library and I

rely more on my 'portable office' so I can work in any

environment. The traditional wooden pencil is no longer the best

technology for me. But, I still find myself feeling like I'm in the

right place when I pick up a newly sharpened lead and cedar number 2

pencil and put the first figures on the page.

How does this fit in my collection?

If you have been reading Postal History Sunday for a while, you may recognize that this particular item is unlike many of the things I share here. So, why is it in my collection?

Well, one of my projects has been to find postal history items that reflect how a small, diversified farm works. In my opinion, record-keeping is a critical part of the whole operation - and a pencil is one of the few things that writes reliably when you are outside in the rain!

For those who have interest, you can see a sixteen-page exhibit I created that includes the "mighty pencil" on page 14.

------------------------------------------

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Once again, I find that I have learned MANY new things as I explored a single cover with the idea that I would share with you. I hope you were entertained and that you, too, learned something new.

Until next week, my wish for you is that you have a fine remainder of the day and good week to come.