Here we are, sitting at Postal History Sunday number 149! But that's not the important thing as I write this on Saturday. The important thing is that it is raining at the Genuine Faux Farm. For those who do not know, we have been in a drought and it has been a while since we've had any serious precipitation. Each time I look out the window the grass looks a little bit greener and I'm looking forward to seeing the clover get rejuvenated as well.

I promise that I will do my best to concentrate on the business at hand - sharing some postal history, because it is something I enjoy. Hopefully, you will find something here that entertains you or you learn something new. Put on the fuzzy slippers, get a favorite beverage (but keep it away from the keyboard and the paper collectibles) and relax for a while.

Is this something special?

Here we have a folded letter that was mailed at Wasselonne, France on September 2, 1867. The destination was Langnau in the Canton of Berne (in Switzerland). There are two 20 centime postage stamps that pay the postage to get the letter from here to there. Apparently, this was enough because a red marking that shows the letters "PD" in a box was applied in France to let postal clerks down the line know that postage for this letter was considered paid to the destination in Switzerland.

On first glance, this looks to me to be ALMOST a typical simple letter mailed between France and Switzerland during this time period. The postage required for a simple letter in 1867 was actually 30 centimes if it weighed no more than 10 grams (Oct 1, 1865 - Dec 31, 1875). So, this could be an overpayment or, it could be something else.

There is this note, written by a collector (not me) that makes a suggestion that might be worth checking out. It reads "Tarif frontalier, double port." This suggests that this is an example of a double weight letter for the special border rate. This rate was 20 cents per 10 grams, so a prior owner was hoping that they had found something that is very elusive for a postal history collector to find.

Sometimes these notes can point us to something that we might have overlooked, just like the 4th item in this March Postal History Sunday.

The

border rate between France and Switzerland applied when the

straight-line distance was 30 km or less between the origin and

destination. If you look at the map below, you can find Wasselonne,

France, at the top left corner. Langnau, Switerland, is by Berne at the

bottom of the map. The total distance is well over 200 km. Clearly,

this did not qualify for a border rate discount.

So, why would someone think they had found an elusive double-weight letter that illustrated a border rate?

Well, Wasselonne is certainly close enough to the border with Baden (a German State) that it probably DID qualify for some border rate mail. And, it turns out there is a Langnau near Freibourg and it is not terribly far from the France/Baden border. Maybe there is something to that?

The logic here is not necessarily flawed. When I find a letter that does not fit the normal patterns for a simple letter between two countries, it makes sense to check and see if there is some reason for that difference. But, when a letter has more postage than was required for a simple letter we have to remember that one possible explanation is that someone simply put too much postage on there.

Let's just say for a moment that this letter was from Wasselonne to Langnau, Baden. The border rate between France and Baden also required a distance of 30 km, but these two locations are over 100 km apart. Further, the rates between these two postal systems was not as simple as 20 centimes per 10 grams. The border letter rate was 10 centimes for an item that weighed no more than 7.5 grams. If a letter weighed more than 7.5 grams the cost was an additional 10 centimes for each 15 grams.

To get to a cost of 40 centimes, the letter would have had to weigh more than 37.5 grams!

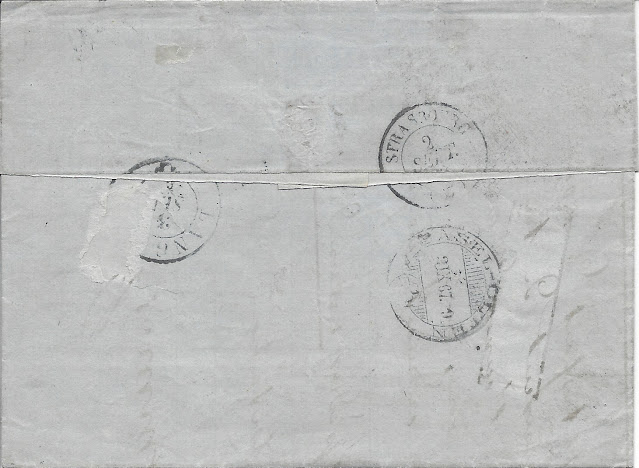

In

case you were wondering if this COULD have been to the Langnau in

Baden, I present the back of this folded letter. It features a postmark

for the Basel-Olten railway in Switzerland (bottom right) and the Swiss

cross can be found on the Langnau receiving postmark (at left). So,

sorry, no. The letter might have passed by Langnau in Baden as it

traveled to Langnau, Switzerland, but that's it.

I can attest that anything other than simple letters (single rate) for European border rates are quite elusive. If you manage to discover one, it is a case for some celebration. Sadly, this is NOT one of those. It is merely an overpayment of the normal letter rate between France and Switzerland.

This is why any explanation written on a postal history item should be written lightly in pencil (if written on the item at all) - preferably on the back. And, yes, I'll be erasing those pencil markings.

In my case, I am pretty happy when I discover a simple letter (single rate) that qualified for the special, reduced border prices. Shown above is a folded letter from Switzerland to France. A 20 rappen stamp pays the special rate and I can confirm that mail between Geneva and Ferney were close enough to qualify for this rate.

If you look carefully at the bottom left, you will see that someone wrote the word "frontalier" on this item as well. At least they were correct this time.

If you would like to learn more about European border rates, this Postal History Sunday does a decent job of explaining them.

How about this one?

Here is a letter that does not have any pencil notations telling us there is something special going on with this envelope that was mailed in 1863 from the United States to London, England. This letter has appeared in Postal History Sunday before and was featured in this January entry. If you want to dive into the details, I recommend you go there.

What makes this cover elusive is the fact that it was carried across the Atlantic Ocean on the Galway Line of ships. And, the only way you can figure that out is by looking at shipping tables and then confirming them by looking at old newspapers that report ship departures and arrivals.

|

| from Walter Hubbard and Richard Winter's North Atlantic Mail Sailings |

The Hibernia, a ship that belonged to the Galway Line at the time, carried this letter. It left Boston on November 3 and arrived eleven days later at Galway. The truly interesting thing for me about this cover is that the Galway Line carried very little of the mail. According to Reports of the Postmaster General from 1864, only 1.8% of the trans-Atlantic mail traveled on Galway ships during the fiscal year. In contrast, the Cunard Line took 43% and the Inman Line 20% across the sea to the United Kingdom.

|

| New York Times, Oct 16, 1863 shipping schedule |

The marking shown below makes the intended ship departure date of November 3 at Boston quite clear. The marking also includes the "Br Pkt," which tells us the ship that crossed the Atlantic was under contract with the British.

In 1863, only two shipping lines would have carried mail under British contract, the Cunard Line and the Galway Line. One was the Hibernia from Boston on November 3. The other was the Scotia from New York on November 4. The Scotia arrived at Queenstown (Ireland) on November 13th, so it would likely have gotten to London on November 14 at the latest. The Hibernia did not get to Galway until November 14 - so it would have been in London later by a day or two.

How about a November 16 arrival date? The London exchange marking on the front is dated November 16. The receiving mark on the back of the envelope is dated November 16. Even the docket that was written at the top of the envelope says it was received in London on November 16.

I think it's pretty clear we have a winner.

Exactly how elusive are items carried from the US to the UK by the Galway Line in 1863? So far, this is the only 24-cent cover I have found that was carried on this line. That certainly doesn't mean there aren't others simply because there is no simple way to identify them.

It does however, fit the definition of elusive.

Kind

of like the rainfall on our farm this year. At this moment, I can

report that we received 1.5 inches of appreciated rainfall, which more

than doubles what we have received since late April. Thank you for

joining me today. I hope you have an excellent remainder of your day

and a fine week to come.

-----------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.