I have been noticing a pattern that has been emerging and maybe you have too. Every seven days there is a Postal History Sunday post on the GFF Postal History Blog. Huh. I wonder how that works?

Let's take all those worries and troubles we have and mix them up with some bread crusts and other kitchen scraps. If we throw all of it to the chickens, they'll have it worried down to nothing in no time! Meanwhile, we can take a few moments out of our day (whichever day it is when you find yourself visiting this blog entry) and learn something new while I share something I enjoy.

---------------------------------------

This

week we're going to actually answer a couple of excellent questions

regarding the postal rates in the United States in the 1800s. But, in

typical fashion for me, we'll get there in a little bit of a

"round-about" way.

Determining size by the sheet

Postage has traditionally been assessed for mail based on two common variables:

- how far a letter must travel to get to the destination, and

- how big the letter is.

The thing that has changed over time is how postal agencies determined distance and size. In the early 1800s the United States determined size by the number of sheets of paper that were in a mail item. As we move to the mid 1800s, the United States changed to a weight-based method of determining size.

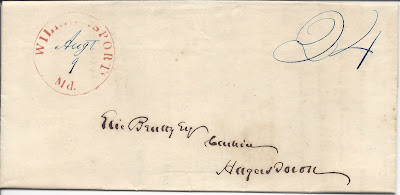

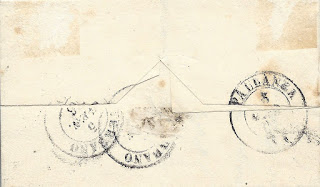

The folded letter shown above is dated August 9, 1839 and was mailed from the Washington County Bank in Williamsport, Maryland to the Cashier at the Hagerstown Bank (also in Maryland) whose name was Elie Beatty.

To cut right to the chase, this letter had FOUR sheets, even though I currently only have one sheet with this item in my collection. That raises the question - how do I know that?

Letter Mail Rates in the United States May 1, 1816 - June 30, 1845

| Distance | Rate | Per |

|---|---|---|

| up to 30 miles |

6 cents |

sheet |

| over 30, up 80 miles |

10 cents |

|

| over 80, up to 150 |

12.5 cents |

sheet |

| over 150, up to 400 |

18.5 cents* |

sheet |

| over 400 miles |

25 cents | sheet |

| *March 3, 1825 |

18.75 cents |

There it is, the postage rate table for letter mail in the United States at the time this letter was mailed. The distance from Williamsport to Hagerstown was (and is) about 7 miles. A "single letter" would require 6 cents in postage. This particular item has a nice bold "24" at the top right, which is four times the single letter sheet. Thus, we can deduce that this item had four sheets of paper total (including this outside wrapper).

One sheet - Longer haul

While I do not have many items from this time period in my collection, I do have a couple that I can show here. The second must have been only a single sheet, but it traveled a much longer distance.

This letter was mailed on August 30, 1819 from Cincinnati, Ohio to Newburyport, Massachusetts, a distance of 915 miles (more or less). A clear marking reads "25" at the top left, which indicates the postage Stephen W Marston would have to pay for the privilege of receiving this missive. The rate per sheet was 25 cents if it traveled over 400 miles, so this qualified as a "single letter."

At this point in time, most mail was sent collect to the recipient and very little was prepaid. I have heard it said by some that the prevailing attitude in some cultures was that it would be offensive to prepay a letter because it might imply that the sender felt you could not manage to pay for your own mail. While I have no idea if that claim is accurate or not, I can accurately report that prepayment at this time was uncommon.

Major changes - July 1, 1845

Things change dramatically in 1845 when the United States switched the measurement of size from the number of sheets to the weight of a letter. Now, a letter that weighed up to 1/2 ounce would be considered a single letter. Each half ounce over that amount would require another rate of postage.

Letter Mail Rates in the United States July 1, 1845 - June 30, 1851

| Distance | Rate | Per |

|---|---|---|

| up to 300 miles |

5 cents |

half ounce |

| over 300 miles | 10 cents |

This brings us to the question about postage rates going DOWN instead of UP (which is what we might consider to be normal in the present day).

The U.S. Postal Service was beginning to see more and more competition from private enterprise that was seeking to provide mail services to the public. One such entity was Hale & Company, which I wrote about in this Postal History Sunday about Independent Mail. The biggest difference is that the US Post Office had the support of Congress, which passed laws that made it illegal for these private entities to carry the mail as they had been doing. At the same time, the same Act of Congress reduced and simplified the postage rates - putting them at prices that were closer to the amounts these private entities had been charging.

The letter above was mailed April 4, 1849 and is datelined from Baltimore with a destination 90 miles away (Martinsburg, Virginia). A big blue "5" shows the postage due. This same letter would have cost 12.5 cents under the old rate structure.

The United States issued their first postage stamps in 1847, ushering in a new normal - the prepayment of postage for letter mail.

Unsurprisingly,

the two denominations for these stamps were 5 and 10 cents - matching

up nicely with the postage rates for mail in the United States at the

time.

Encouraging pre-payment of postage

Once we get to 1851, our postal service in the United States begins to look a bit more like the system we are familiar with. Prepayment is encouraged by setting two different rates for prepaid and unpaid mail.

Letter Mail Rates in the United States July 1, 1851 - March 31, 1855

| Distance | Rate | Per |

|---|---|---|

| up to 3000 miles prepaid |

3 cents |

1/2 ounce |

| over 3000 miles prepaid |

6 cents |

|

| up to 3000 miles unpaid |

5 cents |

1/2 ounce |

| over 3000 miles unpaid | 10 cents | 1/2 ounce |

A letter with the new three cent stamp of 1851 is shown below. I am unable to determine the year date for this letter, but it was clearly a single rate letter that was prepaid in Boston (on its way to Middlebury, Vermont).

It was at this point in time that the trime was issued to help customers pay for the postage with these new, lower rates. For those who do not know what I am talking about - I recently offered a Postal History Sunday focused on the three cent rate and the minting of the three cent coin known as a trime or a fishscale.

By the time we get to 1855, things change yet again! Prepayment is no longer optional and the rates are adjusted once more.

Letter Mail Rates in the United States April 1, 1855 - June 30, 1863

| Distance | Rate | Per |

|---|---|---|

| up to 3000 miles prepaid |

3 cents |

1/2 ounce |

| over 3000 miles prepaid | 10 cents |

Below is an example of an item that traveled over 3000 miles and required 10 cents in postage.

This letter was mailed in San Francisco on April 3, 1863 and traveled via Panama, arriving at its destination in Boston. This letter must have weighed more than a half ounce and no more than one ounce to require 20 cents in postage, paid by two 10 cent postage stamps.

Postage rates from 1863

To answer the question that was asked about postage rates further, here is a table that shows the next several rate periods. Starting in July of 1863, the distance component was removed from the rate calculation for mail inside of the United States.

Letter Mail Rates in the United States

| Effective Date | Rate | Per |

|---|---|---|

| July 1, 1863 |

3 cents |

half ounce |

| October 1, 1883 |

2 cents |

|

| July 1, 1885 |

2 cents |

ounce |

| November 2, 1917 |

3 cents |

ounce |

| July 1, 1919 |

2 cents | ounce |

| July 6, 1932 | 3 cents | ounce |

The trend for the reduction in postage rates actually continues until 1885. There is a short interruption during World War I when an increase was used to help fund the war effort. Once we get to 1932, the trend of increasing rates would slowly begin. The next rate increase would be in 1958 (to 4 cents).

Because I haven't shown you a picture for a short bit - here is an 1898 example of the 2 cents for letter mail weighing up to one ounce rate.

You asked about letter rates going up and down in the United States and....now you know!

Bonus Material!

Because I am feeling generous right now, I thought I would add a little bonus material to the mix today.

Let

me remind you of our first postal history item that I shared at the top

of this blog. It just so happens that there are MANY pieces of mail

still out in the world for collectors to find that went to Elie Beatty,

Cashier for the Hagerstown Bank. It is because of correspondences like

this one that postal historians are often able to learn more about how

the postal services worked during the time the correspondence was

active.

The Hagerstown Bank correspondence has value for historians who study banking systems too. Elie Beatty was a well-respected cashier and was apparently quite talented at his job. The site linked in the prior sentence gives us this summary:

"The historical significance of the collection lies primarily in the insights it offers to the operations of a prosperous regional bank during a tumultuous period in United States banking history. The antebellum decades witnessed a series of banking crises, most notably the Panics of 1819 and 1839, recurring recessions and depressions, and the famous "Bank Wars." The financial and political upheaval, combined with disastrous harvests during the 1830s, wreaked havoc on Washington County, Maryland, and caused the Williamsport Bank to suspend specie payments in 1839. Despite the prevailing economic climate, the Hagerstown Bank emerged as a stable financial institution with considerable holdings."

Is it possible that the Washington County Bank in Williamsport is one and the same as the Williamsport Bank referenced in this paragraph?

Elie Beatty's story can certainly be expanded upon, but I will suggest that you can take the link and read the summary there if you have interest. If there was a doubt as to Beatty's dedication to his job, I will add the following from the site linked above.

"Beatty resigned his position on April 23, 1859, citing "feeble health and the infirmities of age." Beatty died on May 5, 1859 at the age of eighty-three."One last tidbit comes from the Hagerstown newspaper (The Herald and Torch Light) on April 17, 1878.

Elie Beatty served as Cashier for most of his tenure at the bank, but he was president of the bank for just under two years - being pressed into service at the death of the current president of the bank in 1831. While it is clear that Beatty was a highly competent individual, is it possible that he was happier with the hands-on management aspect rather than being the person with the final decision making power? That may be a question for another time and another person - but it is intriguing nonetheless.

-----------------------------

There you have it! You've just spent some time taking another journey as we explore postal history together on a Sunday. Whether you are also a postal historian or just an "innocent bystander" who just couldn't help but take the journey with us, I am glad you joined me in the process.

Have a wonderful remainder of the day and a good week to follow.