Welcome once again to Postal History Sunday on the GFF Postal History blog!

This week, in honor of Memorial Day in the United States, I will break with tradition and not tell you how to pack your troubles away so you can enjoy a few moments reading this blog. Instead, I'm going to be presumptuous and tell you to push your own personal troubles out of the way so you can ponder what it means for individuals to die in military service for their country (it does not matter which country) or for people to be injured, displaced, and terrorized by war.

But, even as we ponder, I hope we can also learn something new and still enjoy as we explore the postal history hobby.

---------------------------

Many

postal historians explore the process of mail delivery during periods

of conflict. My own interests often do not focus on wartime postal

history. However, I recognize that these are periods of time where I

can study how postal services worked to adapt as they attempted to solve

problems brought about by strife between nations and peoples. I also

understand that conflicts often serve as milestones for change that are

reflected in postal history. Therefore, it is important that I have an

awareness of these events.

By now, you also know that I like a piece of postal history that leads me to a good story. When it comes to stories, wartime can provide numerous compelling plot lines that feature normal, every day people - rather than the rich and famous.

At the time this letter was mailed, the cost of mailing to a foreign destination from the United States was 5 cents for every ounce in weight. A five cent stamp from a series known as the "Overrun Countries" was applied to pay the postage required.

A Letter to a Relative in the Armed Forces

H.

Edgar French, of New Castle, Indiana, wrote a letter to Flight Sergeant

Geoffrey French of the Royal Australian Air Force. He posted this

letter on March 14, 1944. I have not determined how Edgar and Geoffrey

might have been related, but it seems clear that they must have been.

There were no contents with this envelope, so who knows what Edgar wrote

about? It could have been stories about a favorite niece or reports on

the family's Victory Garden. That's something I'll never know.

The Lease-Lend Act is more commonly referenced as the Lend-Lease Act (but who's quibbling?). This legislation provided President Roosevelt with the authority to send materials, such as food, supplies, and weapons to Europe without breaking the United States' neutral stance. The legislation went into effect on October 23, 1941 about a month and a half before the attack at Pearl Harbor and the end of that neutrality.

This

particular envelope was printed by a company called Advertisers Press

which operated out of Des Moines, Iowa. Apparently, they printed a

series called "Victory Envelopes" for public consumption. For those who

have interest, there are people who study the myriad designs and

printers who created patriotic envelopes during World War II. From what

I have heard, the definitive book on the subject was written by Lawrence Sherman and would be a useful acquisition for those who would like to pursue the subject further.

A "Merry Chase" Cover

Some time ago, I showed an item in a postal history discussion group that traveled to many places before catching up to the recipient. My description was that the the letter went on a "Merry Chase." Several people found that amusing and it has encouraged me to use that term any time I find an item that had fairly complex travels to get where it needed to go.

First - to England

The first address for this item was to England, but that address has been crossed out and then covered up by a label that has only been partially removed. In itself, this is not a surprise since most Allied military personnel in the European theater likely had a mailing address in England from which their mail would be forwarded to their active duty location.

The England location is also not surprising because the Royal Australian Air Force was largely under the control of the Royal Air Force (British). So, while Flight Sergeant French was a R.A.A.F. member, he was part of an R.A.F. squadron.

Next - to Italy

The removed label likely held information on the first target for forwarding and it is possible the pencil notations at the bottom could also provide clues. But that may not matter because we do know that Flight Sergeant French was part of the 104th RAF Squadron, which was stationed in Foggia, Italy from December 30, 1943 to October 31, 1945. So, it makes sense that the letter was forwarded on to Foggia.

I could leave it at that, but I want to point out to you that going from England to Italy was not a simple matter. There was a war on in 1944.

The

territory in red would have been areas controlled by the Allies and

blue would have been Axis control. Mail from England to southern Italy

would have had to go the long way around to get to where it was going! I

am sure specialists in World War II mail would be able to tell me (and

you) how the letter likely got where it was going. But, I am not that

specialist! If you are, feel free to let me know what you know about

it.

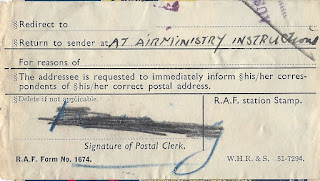

The next obvious pieces of postal information that I can readily decipher are on the back of the envelope.

The first postmark reads: Field Post Office 217 - May 12, 1944

We can take a guess that this might be the Field Post Office in Foggia for the British forces. There are numerous sources that track this sort of information, but I was not able to locate one that provided me with information to confirm that this was located in Foggia.

And now back to England

It is my guess that the label shown above was affixed giving instructions that this letter should be returned to the sender at the British Field Post Office (note that this is an R.A.F. form, not R.A.A.F.). At a guess, this was sent on to the R.A.F. (British) Air Ministry Instructions in England who THEN sent it on to the Australian Airboard (administrative arm of the R.A.A.F).

Why was it forwarded? French's plane had gone down on April 17. Sadly, he was no longer available to read letters addressed to him. The report of his demise can be found later in the blog.

A long trip to Melbourne, Australia

Now, the Australian Air Force postal service had to find a way to get the letter back to the writer.

The second marking reads: R.A.A.F. Base P.O.N. 15 July 21, 1944 M.E.

Here's where I find myself out of my element. I am sure those who study military mail could decipher more of this than I can.

This is the step in the process where I think the purple handstamp that reads: Return to Sender on Australian Airboard Instructions R Silvester Commanding Officer was applied. The Australian Airboard was the administrative arm of the Royal Australian Air Force and was located in Melbourne, Australia at the time. So I will conclude, unless proven otherwise, that this marking was applied in Melbourne.

Sadly, I cannot tell you if the letter sat in Australia for months before being forwarded on or if it got part way before it stalled at some out of the way location. There are no markings to record those travels.

Back to the beginning - Indiana, USA

The final marking on the back reads: Feb 9, 1945 H.E.F.

This

would be a handstamp applied by Mr. H. Edgar French. We can assume he

received the letter he had written almost eleven months earlier and the

"Merry Chase" ends.

Indiana to England to Italy to England to Australia to Indiana. A Merry Chase indeed.

Five of Six Crew Members Lost

What

must it be like to be notified that a family member is lost in war?

This letter did not return to Mr. French until February of 1945, so I

can guess that he had already been notified by family that Geoffrey's

plane had ditched in the ocean near Corsica and that he was among the

five crew members that were lost. Perhaps his family was just getting

over the initial grief - and then this letter comes back in the mail to

haunt them.

The RAAF Aviation History Museum

provides a summary of the action that took the life of Flight Sergeant

Geoffrey Charles French. The original work to compile this information

by Alan Storr can be found here.

In honor of the Flight Sergeant and all others who have served and are no longer with us, I take the liberty of quoting that site for the content regarding his loss:

Service No: 422484

Born: Ryde NSW, 27 July 1917

Enlisted in the RAAF: 22 May 1942

Unit: No. 104 Squadron (RAF)

Died: Air Operations: (No. 104 Squadron Wellington aircraft LN928), off Corsica, 17 April 1944, Aged 26 Years

Buried: Unrecovered

CWGC Additional Information: Son of Albert Edgar and Elizabeth Ida French, of Hornsby, New South Wales, Australia.At 2307 hours on 16 April 1944 Wellington LN928 took off from Foggia aerodrome to attack a target at Leghorn, Italy. The following messages were received from the aircraft: 0130 hours- Landing at Borgo with engine trouble; 0206 hours – preparing to ditch, and 0209 hours – now ditching at position 42.20N 009.57E. The position was in the sea near Corsica. When the aircraft ditched, Flying Officer Gilleland was forced out of the escape hatch by the inrush of water. No other survivors were seen. He reached a dinghy and later saw a light being shone upside of the dinghy. He was rescued when a Catalina was sighted and attracted that afternoon. It was later recorded that the 5 missing members had lost their lives at sea.

The crew members of LN928 were:

Sergeant Ronald Adams (1047206) (RAFVR) (Wireless Operator Air)

Flying Officer Leslie Albert Denison (418224) (Navigator Bomb Aimer)

Sergeant William Fox (1586899) (RAFVR) (Navigator)

Flight Sergeant Geoffrey Charles French (422484) (Navigator Bomb Aimer)

Flying Officer William Campbell Gilleland (421900) (Pilot) Rescued, Discharged from the RAAF: 11 July 1945

Warrant Officer William Barry Ryan (413446) (Air Gunner)

Above

is a Vickers Wellington aircraft (bomber) that would have been similar

to the one Geoffrey French served on. Image taken from the wikipedia

open source photos pages.

-----------------------------