Welcome to this week's edition of Postal History Sunday, hosted on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. Everyone is welcome at this place, where the farmer shares a hobby he enjoys. Questions are always welcomed - and it doesn't matter whether yours is from the perspective of someone who knows very little about postal history or someone who is an expert in the field.

For the time being, let me encourage you to put on your fluffy slippers and grab that favored beverage. Take your troubles and smear some bacon grease on them, then let the neighborhood dogs at them while you read Postal History Sunday By the time you are done and the dogs are done with your troubles, there might not be much left to concern you!

How did this mail get from here to there? That's one of the key questions a postal historian asks each time they encounter an old letter or other piece of mail. Sometimes the answer comes from documents that outline the regulations and procedures of the time. And, if we are looking at mail from the 1850s and 1860s, we can look at the envelopes and covers themselves for evidence of the travels required to get from point A to point B.

You don't have to be a super sleuth to look at the envelope shown above to figure out that this letter probably originated in Boston, Massachusetts and reached its destination in London, England. The clues are everywhere. The envelope is personalized, showing "C. Burrage & Co Boston" (see bonus material at end of this blog) in the preprinted design, so we can assume this is who the letter came from. There is a red Boston postmark dated June 12 and there is a London postmark dated June 23. The letter is addressed to B.J. Lang in London.

Yes. I think that much is pretty simple.

There is actually another clue at the top left. The docket reads "Str Persia N.Y. June 13th."

If

you are a person who knows a bit about world geography, but nothing

about postal history of the time, you might be a bit confused by the

docket. There IS a town named Persia in New York state, so that might

distract us. And, no, I don't think this letter would go from Boston to

Persia (Iran) and then to London - so that's not on the table.

What the docket is referring to, however, is a sailing of a ship called the Persia from the New York harbor on June 13. So, this letter started in Boston, went to New York, boarded the ship Persia and went across the Atlantic. We just happen to know, based on historical references, that the Persia dropped off the mail at Queenstown (Cobh, Ireland). The mail then went by train to Kingston (by Dublin), crossed to Holyhead and then went by train to London.

The question then is why there are no markings on this envelope for New York, Queenstown, Kingston, Holyhead or maybe even the ship called the Persia?

That's a good question - thanks for asking!

When nations exchange mail

In the mid-1800s countries who wished to exchange mail would either establish postal treaties with each other OR they would rely on finding an intermediary to get the mail from here to there. The piece of letter mail shown above was sent under a postal agreement that was established in 1848 between the United States and the United Kingdom.

One of the details often determined by these treaties was the identification of the post office locations in each country that would serve as exchange offices. With the initial treaty in 1848, there were only two exchange offices identified in the United States that were allowed to exchange mail with the United Kingdom. These post offices were in New York City and Boston. In the United Kingdom, we see mentions of Liverpool, Southampton, and London.

The

exchange offices in each country were charged with processing the mail

that was outgoing to and incoming from the exchange offices of the other

country. They would check that postage was properly paid, determine

the best route to send the letter, put a marking on the envelope, and

then place the envelope into a mailbag that was traveling to the

destination exchange office. They were also tasked with filling out

proper documents that would include the accounting of the contents in

the mailbag.

Once that mailbag was sealed, it was not opened until it reached the destination exchange office.

And

that's the simple answer as to why we don't see any postal markings

between Boston and New York. This letter stayed locked up in a mailbag

between the two exchange offices.

More Mail Volume = More Exchange Offices

By

the time we get to the 1860s, the volume of mail between the United

States and the United Kingdom had grown. As a result, additional

exchange offices were established that could handle mail between the two

postal services.

Additional articles were added to the postal convention in 1853 that added Philadelphia to the list of U.S. exchange offices. By 1859, Chicago, Portland and Detroit were authorized to be exchange offices in the US while Cork (Cobh), Dublin and Galway in Ireland were added for the U.K.

The biggest motivator for adding new exchange offices between the US and the UK was simple. New steamship companies with contracts to carry the mail traveled between established ports that did not work well with the existing exchange offices. Once the Canadian Allan Line started service from Quebec/Portland to Liverpool, it made sense to establish exchange offices in the midwest (Chicago and Detroit) so mail would not have to go via New York or Boston to travel on those ships.

The letter above originated in Davenport, Iowa and went through the Chicago exchange office. I know this because the "3 cents" marking at lower left is known to be a Chicago marking (and because mail from Iowa typically went through the Chicago or New York offices). This letter was not taken out of the mailbag once it was placed there in Chicago until it got to the London exchange office.

Not Just the US & UK

Shown above is a nice folded letter sent from Zurich, Switzerland to Mulhouse, France in 1868. The postmark for Zurich is dated May 7 and there is a Basel, Switzerland postmark on the back dated May 8.

In this case, the exchange offices were Basel and Mulhouse.

Unlike the case for mail between the US and the UK, the distances between the exchange offices were not necessarily all that great. After all, France and Switzerland share a border. In fact, Basel, is a border community with France and it was not at all uncommon for border community post offices to also serve as exchange offices. If you think about it, this makes perfect sense. With a little imagination, you could see how a postal worker could cross the border and deliver a bag of mail to France to the clerks there and then return with a mailbag full of items from France to Switzerland!

And, here is just such a letter. St Louis is the community just to the northwest of Basel in France and this exchange office would handle a significant amount of mail that was leaving Switzerland in the 1850s and 1860s. This letter would eventually travel on to Paris for its ultimate destination.

By the time the 1865 convention between France and Switzerland came into effect, rail transportation had proliferated to the point that there were many options for the speedy transit of mail. As a result, the list of exchange offices gets pretty long! The list above are the exchange offices on the French side of the border at that point.

This actually gives a person an opportunity to hunt for some different things. Remember, in addition to mail that was traveling between the big cities like Zurich and Paris, there would be mail between small towns by the border.

The letter above was received by the French exchange office of Bonneville in the Duchy of Savoy (southeastern France). This exchange office is not frequently found, so it can be a bit of a game to try and find items that clearly went to some of the smaller offices between these two countries. It is made easier by the fact that France was particularly interested in their exchange offices placing easy to find red markings on the letters taken out of mailbags at their exchange offices. Switzerland, on the other hand did not necessarily provide markedly different handstamps to indicate that the marking was applied by an exchange office.

If

you have interest, feel free to click on the map above to see some of

the points of interest near the borders of France and Switzerland. The

Duchy of Savoy is outlined separately because it was actually a part of

Sardinia until 1860, but became a part of France thereafter. You can

find Bonneville to the southeast of Geneva, Switzerland.

Knowing What You're Looking For

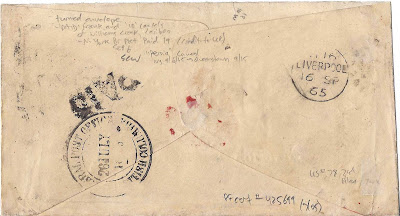

Just because the US and the UK did things one way, that did not necessarily mean things would look exactly the same between the US and other postal services. The Prussian Mails favored a square marking that was typically in blue ink during the latter half of the 1860s. Aachen was the site of the exchange office, residing on the border with Belgium. The Boston marking, on the other hand, seems to be pretty similar to what we're used to seeing with the US/UK mail.

Once again, Boston and Aachen were the exchange offices and this letter stayed in a mailbag for its entire trip between the two. This item would have traveled through the United Kingdom and Belgium to get to Aachen, but no markings will be found to give us this evidence. Instead, we have to use knowledge of how mail was carried between these exchange offices to fill in the blanks.

For those who are curious, the letter above also went to New York' harbour where it boarded the HAPAG Line's Germania.

The mailbag was offloaded at Southampton, England and taken across the

channel to Ostend, Belgium. From there, it crossed Belgium by rail to

Aachen, in Prussia.

Before you get too comfortable, consider this letter from the same time period from the UK to Austria (via the Prussian Mails). The round PD (London) marking served as the exchange marking for the UK, while the big, blue round marking was applied in Aachen for the Prussians.

Markings

could differ between pairs of nations - and sometimes no marking was

applied at all by the receiving country. Though, usually, the sending

country would be required to put some sort of marking on the item to

indicate whether postage was paid in full or if postage was due. It was

all a matter of two postal services coming to some sort of agreement

that made sense to each of them how they would communicate with each

other. And that, as much as anything, should explain to you and me why

agreements would limit the exchange of mail to a subset of all of the

post offices in each country. The special processes required for

foreign mail exchange required additional training - training that was

not going to be possible to give to every clerk in every post office.

Bonus Material

The envelope above is likely from the company J.C. Burrage in Boston. This resource places the business at No 3 Winthrop Square in Boston. The company itself is referenced multiple times in the Burrage Memorial and the company served as merchants for woolens (see pages 127, 132 and 152).

The recipient, B.J. Lang, was a musician, conductor, pianist, teacher, and composer. We'll probably go deeper into this person's biography in a different Postal History Sunday.

There is something else about this piece of postal history that is interesting and I think we'll also cover that in a future Postal History Sunday. Can you figure it out? Here is an earlier post that talks about the mail between the US and the UK - it might help.

I hope you enjoyed today's entry. Have a great day and a wonderful week to come.