Welcome to Postal History Sunday on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and GFF Postal History blog.

It's time for us to set our troubles aside for a short time while I

share something I enjoy with you. Perhaps we'll all learn something new

in the process and, if we do this right, we might even forget where we

put those troubles once we're done with the Postal History Sunday post.

------------------------------------------

One of the fascinating things about postal history is that a single item can provide us with a window to view interesting events, people, or situations that occurred in the past. Sometimes, we are fortunate to find something that provides us with opportunities to go in all sorts of directions.

Starting to make sense of this cover

There is a lot to see and a fair amount to figure out with this particular item - which is just one reason it appeals to me. The hardest part is figuring out where to start. In my case, I started with the part I understood the best - the use of a 24 cent United States stamp to carry a letter from San Francisco, leaving July 31, 1865, to Liverpool, England.

The postage stamp at lower right, with the lilac coloration is the United States postage stamp. The cogwheel shaped cancellation was used in San Francisco during the 1860s, so that matches up nicely with the round marking at the lower right corner of the envelope that gives us the July 31st date from San Francisco. The postage rate at the time was 24 cents for a simple letter weighing no more than 1/2 ounce that left the United States for a destination in the United Kingdom. If you want to review that particular rate, this Postal History Sunday from January of 2021 will help.

That was the easy part, but what is it with all of those pink colored stamps - of which one is almost entirely under the 24 cent stamp?

The pink stamps are denominated as paying 2 and 1/2 pence of postage for the colony of British Columbia (north of Washington state in the US), which is now part of Canada. Prior to 1858, this area had been an "unorganized" British colonial territory known as New Caledonia, but with the gold rush in the Fraser Canyon and the corresponding influx of people, the area became a British colony.

So, the person who mailed this letter, paid for internal colonial mail services in British Columbia AND they paid for the United States postage to get the mail from San Francisco to Liverpool. All of this apparently paid with postage stamps - a statement that will not be entirely true as you'll see later.

That's enough to start with - and we'll get back to more details after a - hopefully interesting - interlude.

Getting from here to there

Williams

Creek was the site of much of the early successes during the Fraser

Canyon Gold Rush. Settlements such as Marysville, Richfield and

Barkerville sprang up to

gain varying levels of importance. Barkerville had a documented office

for Barnard's Express, a private company that carried mail, early in the

1860's and that's where I suspect the first Williams Creek post office

was established.

This item likely followed this route:

- Barkerville (Williams Creek) - July 21 to July 23 based on typical travel times

- carried by Barnard's Express on the Cariboo Road (you can see it on the map from Soda Creek to Ashcroft and Lytton)

- carried by Dietz and Nelson at Yale (another private carrier) to New Westminster on July 26

- Across the Strait of Georgia to Victoria, Vancouver Island

- Victoria to San Francisco via steamship

- Overland to New York - sometimes by train, some of the route by stagecoach.

- across the Atlantic Ocean on Cunard's Persia to Liverpool

The usual stage time from Yale to Barkerville (approx 380 miles) was four days. A special express, that included driving the coach during night hours, set a record at 30 hours - which is quite an accomplishment if you start looking more closely at the route these coaches would have to take to get from Williams Creek to New Westminster. It would not be unreasonable to expect letter mail to be sent on the express, so a July 23 send date is not out of the question.

Some of the material I

read suggested that this mail circuit was completed twice a week - so

departure from Williams Creek would have depended on that schedule.

The Cariboo Road

|

| Sketch map of the existing routes circa 1860 - signed R.C.Moody |

Prior to the gold rush, much of the travel in the region was accomplished via water routes and less developed trails The map shown above (you can view a larger version by clicking on it) is a sketch map of the region that likely reflects the state of transportation in 1860. Richard Clement Moody had accepted the post of Commissioner of Lands and Works and Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia (August 1858) and was also made Commander of a detachment of Royal Engineers. The sketch map shown above was signed off by him.

If you look closely, there are two routes that combine land and water travel to the North in the late 1850s. The western route starts at Harrison Lake and goes north to Lillooet. The Dietz and Nelson company maintained services along this route as well as service from Yale to New Westminster.

However, the development of a wagon road was not something that interested Moody as much as other projects. On the other hand, Governor James Douglas was adamant about development of proper routes of transportation.

In 1862 the Cariboo Gold Rush attracted 5,000 miners. On this occasion, Governor Douglas produced his plan for a major wagon road, 18 feet wide, to run 400 miles from Yale, beyond the river’s gorge northward to Quesnel, and eastward to Williams Creek. The Great North Road, to be built by Royal Engineers and civilian contractors, was to end the threat of American economic domination by making the Fraser River, despite its obstacles, the commercial and arterial highway of British Columbia. He hoped that the road could be extended to link British Columbia with Canada. “Who can foresee what the next ten years may bring forth,” he wrote in 1863, “an overland Telegraph, surely, and a Railroad on British Territory, probably, the whole way from the Gulf of Georgia to the Atlantic.” Quoted from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography on March 4, 2022

Part of the Great North Road referenced by Douglas was to become the Cariboo Road. It was this route that was favored by Barnard's Express to carry mail south from Barkerville.

|

| Cariboo Road along the Thompson River 1867, from wikimedia commons |

The construction of the Cariboo Road is considered to

be quite an accomplishment, requiring work in all sorts of terrain

(from swamps to sheer cliff faces). Building of the road was most

likely complete or very close to complete at the point the letter from

Williams Creek was mailed in July of 1865. The road was over 400 miles

in length and it effectively connected the Cariboo gold fields to the

rest of the colony.

If you view the map shown above, you can see the two alternative routes in the southern portion. The older route going through Douglas and Lillooet and the newer route through Yale and Lytton. The completed route in 1865 would not have gone through Lillooet at all. The first photo of the Cariboo Road shown above would have been taken north of Lytton (the Thompson River is just to the East of the road.

In the present day, there is a movement to restore portions of the Cariboo Road and to research the exact locations of the original roadbeds.

|

| Cariboo Road north of Yale circa 1880 from this Canada Parks site (viewed 3/11/22) |

Getting to the Cariboo Road

Competing

routes brought about competition for transportation services. And, the

competition was mostly in the portion of the route that got to the

Cariboo Road itself.

The

general rule of thumb is that land routes were normally faster than

water routes. This, of course, assumes the path of travel was developed

to allow fast stage travel. This might not be the best assumption in

rugged

areas such as those required for this trip. In fact even in later years

(1900s) the paved road that followed the Cariboo Road was considered

hazardous by some, with no guardrails to provide some sense of security

for travelers who might look down form the precipice. You can listen to a CBC archived broadcast that

includes interviews of people who remember driving automobiles on that

road and remembering how difficult even that could be.

Regardless, the development of land routes to speed travel had become very important in the Cariboo region simply because the British Columbian government wanted to be able to prevent the interests of the United States from overriding those of the colony. The road also provided an opportunity to maintain some control and collect some of the wealth that was being generated there.

The

advertisement shown in two parts here references the two routes in

competition. The western route is labeled as the Douglas to Lillooet to

Junction route. This is the same as the Lake Harrison route shown in

the sketch map. The Yale and Lytton Wagon Road would be the eastern

option. Already in 1863, as the Cariboo Road was under construction,

the shift had begun to favor the newer, shorter (and faster) route.

|

| From the Aug 8, 1863 British Columbian published in New Westminster |

Barnard's Express, Dietz & Nelson and the BX Ranch

At the time this letter was mailed (1865), the Dietz & Nelson company carried mails from Victoria to Yale and they also ran a route from Victoria to Lillooet via the western route. Starting in 1862 Barnard's Express carried the mail either from Yale or Lillooet to the gold fields in the north. In other words, it was Barnard's Express that carried the mail on the Cariboo Road.

Barnard's Express became the British Columbia Express Company and was often simply known as BX. In the winter of 1863, Barnard's added sleighs for winter transport. In 1864, they added a four horse, 14 passenger stage to the route. By the time we get to 1867, Barnard's was able to buy out the Dietz and Nelson express company and incorporate it into its own business. In 1868, Barnard purchased 400 horses as breeding stock and founded the BX Ranch that would supply the engines that made this enterprise go.

|

| Ad in the British Columbian (New Westminster) newspaper published Dec 12, 1866 |

An excellent history of BX can be found here at the Barnard's Village site. If you would like to learn more, this book by Ken Mather (Stagecoach North: A History of Barnard's Express) is available through the Royal BC Museum.

Not bad for a guy (Joseph Barnard) who bought a mule so he could put the mail on its back and lead it up the existing trails in 1861.

George

Dietz and Hugh Nelson purchased the Ballou Express in October of 1862

and came to an agreement with Barnard in 1863 to connect an express

line. They also made a connection with Wells Fargo in Victoria for mail

coming to or leaving from British Columbia. By December of 1867, Dietz

and Nelson decided they could not make money with this situation and

sold their interest to Barnard, who clearly made the most of it.

Williams Creek Gold Fields

The map below from Great Mining Camps of Canada

can give us an idea as to why some of the settlements developed where

they did. Places like Barkerville essentially appeared where the

density of staked claims

was higher. And, where claims clustered, services, such as the carriage

of mail, tended to follow.

Placer miners discovered the south end of the gold field in 1860 and all of the river and stream sites that would end up producing significant amounts of gold would be discovered the following year. Production would peak by 1863, but there is still active gold mining in the region even today.

|

| Barkerville 1863 from Great Mining Camps in Canada |

Placer mining focuses on looking for the target ore in sand or gravel, rather than attempting to find a vein of gold in solid rock. The simplest approach with the least equipment and investment would be to "pan" for gold, placing some of the sand or gravel mix into a shallow pan with water. Swirling the pan would separate the heavier gold from the sediment, which was washed out by the water.

The power of the river could be used by building sluice boxes. These provided the opportunity to process larger volumes of the raw material and separate the gold from sediment. If you would like to learn more, I suggest this U.S. National Park Service page that discusses placer mining.

Getting Back to the Postal History

I suppose it is about this point that I should bring you back to the piece of postal history that started all of this discussion about placer mining, horses, road building, and the beginnings of British Columbia. At the start I outlined the route this letter took, but I didn't necessarily show you the things that tell me about that route and the postage rates.

The first clue is the cancellation that can be found on the 2 1/2 penny stamps.

There is a blurred marking that is actually an oval with the number "10" in the center. If it were clearly struck, it would look like this:

This marking was known to have been applied in the Williams Creek post office (Barkerville most likely), which was established in June of 1864. That office was actually supplied with two postmarks - and neither of them provide the name of the location or a date. The second marking can be seen at the bottom left of the cover.

The

purpose of this mark is very clear - it indicated to postal clerks down

the line that the entire postage had been paid at their post office.

And, cutting right to the chase, the total amount paid was 1 shilling

and 9 pence. The 9 pence was paid by the pink British Columbian stamps

(which had been supplied to the Williams Creek post office) and one

shilling was paid in cash, which was indicated at top left.

The slash in markings like this separates the shillings from the pence, so this marking is stating that one shilling and no pence were paid towards the additional postage required. That additional postage represented the 24 US cents required to mail the letter from San Francisco to Liverpool.

As a quick review - or maybe this is new to you - 12 pence were equal to a shilling. Two US cents were equal to each British Columbian penny, so 12 pence (1 shilling) is equal to 24 US cents. The one shilling in cash paid for the 24 cent stamp that sits very nicely on this envelope. And, that 24 cent stamp was applied on the envelope in New Westminster, but it was not postmarked until it got to San Francisco.

This is one of those interesting practical solutions that were put into place just to get things done with the systems that were in place. The only way someone in the British colony of British Columbia was going to write home to the United Kingdom was going to be via the United States. And, in fact, any such piece of mail was going to go through either New Westminster or Victoria (on Vancouver Island). Both of those post offices maintained a supply of US stamps which they would apply when appropriate.

The other practical adjustment comes about with the pink postage stamps.

If you will recall, I told you these stamps had a denomination of 2 and 1/2 pence EACH. That's 7 and 1/2 pence in postage. But, a few paragraphs ago I just breezed a little factoid past you when I said that NINE pence in postage were paid by these stamps.

The internal postage rates had been increased as of June 20, 1864. The internal postage rate from the Cariboo Region to New Westminster was 6 pence per 1/2 ounce. In addition to that, there was a 3 penny foreign mail fee, for a total of 9 pence in internal postage required. The problem was - there weren't any 3 pence stamps printed and available at that time.

The solution? Sell the 2 1/2 pence stamps for three pence and just use them as if they were worth three pennies each.

Works for me - and it worked for them.

There were multiple periods where Williams Creek had to operate without stamps and this excellent article by Steve Walske tells that story. Mr. Walske is to be credited with providing many reference materials that gave me the tools I needed to read this cover, including this article that discusses the postage rates that applied during the gold rush period.

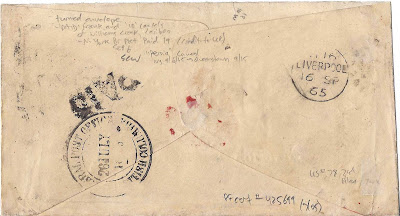

The back of the envelope features another "Paid" marking from Williams Creek and a larger, round marking that was applied at the "General Post Office" in New Westminster on July 26. Now you know how I had a date for its arrival at that location!

To the right is a Liverpool marking dated September 16, 1865. If we assume a July 24 send date, this letter took 53 days to make its way to the destination and it collected a whole host of storylines for us to explore for this Postal History Sunday.

--------------------------------

Thanks again for joining me this week. As you can probably guess, some entries take a bit more effort to put together than others. As always, the issue is how much detail is enough detail to accurately and correctly tell the story without getting bogged down in too much of the finer points.

For those who might like to learn more about any or all of the things covered here, take the links found in the text and/or check out some of the resources provided below.

Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come!

|

| Cariboo Road at Soda Creek |

Resources:

Walske, Steve, Stamp Shortages in the Cariboo Gold Country:

Mail from Williams Creek via San Francisco, 1864-1868, US Philatelic

Classics Society, The Chronicle, no. 218, vol 60, no 2, May 2008, pp

117-128

Walske, Steve, Postal Rates on Mail from British Columbia and Vancouver Island via the United States, 1858-1870, US Philatelic Classics Society, The Chronicle, no.212 ,vol 58,no 4, Nov 2006, pp 289-297

- Some excellent work here and the rate tables below come from this article.

British Columbia and Vancouver Island Rate Tables on Western Cover Society webpage

Forster, Dale, Paid, Unpaid, Collect and Free Markings on BC and VI Covers, Postal History Society of Canada Journal, No 107, Sep 2001, pp 49-57.

Wellburn, Gerald E, The Stamps and Postal History of Colonial Vancouver Island and British Columbia: 1849-1871, (1987).

- Since Wellburn's time, postal historians have been able to gain

access to more primary sources with far less effort. As a result, some

of the details in this "coffee-table" book are incorrect. Nonetheless,

an enjoyable book to view.

British Columbia and Vancouver Island Covers on Western Cover Society webpage

The BC Gold Rush Press

WAS a

blog that has dedicated itself to the history of the gold rush in this

area and provided interesting perspectives. It was still active Jan

2018, but the domain now appears to have been abandoned. If anyone

knows if this is still housed somewhere, let me know. This is why I

sometimes get very nervous about resource materials that are housed

primarily online, their volatility is high.

Downs, Art, Cariboo Gold Rush: the Stampede that Made BC, Heritage House, 1987

- This book is focusing on making the story entertaining but does

so with the integration of primary sources.

Brown and Ash, Great Mining Camps of Canada: the History and Geology of the Cariboo Goldfield, Barkerville and Wells, BC, Journal of the Geological Association of Canada, Vol 36, no 1 (2009).

- Lots of detail, well researched. The focus, of course, is on the

geological side of things, but the accompanying historical information

is also of use here. You may have to get past some terminology hurdles.

Some interesting maps can be found at University of Victoria's Digital Collection. Of note are carriage road maps (proposed in 1861).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.