Welcome to the 88th entry of the weekly Postal History Sunday writing

that appears on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. This is the place where I share a hobby I enjoy with anyone who

might have interest - whether it is a passing fancy or you get as

much enjoyment from postal history as I do.

Any hobby or

specialty can seem a bit ridiculous to those

who do not already appreciate it. Do you want to roll your eyes when

your second cousin, twice removed, wants to tell you ALL of the details

of their plans for deer hunting this fall - right down to layout of

the land around the deer-stand and the contents of the cooler full of

food they will take with them? Or maybe you have a younger brother who

will show your girlfriend every baseball card he owns on the weekend you

introduce her to the rest of the family.

Well, prepare to roll your eyes!

Ok. Ok. You can just not read this if you don't want to. Much more freedom here. And, I will also endeavor to keep it at least mildly interesting...

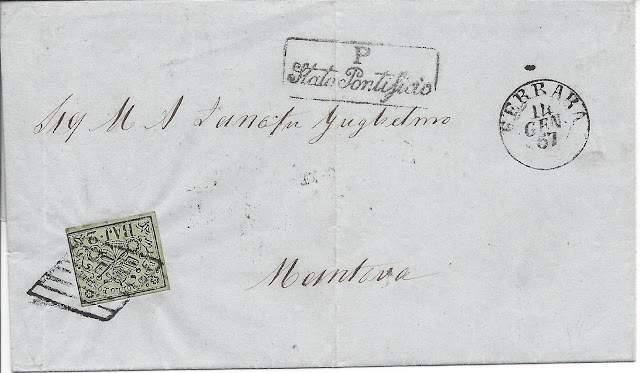

Here it is - an item that has been in my collection for a while that I think is REALLY cool.

Much of my collection consists of envelopes mailed in the 1860s from the United States to other countries. These envelopes show the use of the 24 cent postage stamp issued in 1861 to various destinations. And, yes - there it is! A 24 cent stamp at the top left of the envelope. Yay!

Now - an envelope sent to England using a 24 cent stamp at this time is NOT uncommon. After all, it cost 24 cents to send a letter to England from the US. So, you would be forgiven if you looked at this and said, "Yeah Rob. Looks like ALL the other ones you've shown me <roll of eyes>."

But, remember, you CAN escape if you want to. But, if you are curious as to why I like this particular envelope - read on!

Things you don't see all the time

One thing I appreciate about this item is the Detroit exchange marking. For those who don't remember, I discussed the purpose of exchange markings a couple of weeks ago (in case you are interested). For mail being sent from the United States to the United Kingdom in the 1860s, most exchange markings were applied at the New York foreign mail office (about 65% of known 24-cent covers). Another 18% are from Boston and 8% from Philadelphia. That leaves about 9% for the remaining offices. So, when I find a nice, clean marking for Detroit, Chicago or Portland - I tend to celebrate a little bit.

If you think about it, this actually makes a lot of sense. Most of the trans-Atlantic mail steamers (ships) left the port of New York. And, the majority of mail to other countries in the 1860s came from the states in the more populace northeastern states. Detroit, according to my research, accounts for between 1 and 2 percent of all 24 cent covers - which aligns with the mail traffic we could expect through that exchange office.

The 24-cent design of the 1861 series of US postage stamps is known for its range of colors (or shades). Stamp collectors try to acquire some of the most recognizable shades for their collection and they have names like red lilac, violet, lilac, gray, and steel blue. What you see is a "steel blue" shade of the 24-cent stamp, which is one of the colors people often seek as it is less common than most of the lilac and gray shades.

I focus on the postal history portion and I don't really

spend as much time on the colors of the different 24 cent stamps - but

that doesn't mean I can't be happy if I do happen to have a few of the

rarer stamp shades, right?

For those who might be curious, here are some representative examples of the different shades. Yes, I know, the difference is not always readily apparent. And, because the stamp ink used at the time was often highly fugitive, it means the color can change in appearance over time. But, that's something for another day.

One of the reasons we can be relatively certain that this particular stamp is a steel blue would be the December 1861 date of use for this cover. For the most part, steel blue stamps were used up by the time we get to the middle of 1862.

Anyway, the whole point here is that there is a reason for a philatelist (stamp collector) to be pleased with the cover because most pieces of postal history with a 24 cent stamp are NOT a steel blue shade.

But the real reason I think this cover is cool is....

Some

time ago, I showed this to an individual who looked at me, with a

puzzled frown, and asked me why someone would have a hand stamp that

would read "I Am Soap." I was a bit taken aback by that

because... well, I had already gone through the process of figuring out

what this thing said. Plus... I had a little help from others (thank

you Steve Taylor) to point me in the right direction. Imagine my surprise when someone else came to this conclusion in an online forum more recently!

I look at this now and chuckle about the "I am soap" marking every time.

If this postal marking were perfectly struck it would look something like this.

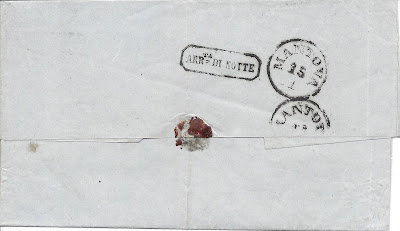

In my opinion, this cover becomes extra special because there is a story that can be told when we see that one partial marking on the envelope.

The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 ushered in the development of steamship services on the Great Lakes. By the time we get to 1862, when this letter was mailed, there were numerous steam services that carried passengers and cargo from port to port, including cities like Detroit. If you would like more information about the History of the Great Lakes, a book by J.B. Mansfield can provide plenty to dig in to. If you want an easier read, you can try this work by Theodore J Karamanski titled Great Lakes Navigation and Navigational Aides : A Historical Context. Or the History of Great Lakes Navigation by John W. Larson, which provided me with this excellent illustration of the water level differences that had to be dealt with as canals and channels were built to allow travel from lake to lake.

While this is all neat and interesting. Well, ok. I think it is neat and interesting. It's ok if you don't. I am more interested in the postal history aspect that goes along with the steamboat marking.Captains of Great Lakes steamers could be given a properly paid letter to be mailed at the post office once the boat had landed. This is not terribly unlike the service many modern hotels provide - accepting letters from their customers which they then pass on to the mail carrier when the mail carrier arrives.

The ship's captain and the ship itself were NOT

part of the US postal service, but they WERE entitled to compensation

for their services at this time. The captain (or his representative)

would take the letters given to them by passengers to the post office

(in this case, Detroit) and the post office would pay 2 cents per letter

to the captain of the ship for this service. The "Steamboat" marking

would be put on each letter received, which told the destination US post

office that they should collect 2 cents from the recipient to

compensate the post office for money they paid the ship's captain.

In

other words, the postage stamp for 24 cents did not cover the 2 cent

fee, it only covered the postage needed to mail something from the US to

England at the time. The postal service was 'out' the 2 cents until

the recipient of the letter paid the fee.

Now we have a problem. This letter LEFT the US postal service and was delivered in England. The British Post weren't going to collect 2 cents and return it to the United States as they had nothing in their postal agreement to do so! So, the postal service lost the 2 cents given to the captain for this letter.

You see, most of the old envelopes from this time period

that show a 'steamboat' marking like this one were mailed to a US

destination, not a foreign destination. I just happened to be able to

get an oddball that did not fit the mechanism to pay a ship's captain

for a service.

And there you are - reasons for you to roll your eyes and for me to be happy. What more could we ask for?

But wait! There's more!

Let me remind you of the front of this cover and let's look at the address panel:

J. Rule Daniell Esq, Polstrong near Camborne, Cornwall, England.

Since we have the ability to use various online map tools to help locate remote (to me) places of the world, I often like to do a little bit of searching just to see what I can find. In this case, I did not exactly find a town named "Polstrong" near Camborne in Cornwall - as I actually expected I would. Instead, I found that Polstrong was more of a house or land-holding that originates in the 1700s.

You

can find Polstrong Farm just to the right of center on the map above. This map was

part of a website that provides locations for houses and buildings in

England that have been classified as having some historical

significance. A few minutes looking at satellite images provides us

with a birds-eye view of current day Polstrong farm, which I show below.

I took note

of this because there are some high tunnels towards the center top of the image

shown below. Since we use high tunnels for some of our growing at the

Genuine Faux Farm, it makes sense that I might find this to be an interesting personal connection.

According

to House and Heritage, the Polstrong house was owned by John Rule

Daniell (1840-1911) in the 1860s, and he was part of the law firm

Daniell and Thomas in nearby Camborne. And, with a little searching, we

find evidence that J. Rule Daniell did apply to become an attorney in

1864.

If you look closely at the address on the envelope, you will see that it is addressed to J. Rule Daniell, Esq. The "Esq" (Esquire) part quite often referenced a person in the law profession. Since he would only have been 21 in 1861, we might be right in suggesting this was getting ahead of oneself a little. After all, we now have some evidence that he applied to be admitted as an attorney in 1864, a couple of years after this envelope was addressed and sent. But, there appears to be plenty of questionable use of that title, if the evidence of addresses on envelopes in the 1860s is enough to judge by.

Sadly, there are no contents in this envelope and we have no way of knowing who wrote this letter on a Great Lakes Steamship. It could have been a family member who was traveling in the United States and Canada. If their house and land was an indicator, the family had the money for travel.

But, take note. The letter was posted on December 5 in Detroit. Navigation on the Great Lakes typically began shutting down in December as the weather got colder and the water kind of became a bit "stiff" - making it difficult for steamships to go hither and yon!

You know, I've always wanted to say "hither and yon" in a Postal History Sunday. And you got to witness it today. Aren't you lucky?

This source (Statistics and Information Relative to the Trade of Buffalo), shows us that it was normal for the port at Buffalo to shut down in mid-December in the 1860s. Even if Detroit could stay open longer, there might not have been many other ports to go to much later in the month. I bring this up because it certainly calls into question whether someone was traveling for pleasure on the Great Lakes during this time of year. I am guessing we'll never know - but it sure is fun to speculate.

Thank you for joining me for Postal History Sunday. I hope you have a great day and a wonderful week to come!

.jpg)

.jpg)