Welcome! You've just stumbled upon (or intentionally visited) this week's entry of Postal History Sunday, hosted every week on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. Everyone is welcome to join me while I share things I learn as I explore a hobby I enjoy.

Let's take those troubles and set them aside for a time. In fact, let me suggest you pretend that those troubles are really important as you set them aside and make sure to tell the cat to leave them alone. I am fairly certain that any friendly feline will be bound and determined to sit on, sleep on, and play with them. They'll probably end up under the fridge, and you'll never see those worrisome things again.

This week on PHS, we're going to steal the title from an excellent baseball movie and use it to transport you back to the 1850s in southern Europe.

What you see presented here is a folded letter sheet that was mailed from Firenze (Florence), Tuscany (Italy) in 1855. At the time, Firenze was the capital of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (1569-1859, with a short break in the Napoleonic period). The destination for this letter was Rome, which was part of the Papal States.

If you would like a

moment to get yourself acquainted with the "lay of the land" during that

period, feel free to click on the map below for a larger image.

This cover qualifies as a letter to a foreign destination because Tuscany and the Papal States, while both in Italy and identifying as Italian, were not governed by the same entities. Each had their own postal services. They set their own postage rates, had different monetary units, and issued their own postage stamps.

Since we are talking about mail in the 1850s, it would make sense for us to ask what sort of postal treaty was in effect to determine how mail would be handled between Tuscany and the Papal States at the time. Typically, these agreements were bilateral in nature. But, it turns out that Austria and many of the Italian States shared an agreement that is often referred to as the Austro-Italian Postal League.

The Austro-Italian League

It

might be helpful to remember that Austria was the Austrian Empire under

Habsburg control (1804-1867) and encompassed a much broader area than

the current borders of that nation suggests. In addition to the regions

shown on the map below, the persons in power in the Italian states of

Modena, Parma and Tuscany were also part of the Habsburg line. Thus,

there was certainly an interest in keeping these connections strong by supporting efficient lines of communication.

If you view the map shown above, you might even notice that Austria laid claim to a significant portion of northern Italy, primarily the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia. All of this area operated under a Austria's internal mail system, even though some areas, like Lombardy-Venetia, were semi-autonomous.

But, when it came to mail between the Austrian Empire and Modena, Parma, and Tuscany, there would have to be a treaty outlining how mail would be exchanged. The interesting thing about the agreement that Austria pushed for was that the postal convention did more than arrange for mail between each of these states and the Austrian Empire - it actually included procedures for mail between each of these states as well. Thus making it a league of nations with a common mail exchange agreement.

Tuscany entered into the postal arrangement on April 1, 1851. Parma and Modena joined on June 1 of the following year (1852). And, interestingly enough, the Papal States, then covering central Italy, also agreed to exchange mail with Austria and these other states under this convention (Oct 1, 1852).

This league, along

with the German-Austrian Postal Union, were precursors to the global

mail agreement nations use today (the Universal Postal Union - since

1878).

How postage rates were calculated

Since the Austrian Empire was in the position of power, it should not be surprising that the rate structure followed their own internal rate structure. The required postage was determined by a combination of weight and distance traveled. The weight was determined by Austrian loth (effectively 17.5 grams) and the distance was measured by the Austrian meilen (or lega), with each meilen equal to about 7.5 km.

Rather than use more words, let me just illustrate how the rates worked with examples.

1. Distances up to 10 Austrian meilen

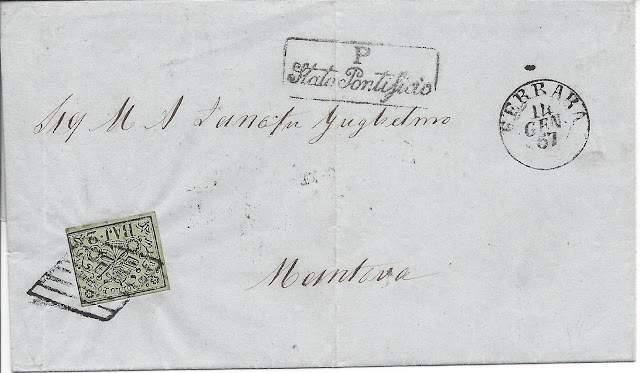

Above is a folded letter from Ferrara, then in the Papal States and on the border with the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia. Mantova, a city that we have actually featured in a previous Postal History Sunday, was considered to be within this first distance (even if current online map tools tell us it takes about 88 km to travel between the two).

This letter is a simple letter, meaning it did not weigh more than one Austrian loth. But, the Papal States did not use the loth as their weight of measurement, they used the Papal ounce, which was broken down into 24 denari - and one denari was 1.18 grams. According to the agreement, the Papal States would rate their letters per 15 denari, which actually was a bit heavier than the Austrian loth. But, what's a quarter gram among friends?

The postage required was 2 bajocchi per 15 denari - and a 2 baj postage stamp was applied to the bottom left of this cover.

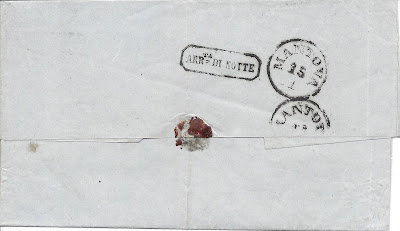

This folded letter was mailed in Ferrara on January 14 and received in Mantova (Mantua) on January 15.

This seems like a good time to remind everyone that the postal services of the time were often very sensitive regarding their reputation for timely service. As a result, we often see postal markings that attempt to explain what might be considered a delay of the mail.

In this case, it would not be unusual for something mailed in Ferrara to arrive at Mantova the same day. That means people in Mantova might actually get kind of upset if something from their friend or business partner did NOT arrive on the same day. However, this item must have been sent via a late mail train or coach. Hence, the letter arrived too late for a carrier delivery in Mantova on the 14th. The receiving post office in Mantova made certain to make that entirely clear by including this marking "ARRta DI NOTTE" (arrival at night) on the back.

This occurred at a time when many cities, such as Mantova, actually sent carriers out for multiple deliveries each day. People took rapid mail seriously in the 1850s!

Hey! They didn't have cell-phones. This was as close to texting as they could get.

2. distances over 10 meilen and no more than 20 meilen

Here is a letter that was mailed from Bologna, in the Papal States on July 9, 1857, to Mantova. This letter arrived on July 10 early enough to be delivered with the first distribution of the mail. However, unlike the first letter, there is no marking stating that this item arrived at night. Why? Well, it was perfectly normal for items traveling this distance to arrive the next day (and not the same day). So, there was no reason to provide a marking to explain a perceived delay.

The extra distance required more postage according the Austro-Italian agreement. Five bajocchi were required for every 15 denari for items that traveled over 10 meilen, but no more than 20 meilen. Sure enough, a 5 baj stamp was applied at the top left of this folded letter.

3. distances over 20 meilen

For

our last example from the Papal States, I offer up this item that was

mailed from Rome all the way to Vienna, Austria. Twenty meilen would

have been 150 km and the distance between Rome and Vienna is clearly

much greater than that (over 1000 km). The rate for mail for the

longest distances was 8 bajocchi per 15 denari - and an eight baj stamp

is applied at the top left to pay that postage for this letter.

Mail from other members of the union

The letter above was mailed form Vienna, Austria on August 20, 1858 to Florence (Firenze), Tuscany - arriving there on August 24. Like the last letter, this item definitely traveled more than 20 meilen to get to its destination, which means it required the highest rate per Austrian loth. In this case, it took 9 kreuzer in postage to pay for the service.

Below is a table that summarizes how postage was calculated.

| League member | < =10 meilen |

>10 and <=20 |

>20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria |

3 kreuzer |

6 kr |

9 rk |

| Lombardy-Venetia |

15 centesimi |

30 ctsm |

|

| Modena |

15 centesimi |

25 ctsm |

40 ctsm |

| Papal States |

2 bajocchi |

5 baj |

8 baj |

| Parma |

15 centesimi | 25 ctsm | 40 ctsm |

| Tuscany |

2 crazie |

4 cr |

6 cr |

There are actually FIVE different monetary units being shown in this table. Three are obvious with the Austrian kreuzer, Papal State bajocchi and Tuscan crazie. The centesimi in Lombardy-Venetia actually had a different value than the centesimi in Modena and Parma. Material I have read by a few different Italian postal historians indicate the difference by referring to the Austrian lira (Lombardy-Venetia) and the Italian lira (Parma and Modena).

I'll happily bow to whatever words they want to use as long as I can have a chance to keep things straight!

Back to where we started

It seems I have this tendency to show you a postal history item and then I go off on a tangent so that I can eventually come back to the original item. I hope that you find this to be either helpful or amusing rather than a constant irritant because - I doubt this is a habit that will go away any time soon!

Now that we have seen a postal table, I suspect most of us could - given a chance - figure out why there is a 6 crazie stamp placed at the top left of this folded letter from Florence, Tuscany, to Rome in the Papal States. The distance between the two is well over 20 meilen (150 km), so this would fall under the 6 crazie rate for distance. Tuscany's weight units were similar to the Papal States, so this would have weighed no more than 15 denari (17.75 grams).

The Tuscan postal service used this marking to indicate to the Papal States postal service that they considered the letter paid to the destination. In other words, this was an alert to the postal clerk in Rome that processed the letter as they took it out of the mailbag. The receiving postal clerk in Rome then proceeded to apply the dark diagonal slash of ink that starts at the bottom left and goes up to the middle of the envelope. This was how the Roman postal clerk marked the letter to show that they agreed that it was paid in full.

Now the postal carrier knew they did not have to collect any further postage from the recipient.

The other interesting thing about this particular piece of mail is shown below:

There are two slits in this letter. One is at the right and the image of that slit is enhanced so you can see it better in the image above. The other slit is just to the right of the "PD" marking. These slits were cut into the mail so that it could be fumigated or disinfected.

Tuscany had been suffering from the effects of the cholera pandemic in 1854 and 1855 and there was certainly much debate about the methods used for containing the disease. The science of the time had pretty much shown that disinfection of mail was not going to help, but governments wanted to be seen as doing something about the problem.

For those who might have interest, there is an interesting paper by Michael Stolberg that discusses the different lines of thought regarding the cholera outbreak in Tuscany at that time.

And, for those who would like to learn more about Italian postal history during this time period, I recommend Lire, Soldi, Crazie, Grana e Bajocchi by Mario Mentaschi. The book is written in Italian, but I understand a booklet with English text has since become available.

Thanks for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Have a great day and wonderful week to come!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.