Welcome to the May 1st edition of Postal History Sunday, featured weekly (hopefully not weakly) on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with this one (the most recent always shows up at the top). There is plenty there to read if you have interest as this is our 89th entry into the series.

As we approach the 100th PHS, I am hopeful that I can ask you for some input - but we'll get to that at the end of this blog. First, let's take a look at a folded letter from 1855.

Well, actually, this is a folded letter that has ANOTHER folded letter inside of it - which makes it doubly interesting.

First, let's read the cover

I

thought we could start by stepping through the process of reading the

cover. Remember, you can click on each image if you want to see a

larger version of the image.

There are three postage stamps from a series issued by the French in 1853, which tells us immediately that we should probably expect dates to land somewhere from 1853 to 1862, when the next series was issued. A total of 130 centimes of postage have been applied, so we should expect a postage rate that matches (hopefully).

The other thing to take note of is the number in the cancellation markings "1896." This is not a year date. Instead, the French post offices were each issued hand stamps to mark the stamps so they could not be easily re-used. Each post office was given a post office number, so hopefully this number will match up with the post office where this letter was mailed.

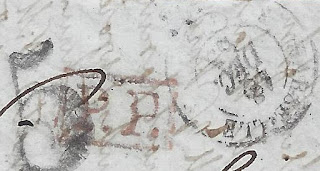

Then, there are a cluster of markings just underneath the stamps.

There is a black numeral "5" which is probably an indicator of an amount of postage due to be paid by the recipient. A red marking that looks like "P.P." that probably indicates at least some of the postage was prepaid by the sender of the letter. And, finally, a circular marking that shows that the letter was sent at the Marseille post office on Dec 18 (1855).

So,

the good news so far is that an 1855 date is good for stamps issued in

1853 AND the "1896" marking matches up with the Marseille post office's

number in 1855.

The back of the folded letter provides us with a few more markings. With these markings and the information on the front we can figure out the route this letter took:

- posted at Marseille on Dec 18

- took the train from Marseille to Lyon on Dec 18

- took the train from Lyon to Paris on Dec 19

- probably took the train from Paris to Calais on Dec 19

- crossed the channel to Britain

- took the British train system from London to Liverpool, probably getting there by the 20th

- boarded the Cunard Line ship Canada on Dec 22 in Liverpool

- this ship arrived in Boston on Jan 10

- the letter was taken out of the mail bag by a postal clerk in Boston on Jan 11

There is a docket at the top left of the front of this cover that reads "par Liverpool by the Canada Decbr 22nd." This makes it clear that the sender intended for this letter to be sent to Liverpool and be taken across the Atlantic on the Canada. But, the existence of a docket does not mean that the letter actually took the route indicated (though it usually did).

It's the Boston exchange office marking

that helps us to confirm that the letter actually took the route

indicated. The January 11th date lines up nicely with the recorded

arrival of the Canada on January 10 and the marking indicates

that this was a British Packet (Br Pkt). In other words, the sailing

ship was under contract with the British to carry mail across the

Atlantic. Happily, the Cunard Line was under just such a contract - so

this matches up nicely too!

Was the postage correct?

According to what we are reading on this cover, 130 centimes was prepaid by French postage stamps at the Marseille post office. There was a marking that read "P.P." which indicates that the required postage was paid to the border of the United States. This is markedly different from the "P.D." markings we have seen in many other Postal History Sunday entries. A P.D. marking tells us that the item was paid all the way to its destination. But, in this case, any postage needed to cover the mail costs in the United States was left unpaid.

That's where the black "5" on the front of the cover comes in. The recipient had to pay five US cents to cover the cost of the United States portion of the postage. The 130 French centimes covered the costs incurred by both the French and the British postal services. The French post office was responsible for compensating the British for their expenses as the letter traveled through England to get to Liverpool AND for the steamship that was under contract with them to cross the Atlantic.

The good news at this point is that these numbers actually match up with the postage rates for mail from France to the United States in 1855.

The French postage was 130 centimes per 7.5 grams from December 1, 1851 until December 31, 1856.

The US postage due for incoming foreign mail was 5 cents per 1/2 ounce (about 15 grams) during that same time period.

Things

would change in 1857 when the United States and France finally agreed

to a postal treaty that allowed persons in each country to send mail

fully prepaid to each other. If you would like to learn more about

that, you can check out this blog entry.

Two letters in one wrapper

The outer wrapper is addressed to G. Brewer, Esq of the Merriam, Brewer & Co in Boston. This makes this items stand out a bit for me. Why? Well, a typical address for business correspondence would not bother calling out the individual "G. Brewer Esq." It would simply have just given the company name and left it at that. So, already we have a hint that this may well have had content of a personal nature for G. Brewer.

Sure enough, as I checked the contents, I found two types

of paper with letters clearly written by two different persons. Now, I

have seen instances where a letter that did not belong with a cover had

somehow gotten mixed up and in the wrong place, so I decided to read and

see if I could determine if these both belonged together.

The letter on white paper was started on December 10th - and it rapidly became apparent that it was written by a young person to his siblings, who remained back in Boston.

The writer referred to himself as Gardy (based on his signature) and he addressed his letter to Carry and Nelly.

----------------------------

Dear Carry and Nelly

Since I last wrote I have had all of a sudden an outbreak of poison the same as I had at home which has kept me in the house several days and so I take the opportunity to write to you. And what do you think just in the middle of it who should call but Mr. Wales and he invited me to come and dine with them but as I had the poison I could not go out, neither could I go out to the Spragues on Thursday. But you may be sure that everybody was very kind to me and so the time passed very pleasantly on the whole. You don’t know what cold weather we have had of late. On last Wednesday there was ice so thick, the great wonder is that we have had no wind for at least a month.

December 11th

I must now tell you what Mr. Mayers sent in the Samson, first there are two wooden boxes and one cardboard full of preserved fruits. Then there is an old friend of yours, one of the tins in which the biscuits came has also been filled with preserved fruit, dates and brignolles. The dates I bought myself. There are two kinds you will not know, the name of the square green things are pieces of Pastegne as they call the watermelon here. The other is a little round yellow fruit with three stones in it called Azerrolle a kind of medlar(?) which I think you will find very good.

You will find less crystallized than glace fruit as the crystallized is less profitable.

December 13

I received Father’s and Calcutta’s(?) letters last night and am trying to guess what my New Year’s presents are. I will tell you a nice name for the little dog: “Zing a”.

The Miss Mayers are very much obliged to you for the music which we got yesterday but which they got (?). Miss Mayers have not had time to try. You know that the 20th is my birthday. Well Mr. Mayers has been kind enough to invite two French boys to come and spend the day with us so I shall have a nice time.

You asked me of what wood the bracelets are. Well they are made of cocoanut wood and made by the convicts at Toulon. Today George and I are going to spend on board the “Texas” where we expect to have a nice time thought it is very cold. I must not forget to ask you if you got the liqueur by the “Star Light” all safe as you do not speak of it in your letter.

December 18th

You know that in the first part of my letter I said that it was very cold but now it is too hot to put on my great coat. And now in conclusion I wish you Merry Christmas and a happy New Year. With best love to all. Your affectionate brother.

Gardy

------------------------

Well, the dates seem to match, but I was hoping the letter written on the blue-gray paper would confirm that young Gardy's letter had actually come under the same wrapper.

------------------------------

Marseille Tuesday Dec 18, 1855

My dear sir,

You will scarcely be surprised – Gardy having repeatedly been so affected – to learn that one morning during the week before - but on entering his room to call him I found his face considerably swollen. Inflamed and a slight (?) formed. He immediately on being made aware of it exclaimed “I am poisoned” describing the way (?) think he had been affected on former occasions (?). We kept him in bed that day and applied hot fomentatier? Finding on the following day that both the swelling and ? had increased. I thought it advisable to send for our medical man who treated the matter very slightly (?) prescribed certain drinks such as rice barley water, tisane, and ordered him to remain within doors for a week or 10 days and be careful in his diet.

The second day after he was so taken ? friend M. G. W Wales called and sat with Gardy in our drawing room for some time and he will have assured ? ‘ere this as I suppose that he did not fare very badly. He kept his bed for one day only and during the other 8 or 9 days that he stayed away from the college his spirits run so high that I can assure you we were somewhat relieved when he was able to go out again. He flew about the house at random.....

<more content not included in this blog>

signed by M. John Mayers (which you can see in the image above)

----------------------

And there it is! The confirmation we needed that these letters did, in fact, belong together. The events line up well and clearly the outer letter is written by the guardian in Marseille for young Gardy to Gardy's father, G Brewer.

Tracking down G. Brewer

Now that I had a glimpse into some of the personal lives of those who had a hand in writing these interesting letters, I had to do a little work to get some idea as to their story lines. My first success was in finding an 1852 advertisement that featured Merriam, Brewer & Company.

Apparently

the company were merchants that focused on the textile industry. This

gave me a little more leverage to determine that the addressee was

Gardner Brewer, which certainly matches up with his having a son who was

known as "Gardy." That left me with little doubt that the young person

writing the enclosed letter was probably named Gardner Brewer as well.

|

| image from Celebrate Boston site |

Merriam, Brewer & Co was apparently quite successful and Gardner Brewer was one of the wealthiest residents of Boston at the time. His affluence is reflected in the Brewer Fountain in the Boston Common. According to the Celebrate Boston site:

Gardner Brewer ... was born in Boston in 1800 (note, other sources site his birth year as 1806) and died in Newport, RI in 1874. He was one of the wealthiest and most liberal of Boston merchants. After attaining his maturity he was for some time a distiller, but afterward engaged in the dry-goods trade, and founded the house of Gardner Brewer & Co., which represented some of the largest mills in New England, and had branches in New York and Philadelphia.

In the dry-goods business ... he accumulated a fortune which, at his death, was estimated at several million dollars.

Mr. Brewer ... used his large wealth liberally for the public good, and shortly before his death gave to the city of Boston [this] beautiful fountain, which stands on an angle on Boston Common.

Brewer's home at 29 Beacon St was also something to behold and photographic records can be found here and here. So, clearly, not ALL of Brewer's wealth went to the "public good."

Another article by Aline Kaplan that focuses on the Brewer Fountain provided me with a bit more insight that helped me figure out the story line around these letters.

[T]he fountain ... was named for the man who paid for it and then donated it to the city of Boston. In 1855, Bostonian Gardner Brewer traveled to France to see the Exposition Universelle de Paris, a world’s fair. There, a fountain created by two French sculptors, Mathurin Moreau and Alexandre Lambert, caught his eye.

|

| The Palais d'Industrie in Paris from article by Arthur Chandler |

The world's fair in Paris ran from May 15 to November 15 in 1855. So, it does not seem too far fetched to conclude that Gardner Brewer brought his son with him during his travels to France. And, it was not all that uncommon for the children of the wealthy to study abroad, even if they were quite young. So, it is possible that Gardner Sr returned to Boston, while little Gardy stayed in France under the care of M. John Mayers.

I don't suppose we could figure out who M. John Mayers was?

I guess it should not surprise me too much that someone as affluent as Gardner Brewer would probably associate with others who were, in one way or another, prominent people for the time. This simply makes it more possible for me, 167 years later, to find various references to the people involved in this particular story line.

My first solid line on this individual came in the form of a paper by Amanda J. Haste, Ph.D., "The British Colony in Marseille: Meeting the Challenges of Migrant Life, 1850-1915."

Haste points out that the expansion of trade through Marseille led to

an increasing number of British "ex-pats" looking to create some of

their own community and safe-spaces in the city.

Marseille’s first chaplain, the Revd. Michael John Mayers (1850-64) ... lost no time in establishing a Sailors’ Home, or bethel. The traditional Bethel, or ‘House of God’ was a chapel, and sometimes a hostel, for sailors, and Mayers’ Marseille bethel provided everything the British sailor could need: food at cost price, and drink – but only tea, or an infusion of eucalyptus, because the bethels were strictly teetotal. The Sailors’ Home had rooms for conversation, for meetings, and for worship, as well as a library. Importantly, sailors could also rent accommodation at a very reasonable rate, thereby saving them from the bars and brothels.

Using money drummed up during a fundraising trip to the United States, the Revd. Mayers was able to open his Sailors’ Home in 1854.One has to wonder if, perhaps, the connection to Gardener Brewer may well have started during that same fundraising trip to the United States in the early 1850s.

Jean-Yves Carluer's blog provides us with even more context for the "House of Sailors" that was run by Rev Mayers, though Carluer points out that the day to day operations were managed by someone named Arthur Canney. But, it does become clear in this writing that Mayers had connections to a parent organization in New York City, a city where Brewer had a branch office.

If we recall Gardy's letter to his sisters, we will find that he mentions a chance to visit the Texas, likely a ship at the Marseille harbor. Mayers' connections to the sailing community probably made it easier for him to get his young charge a chance to visit some of the ships visiting the harbor.

Whatever became of young Gardy?

It appears that Gardy was only 13 years old at the time he wrote this letter to his older sisters Caroline (Carry) and Ellen (Nelly). Sadly, the "poison" that plagued young Gardner Brewer may have been a sign of a problem that medicine of the time could not repair and he died two years later, in 1857.

While

this may be a sad ending to this particular writing of the story, we

can still transport ourselves back to 1855 with young Gardy still

"flying about the house at random..." by reading his letter to his

sisters.

Thank you for reading Postal History Sunday! I hope you have a fine remainder of your day and wonderful week to come.

Celebrating the Journey to 100

I am fairly certain that the ONLY person counting the number of Postal History Sunday blog posts is me. But, since I have bothered to pay some attention to the count, it seems like it could add a little flavor if there were some participation as we approach the anticipated 100th Postal History Sunday.

Here is the plan (what, we need a plan?).

There are 3 ways you can participate (feel free to participate in more than one way if you wish):

- Ask Rob a question that he can attempt to answer.

- Send Rob a scan of a favorite postal history item and a couple of sentences about WHY this is a favorite item.

- Request that Rob write on a particular postal history topic.

I will feature these questions, favorite items and/or topics in Postal History Sunday as we approach 100. If you do not want me to share your name with your input, please tell me to omit that information if I choose to use your suggestion, question, or favorite item.

Questions and topic suggestions can come from people with any level of postal history knowledge. Prior questions I have received have included "Where do you find all of these neat things?", "How long would it usually take a ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean?", "How did you figure out the United States kept five cents and sent the remaining 19 cents to Britain?", among others.

Similarly, if you choose to share a

favorite item, it need not be old or super rare or really expensive. It

just needs to be a favorite item that is a piece of postal history.

Your reason for making it a favorite is enough!

And finally,

yes, I do reserve the right to decline to use submissions. After all, I

may not be willing or able to answer certain questions or cover

particular topics - I do have a full time job to do and have a farm to

run. But, let's all enter into this with an attitude of cooperation and

I bet this could turn out pretty well!

Keep up the great work, Rob. Your efforts are a wonderful example of the history beyond postal history in many old letters. Russ Ryle

ReplyDeleteThank you for the kind words Russ. I'll keep going as long as I am able.

DeleteI always enjoy reading you weekly. Keep up the good work

ReplyDeleteThank you Lyman. Comments like yours give me fuel to keep doing this. We'll see how long I can keep it up!

Delete