Welcome to the 4th entry of Postal History Sunday for 2023. PHS is hosted every week on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. Everyone is welcome here, regardless of the level of knowledge and expertise you might have in postal history.

One of the mistakes I sometimes make is I assume that because I wrote on something once before, I think I should not write on that topic once again. I call it a mistake because I am hopeful that my knowledge grows over time. If that's the case, revisiting something becomes an excellent to integrate new learning into what I had known before - and it's a fine way to recognize and address mistakes an errors.

I also need to remind myself that very few people have read, much less remember, every prior Postal History Sunday. In fact, some people may be joining us for the very first time! One of the keys to looking outward towards those who might be new is to be willing to revisit some of foundational concepts every so often. And, if you're clever, you just might through in new tidbits for those who are already comfortable with the topic.

Let's see how today's effort goes!

How did they know the postage was fully paid?

As you might guess, the answer to this question can have many different answers depending on the time and place in history. I enjoy the study of postal history in the 1850s through the 1870s - though I have been known to explore material from other eras. Today, I thought we'd look at some examples from the 1850s and 1860s in Europe.

The envelope shown above carried a letter from Rome to Paris in 1856. The cost of mailing such a letter was 20 bajocchi (20 baj per 6 denari : Oct 1, 1853 - Jun 30, 1860) and there were three stamps properly paying that postage applied to the front. That's great that I know the proper postage rate for this particular destination on that date (and now you do too!). But, how did the person who delivered this letter know that the recipient did not have to pay anything more?

Remember - at this point in time, you also had the option to send letters UNPAID with the expectation that the recipient would pay the postage. It really would be helpful if the carrier or clerk who delivered this item would not have to carry a big book of postage rates along with them to check to see if it was all taken care of!

In this case, I see the red box with the "P.D." and that tells me (and the carrier) that this item was "payée à destination," which translates to "paid to destination."

There is also a red circular marking applied in France. Red ink was often code that implied an item was paid and black ink was often indicated that postage was not fully paid. So, the first cover had a couple of clues for the postal carrier that no additional postage was due from the recipient.

I realize that it may be difficult to read what this marking says, so I thought I'd translate it here before we go to the next item:

E Pont - Pont-De-B. May 26 1856

The "E Pont" is a reference to the Papal States in Italy or Etats Pontificaux. At this time Catholic church maintained control over central Italy and are often referenced as either the Roman States or Papal States. They had their own postal services and had postal agreements with other nations, such as France. Pont de Beauvoisin (Pont-De-B) was the border town between France and Sardinia where this letter entered the French mails.

Envelopes were actually the exception, rather than the rule in the 1850s and 60s - and our first item was a small envelope. Our next item is an example of a folded lettersheet. An outer sheet was folded over the letter to provide a surface for addresses and postage while also protecting the contents from damage as it traveled through the mail systems.

This folded letter was mailed from Sardinia (which was in the process of unification with other Italian states) to England in 1860. Now that I have given you a clue as to what to look for, I suspect you can find the marking that told the receiving post office in England that the postage was properly paid.

Yes, it isn't in red ink this time - but it is the same thing - "payée à destination." In addition, there is a red circular marking below the P.D. that was applied in London. This marking has the word "Paid" in the bottom of the circle. This gave postal workers two clues for the destination post office in Market Weighton that all was well.

Countries had postal conventions where they agreed with each other HOW they would exchange mail. Not every country had an agreement with every other country, but there were usually sufficient agreements to get mail from most every here to nearly every other there on the planet in 1860. These agreements often dictated exactly how countries would indicate to each other that the item was properly paid or not. Many countries in Europe agreed on "P.D." as a standard signal that an item had no postage due and many used the color red for prepayment. But that was not always the case.

Slashes and x's

The next couple of examples are not quite items that were mailed from one country to another, but they illustrate some other ways an item was marked as 'paid.'

The item above was mailed in 1857 from Cento (near Bologna) to Rome. At the time, both of these cities were located in the Papal States of Italy, territory under the direction of the Vatican. The letter cost 6 bajocchi to go from Cento to Bologna to Rome and a green stamp was used to pay that postage. The post office in Cento used a blue handstamp with the town name (Cento) to mark the stamp to show that it was recognized as paying postage - and to prevent it from being reused in the future.

The Rome office, during the 1850s and 1860s, indicated that postage was paid by putting a long diagonal slash in ink on the face of the mailed item. It was quick. It was fairly efficient. And it served a purpose.

Now, when the clerk (or carrier) handed this item off to the recipient, they could quickly and easily see that nothing more was due on delivery.

Before we move on, some people reading this might be wondering how the postage was determined to be 6 bajocchi for this letter. I just so happens that the internal postage rates in the Papal States can not be quickly and simply described. So, if that particular subject interests you - try this Postal History Sunday where this cover makes another appearance.

And here is another Italian item that was sent from Modena to Mantua (Mantova). Mantua, during this period, liked to do a full "X" marking on items that had no additional postage owed. These "X" markings were normally big and bold - quite hard to miss! Unfortunately, I have noticed that prepaid letters to Mantua do not always display this marking, so a postal historian cannot rely on its presence to show that a letter was paid in full.

Postal History Sunday has actually featured Mantova a couple of times. The most recent was Return to Mantova in September last year. The first visit occurred in August of 2021, this older blog contains a bit more historical details for the city of Mantova if you like that sort of thing.

I am frequently amazed by the interesting themes and sub-themes that emerge as I explore the stories surrounding objects of postal history. Sometimes, I find that I am drawn, over and over, to particular locations - like Mantova. Each time I return, I learn a bit more, which is an excellent reward as far as I am concerned.

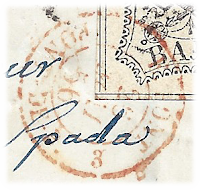

Franco means paid

The Dutch and Germans tended to prefer "franco" to "P.D." for linguistic reasons. This item was mailed in Rotterdam in 1866 and sent to Gladbach in Prussia (Germany). The Dutch post office combined the handstamp to 'cancel' the stamp with the marking to indicate that postage was paid. The boxed word "Franco" clearly defaces the stamp and is visible for the delivering clerk to see.

And, in some postal agreements, both countries were required to indicate that an item was fully paid. This item from Amsterdam to London (1865) has the "Franco" marking on the postage stamps (applied in Amsterdam) AND the word "Paid" in the London circular marking. As if that were not enough, the person who addressed this letter also wrote the word "paid" at the lower left. Or, perhaps, this was written by a postal clerk - but the writing style seems to be the same as the address. That helps me to be fairly confident that the sender wanted to emphasize the point.

And speaking of emphasis...

Sometimes, a person was pretty excited that something was fully paid. At the bottom left, the sender wrote “all paid! franco!!” I am not sure adding exclamation points make it any more likely that the postal people would notice it was paid enough - but I do hope at least one person who handled this item was a little bit amused.

For good measure, another exclamation mark appears at the top where the words "per Prussian closed mail" appears. I find myself wishing the contents were still with this envelope because the outside of the envelope sure makes it seem like the enclosure must have been exciting! (!!)

How many clues on this envelope from Faribault, Minnesota (US) to Oldenburg (Germany) can you find that told the delivering clerk that it was fully paid?

So, what would NOT paid look like?

This is a whole topic of its own, but I thought I should show at least one example.

Here is a letter that has a stamp on it, so it is possible that postage was paid. And, there are some red markings on the cover too. Hmmmmm.

The first clue that this item is NOT fully paid are the numerical markings on this letter. The red "40" is actually the amount to be collected from the recipient to pay for postage. Believe it or not, the black 'squiggle' to the right of the "40" is also a "4," which is the same amount due.

The second clue is that there is no "franco," "paid," or "P.D." anywhere to be found on this item.

The third clue is the red boxed marking that says "affranchissement insuffisant." This roughly translates to "insufficient postage."

In a very real way, postal history can be a bit of a puzzle - but it is an enjoyable one that begins to make more sense as you learn the language and the rules the postal workers used to communicate.

---------------

Thank you for joining me for this Postal History Sunday. I am always willing to accept constructive feedback and questions that will inform future "Postal History Sundays." You can give feedback using the contact form (which will send me an email) or by leaving a comment. If the comment form doesn't seem to be working, reload the page and that normally solves the problem.

Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Rob

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.