Welcome! You've managed to arrive at the proper place for the April

9, 2023 edition of Postal History Sunday. This is the place where I

afford myself the opportunity to share something I enjoy with those who

might have interest. It doesn't matter if you already love postal

history, or you are just idly curious. I'll do my best to make it

interesting and accessible to as wide of an audience as I can.

So,

put on your fuzzy slippers, find a comfy chair and get yourself a

favorite beverage. Take those troubles and hide them away for a time.

If you're lucky, you won't know how to find them again once we're done

here.

This

week's article starts in the year 1848 when the people of France

overthrew King Louis-Phillippe and elected Charles Louis Napoleon

Bonaparte president of the Second Republic. Following England's lead, postal reform that made postage more affordable

was among the early actions undertaken by this new government. And as

of January 1, 1849, France issued their first postage stamps to show

prepayment for these cheaper postal costs.

The postage stamps

depicted Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture, motherly love, and

fertility, reflecting the rural nature of much of the country. The top

of these adhesives were inscribed with the "Repub Franc" for République française.

The

folded letter shown at the beginning of this post bears an example of

the 20 centime stamp that was most commonly used to pay for a simple

letter destined for a domestic (in country or internal) destination.

This particular letter was sent by Gallien &

Toupet, bankers in Granville, France, to an individual in Lavaur,

France. The letter was mailed on June 23, 1850 and arrived at its

destination on June 26 after going through Paris on the 24th.

The cost of a simple letter in 1849

This letter represents a significant reduction in postage. Prior to

this point, the cost of a letter in France was a function of both weight

and the calculated distance traveled.* The distance from Granville to

Lavaur is about 840 km in distance, which would have required 1 franc (100 centimes) in

postage, five times the cost required to mail these letters under the

new rate structure.

This letter weighed no more than 7.5 grams and qualified for the 1st Rate Level (a simple letter) - 20 centimes in postage.

This rate was effective from January 1, 1849 to June 30, 1850 and followed this rate progression:

*note:

calculated distances were approximately equal to straight line

distances. A letter could take a less efficient route to get to its

destination and that did not add to the postage.

How did it get to where it was going?

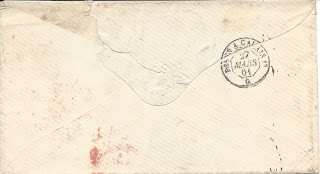

The

back of the folded letter includes a couple of circular postal markings

that

help us understand how it got from Granville to Lavaur. The marking on

the right was applied in Paris on June 24 and the marking on the left

shows the arrival in Lavaur as Jun 26.

The Paris postmark is a "transit mark"

because it shows us one of the intermediate points between the origin

and the destination. France usually processed mail and applied transit

markings when a letter was transferred to a new mail route. The Lavaur

postmark would be referred to as an "arrival mark" and provides

evidence as to when the postal clerk at the destination post office

processed the mail to be prepared for delivery or pick up.

The

map below can be enlarged if you click on the image. It provides you

with an idea as to where Granville (in the Manche

department, Normandy region) and Lavaur (in the Tarn department,

Pyrenees region) are, as well as their position relative to Paris. A

direct route between the origin and the destination would be

about 840 km. However, during the 1840s-60s, most mail would go through

Paris. That adds a little to the

overall distance traveled and shows how a calculated distance might be

different than the actual distance a letter was carried

At

the time this item was mailed, there was no railway line near

Granville. The closest rail would have been at Rouen. So, we can

assume that the letter traveled by coach to Rouen or to any point on the

rail line from

there to Mantes. The rail line terminated at Gare Montparnasse in Paris (known as Gare de l'Ouest - which translates to "Western Station"), which was the site for a well documented 1895 derailment.

While

that derailment has nothing to do with the cover I have shared, it

still adds a bit of interest. Both the train engine and coal tender

broke through the wall of the station and fell to the street below.

From Paris it is most likely that the letter rode the trains as far as it

could on the line through Orleans, taking the coach the rest of the way

to the destination, likely via Cleremont-Ferrand. A three day transit

for this distance where much of it was by horse-drawn carriage seems

quite reasonable.

The map below gives an outline of the

development of rail in France. With only a few exceptions, the focus of

the development was to create a "star" with Paris at the center. This

explains why many internal French letters during this time would have a

Paris transit mark.

What was in that letter?

I

am not terribly familiar with the banking forms of the time, however,

it looks like Mr. J Naraval of Lavaur had a balance to his favor of over

13,000 francs

in his account with Gallien & Toupet. The tally sheet at the left

appears to be withdrawals

or payments from the account, which are deducted from the prior balance

in the top right table.

Further down, there is confirmation of a deposit of 3382 francs to the account.

After

a cursory look, I did not find a contemporary reference for Mr.

Naraval. I did take note that the Gallien & Toupet firm could be

found in a bankers listing for 1870. After a little more searching, I

found images of other letters from this firm dated from 1847 to 1850.

Backing off of cheap postage a little in 1850

Our next item is a folded letter sent by V Pailhas, a

banker in Libourne, France, to a Mr Leurtault in Coutras,

France. The letter was mailed on March 6, 1852 and arrived at Coutras,

only 20 km away, on the next day (March 7).

The

reduction in postage rates introduced in 1849 just might have been a

bit too aggressive and France backtracked a bit with the new rates just a

year and a half later. The first rate (for a simple letter) was raised by 5 centimes and the

second by 10 centimes. Heavier letters remained the same cost.

This letter required 25 centimes in postage for the 1st Rate Level as it weighed no more than 7.5 grams.

A new 25 centime

blue Ceres stamp was issued in conjunction with the new rates and was

released on the same day the new rates were placed into effect,

replacing the black 20 centime value. This stamp also featured Ceres,

the Roman goddess of prosperity. This subject may well have been

chosen as a nod towards the agrarian economy which also avoided making any

particular political comment.

This postage rate was effective from July 1, 1850 to June 30, 1854 and followed this rate progression:

At

this time, there were different rates for local letters, but the price

of prepaid and unpaid letters remained the same. Later on, unpaid

letters would require a higher postage rate as the French postal

administration encouraged its patrons to move towards prepayment of

postage.

How did it get to where it was going?Libourne

and Coutras are only 20 km apart and are located to the northeast of

Bordeaux, in the department of Gironde. With that distance, it is

possible that this letter could have qualified for the local letter rate

for mail within the arrondissement. However, both settlements were

separated by a river, which marked the boundary between two

arrondissements - thus requiring the normal internal (domestic) rate structure to

be used.

The local rate would have been half the cost (10 centimes) if the letter qualified.

Coutras

is bounded by the Isle River to the South and the Dronne on the West.

The Isle flows into the Dordogne at Libourne. The map is dated for 1865, so the rail lines depicted were not active in

1852. However, many rail lines followed the the primary carriage roads that already existed in the

area - which can give us a good guess as to the carriage routes in 1852.

There

is a road noted from Libourne to S. Denis on this map and it does not

seem like a stretch to assume there was a bridge or ferry from S. Denis

to Coutras that would have served as the mail route.

As a historical aside - the Battle of Coutras was fought in this area during the 1587 religious wars. King Henry

III's edict that gave precedence to the Catholics and

prohibiting Protestantism in France resulted in unrest. This battle was won by the

Protestants (Huguenots), who were led by Henry of Navarre.

|

Depiction of Battle of Coutras by German painter and engraver Frans Hogenberg, wikimedia commons

|

The

representative of the crown, Anne de Bartenay de Joyeuse was killed

while attempting to surrender. At least one historian indicates that

this may have been in response to Joyeuse's history of executing

prisoners himself (Mattingly, Garrett (1959). The Armada. Houghton Mifflin Company).

What was in that letter?

The

sender, V Pailhas jeune in Libourne, was a banker who could provide the

service to buy bonds

for various enterprises in addition to standard banking services, such

as those provided by the recipients of the letter, Monsieur Leurtault

& Fils

(Leurtault & Son). They can be found on this 1858 list adverstising

the bond purchasing service:

Of interest to me is the use of "jeune"

after the name, which translates to "young." I have seen this a few

times in period literature and letters and I presume, perhaps

incorrectly, that this would be the equivalent to how we use "junior" to

indicate the younger individual in a father/son lineage where each has

the same given name.

As

I was digging for Monsieur Pailhas, I found a few other possibilities

that did not match the 1852 date. Is it possible that his son was a brewer/maltster in 1877 - or did he move on to another job? And is this his ancestor, getting into trouble in Libourne in 1793 during the first French revolution? Or this his father or grandfather in 1811, selling drapes and canvasses

in 1811? Given the consistent location in the Libourne area, it is not

at all unlikely that there is some relationship between these persons, even if it is not a direct lineage.

Maybe someday I'll figure it out. Or, I'll just leave at this and

someone else can solve the puzzle if it interests them.

Once

again, we have a standard ledger format that illustrated withdrawals

and acknowledgement of the receipt of money for the account. I wonder

how many people could figure out accounts in this fashion without the

help of computers in the present day?

The political winds blow and change French postage stamps

Louis

Napoleon III and the National Assembly disagreed with each other more

than they agreed. Napoleon III's response was to dissolve the sitting

National Assembly and replace it with members that supported his

policies and ambitions.

We can see this tide turning in France's

postage stamps of the time. In accordance with recently passed law

that required all postage stamps to bear his likeness, a new issue with

President Louis Napoleon's image was created in 1853. These stamps

still indicated that France was a republic with the “Repub Franc”

showing prominently at the top.

Our next postal history item is a folded letter sent by Foret pere

& fils, bankers, in Yssingeaux, France, to an individual in Bas,

France. The letter was mailed on Mar 30, 1853 and has a marked arrival

on March 31 at Monistrol, which is near Bas. All locations are in the

Haute Loire department of France.

What it cost to mail

The

1850 rate increments lasted for about four years (July 1, 1850 to June

30, 1854), so this item was mailed with the same rate table as our

second item.

This particular letter was heavier than 7.5 grams and weighed no more

than 15 grams (2nd rate level), therefore it required 50 centimes in postage.

Here is a reminder of the rate progression for the time:

How did it get there?This

is another case where the origin and destination are in the same department

(Haute Loire), so the distances are not great. You might notice that a

road runs from Yssingeaux to Monistrol, which identifies the most likely

route for the mail to travel.

Also

of interest for this item is the fact that there is no receiving

postmark for Bas, instead, there is a postmark for Monistrol. This is a

pretty good indicator that Bas did not have its own post office and was

serviced by the Monistrol office - making them both a part of the same

'arondissement' or postal district. To further clarify, if a person in

Monistrol wanted to send a letter to someone in Bas (or vice versa), it

would qualify for the local postage rate. But, this item started in

Yssingeaux, which was outside of that postal department, so it required

the normal internal letter mail rate.

What was in that letter?

At

present, this folded letter is only one sheet of paper, clearly not

enough to require the second rate level that was paid for by postage

stamps. This suggests that there were other enclosures that are no

longer with the item. It could have been individual receipts, money,

promotional material or reports. Or perhaps it held separate sheets reporting on

outgoing money / expenditures.

If you notice some notations in a

different hand, it

is possible that the information on other sheets were transferred here

at some point. I will never know for sure what caused the letter to be

heavier than 7.5 grams - but it can be interesting to consider the

possibilities.

Like so many surviving pieces of postal

history in Europe at this time, this is essentially another 'banking'

account ledger. It certainly makes sense that this is the type of mail

that might have a higher 'survivability rate' simply because these

documents were kept as part of the bookkeeping for individuals and

businesses.

Foret

pere & fils (father and son) focused on "recouvrements," or the

collection of money, on behalf of their clients. The list in this

ledger shows debts collected, including from whom, the location and the

amount. Or perhaps they show amounts to be collected.

It is

also noted at the top right that Foret pere & fils also dealt in

"escompte," which I presume would be the provision of a payment service

as opposed to a collection service on behalf of the client.

As a

postal historian, I can say I am grateful for this money transfer system. Without it,

there would be much less for me to collect and explore in postal history.

French Republic becomes French Empire

The

coup d'etat in December of 1851 allowed President Louis Napoleon III to

continue as president and replace members of the National Assembly with

those who would support him. This paved the road for a later

proclamation that

France was to become an empire under his leadership as emperor.

These actions were reflected in the postage stamps used to pay for mail service. In

1852, it was mandated that French postage stamps should depict Napoleon

III and the Ceres stamps were removed from circulation the following year. The heading at

the top of the stamp at that time still proclaimed that France was a republic (Repub

Franc). This time, the

stamps would be modified yet again, changing the "Repub" to "Empire."

Perhaps

you noticed already, but this new stamp had a denomination of 20

centimes. This new design was motivated both by political changes and

by a new postal rate structure. The new rates were effective on July 1,

1854 and would remain in effect for quite some time (Dec 31, 1861).

The

first major difference in these postage rates is the different cost for

prepaid mail versus unpaid mail. This was an effort to get postal

patrons to buy into the idea they needed to move away from a system that

collected money at the destination by making that option more

expensive. The postage rates for the first two levels returned to the

1849 amounts and the cost for heavier prepaid letters decreased.

If

it hadn't been clear before, it was now. The labor and time costs of

collecting postage from recipients (and the possibility that delivery

would be refused for an item) could be significant. On the other hand,

the French Post Office could provide cheap postage rates if mail was

correctly paid up front.

To

bring today's blog to its conclusion, here is a folded letter that was

mailed on March 5, 1859 in Nantes, France. The destination was a small

town outside of Brest which is now called Gouesnou. The address given

is "Goueznou pres Brest" or "Gouesnou near Brest."

The back of

this folded letter shows an arrival postmark at the Brest post office on

March 7. The lack of a postmark for Gouesnou tells us that there

probably was no post office in town. A rural carrier most likely

provided service in this case. However, I cannot state with complete

certainty that this is the case. Maybe that's something I can track

down and confirm at a later point in time.

And

here we are! By looking at some of the changes in postal rates and

stamp designs we were also able to look at the broader history of

France. Postal mail was a critical communication tool during this time

period, so it makes sense that it would reflect the politics,

technologies and economic realities of the time.

While that's

part of the reason why I find postal history and philately (the study of

postage stamps) to be fascinating subjects, this Postal History Sunday

illustrates other reasons. Each item can connect you to events that

occurred decades afterward (a derailment in Paris) or centuries before

(a battle in Coutras). If there are contents or if the addressee or

writer is someone of note, you can get a small snapshot of what their

lives must have been like.

A piece of postal history is

surrounded by stories - and as a postal historian, I can choose which

stories interest me each time I look at an item. I can explore each

story more deeply, or I can be satisfied with brief description. But,

in all cases, I have a chance to learn and explore - and I value these

opportunities.

Thank you for joining me this week for Postal

History Sunday. I hope you enjoyed some or all of this post. Perhaps

you even learned something new! Have a good remainder of your day and a

fine week to come.

-------------------------------

Postal History

Sunday is published each week at both the

Genuine Faux Farm blog and the

GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at

this location.