Welcome to the 140th edition of Postal History Sunday, a project I have undertaken to share something I enjoy with anyone who has interest. I attempt to write in a fashion that is accessible to a broad audience, including those who already appreciate this hobby as well as those who are simply a tiny bit curious about such things.

This week's entry was inspired by the folded letter written in 1854 that is shown below:

The letter is addressed to "Au tres Revd Mr. F Lhomme, Grand Vicaire et Sup. du Seminaire de Baltimore" which would be equivalent with "to the very Reverend Mister F Lhomme, Vicar General and Superior of the Seminary of Baltimore." The writing is crammed into every square inch of the paper that would not show on the exterior wrapper portion that included the address and postage. And interesting enough, the letter is written in a hand that is fairly easy to read in English, despite the address panel on the front being in French.

What is a folded letter?

I unfolded the letter so I could scan one side and give you an idea of what it looks like. When properly folded, the outside surfaces include the address panel and then two flaps that were sealed shut with a wax seal (the red area). This paper is actually folded one more time, making it too large for me to fit on the scanner. What you see above is actually about 7 inches wide by 10 inches tall. When fully unfolded, the paper is about 14" x 10".

Another surface can be seen below, illustrating how diligent the writer was in using the free space for content.

Envelopes are, of course, another form of "wrapper" that is used to keep personal correspondence - well - personal. They were not as widely used to send mail as the folded letter was in 1854. You can certainly see the attraction to not also having to have a pile of envelopes nearby in addition to the writing paper.

I suspect there might be some who could easily be confounded in trying to figure out how to properly write on and then fold a letter such as this one. In the present day, if you wanted some help with figuring out the folds, you could go to this short article at the Smithsonian's website or this one provided on the Library and Archives Preservation blog at Iowa State University's library.

Why do I suddenly have an urge to write a letter and try this out?

That's a bunch of stamps on that letter!

There are five postage stamps to pay the postage for this letter representing a total of 38 bajocchi (the currency in the Papal State in 1854). The postage paid was enough to get the letter to travel overland through Tuscany and Sardinia to France, then to England, and to pay for the British ship that would cross the Atlantic. However, once the letter touched the soil in the United States, US Post Office services were unpaid. So, the recipient would have to pay an additional 5 cents to receive the letter.

It turns out that the writer of the letter could not prepay ALL of the postage for a letter sent from Rome to the United States in 1854. There was no agreement to exchange mail between the two postal entities. That meant a series of OTHER agreements had to be used to get the letter from here to there.

In 1853, the Papal States and France signed a treaty that set a postal convention between them. The problem with that is that France and the United States did NOT have a postal agreement either. So, the French used their postal agreement with the United Kingdom to get their mail to the United States. But, none of this provided any arrangement for full prepayment for letters between Rome and the US.

Did you get that? It's all

as clear as mud, right? Rome used their agreement with France to access

France's agreement with the UK to get this letter to the border of the

United States. Simple? No. But, if it were simple it might not be so

interesting to study.

The French did sign a treaty with the United States in 1857 and a new convention with the Papal State in 1858. This provided an option to prepay the mail all the way to the destination between the US and Rome.

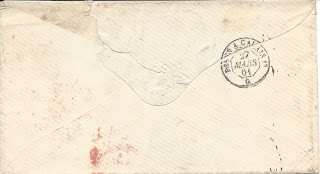

Here

is an example of the new 32 bajocchi rate for postage to the United

States that fully prepaid all the required postage. This letter was

mailed in 1861 and got to France by boat, rather than overland. At this

point in history, the Papal territory (and Pope Pius IX) was not

willing to work with the Kingdom of Italy, so mail had to go around,

rather than through the rest of Italy to get to France.

The other interesting thing to note is that this letter was mailed in an envelope. The pre-made envelope started gaining use in the 1840s, but by the 1860s it seems they were really taking hold, based on my own observations of surviving covers from that time. If you would like to read more about the movement from folded letters to envelopes, you might enjoy this article from the Smithsonian Magazine.

Now, let's move on to the social history that makes up another part of the story for our first letter.

Who was the Reverend F. Lhomme?

|

| image plate after p 58 in Memorial Volume... |

The Very Reverend Francois Lhomme (Nov 13, 1794 - Oct 27, 1860) had served as a Professor from 1827 to 1850 and then as the Superior at St Mary's Seminary of St Sulpice until his death. According to the Memorial Volume of the Centenary of St Mary's Seminary of Saint Sulpice 1791 - 1891, Lhomme served as the primary educator for the Greek language prior to becoming Superior in 1850.

Sulpicians were (and are) an order, originating in France, dedicated to the education of members of the Roman Catholic Church's priesthood. The French Revolution in the late 1700s was not friendly to the Catholics and many Sulpicians emigrated to the United States, forming the first US seminary, St Mary's in Baltimore. However, for the first fifty years of the seminary's existence, there were very few seeking training to become priests in the United States.

In order to be able to support the primary goal (educating priests), seminaries undertook to teach others who would not become priests to pay for their efforts to train new, "native" priests for the United States. Over the first 58 years, only 114 priests were trained and ordained at St Mary's. Father Lhomme's task was to separate the college from the seminary and during this time (until 1861) another 112 priests were ordained.

A few

clues about Lhomme's personality can be gleaned from the sources linked

in the first paragraph. It seems the man was "strict, but with a good

heart," a person who worked hard, was trusted, and was known for

"self-denial." The obituary notes that his health was declining in his

later years and he actually asked to be relieved from his post as

Superior more than once, but no replacement was forthcoming. I am sure

each of us can picture someone who has been in our lives at some time or

another that might be a Francois Lhomme. For me, at least, this makes

the man who received this letter a bit more real - rather some distant

individual with no features other than a name, title and a few dates.

Who wrote the letter?

|

| Francis Patrick Kenrick from this site |

The writer of the letter was Archbishop Francis Patrick Kenrick

(Dec 3, 1797 - Jul 8, 1863), who had become Archbishop for Baltimore in

1851. Prior to this, he had been Bishop in Philadelphia. Given the

amount of text crammed into this single letter, it should not surprise

us that Kenrick authored numerous volumes, including an English translation of the New Testament with annotation that was published in six volumes.

I get the feeling that Kenrick would make the volume of writing I have done seem modest by comparison.

At

the time this letter was being written, Kenrick was in Rome, by

invitation of Pope Pius IX, to discuss the definition of the Immaculate

Conception. I am not certain what this means, but you can read more if

you follow this link. Kenrick,

along with Michael O'Connor, of Pittsburgh, were involved in a meeting

from Nov 20 to 24, just prior to writing this letter to Lhomme. Some of

the content in this letter certainly reflected this meeting and the

ongoing discussion.

The root of the matter was this. Catholics in the United States were a minority, and sometimes under violent attack.

The perspectives of the Catholic clergy in the US was often vastly

different from those in Europe, where Catholicism enjoyed a privileged

status (though it was being challenged). Kenrick, Lhomme and others

were seeking new definitions that would allow the development of the

Catholic Church to progress in the New World. As it was, they already

had to bend the rules to offer educational services to persons other

than new clergy.

The letter begins by informing Lhomme that he may celebrate "the Purification," which I assume to be Candlemas (Feb 2) as a "revalidation of such dispensation." A dispensation is a relaxing of established rules. The letter continues to discuss such things as "mixed marriages" (Catholic and non-Catholic) and other topics that might require further dispensation from the Pope in order to help Catholicism to become relevant in a different society and culture.

As is often the case, the story can become far more complex and detailed if we want to dig further. I do not want to sell myself as being an expert in Catholicism or Catholic history, so I refer you to the links provided if you feel you want more.

Otherwise, I have granted myself a dispensation from perfection. Just this once.

Have a fine remainder of your day and a wonderful week to come!

---------------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.

Again, most enjoyable, my neighbor.

ReplyDeleteHello Rob - The relationship between France and the Papal State was very unique in Europe. In the beginning of the 19th century France and Austria fought against each other and at the end of 1815 the French finally lost the war and Austria took over some parts of Italy - some directly, othere due to the fact, that they appointed relatives of the Austrian ruling family. But the French stepped in early and kept the Papal State close to them, as they guaranteed the Pope´s safety with troops there. In the 1850s the Italians wanted the Austrians AND French out of their country and under Garibaldi a freedom-war started. The French, of course, helped the Italians vs. the Austrians and, after 1859 and 1866, moved them out of most parts of Italy. 1859 France and Sardinia changed territories, so the "Cote d´Azur" became French and other parts became Italian. A very good deal for the French, as we know today ...

ReplyDeleteThe Papal State shrinked, but was still existing in summer 1870, as on the 19th of July war between Prussia and the German States and France broke out. France was very optimistic to win this war, but a few weeks later they had to notice, that the war will be lost, if they don´t activate all their troops. So they transferred their French troops away from the Papal State back to France against the Germans and the Pope was without any military power vs. the "Italians". The Swiss Guard was only for ceremonial matters there and without any military value. So in September 1870 the Papal State ended and it all became the "New" Italy.

You show us collectors and postal historians very interesting, beautiful and instructive letters. Many of us appreciate this very much without leaving a comment, why so ever. Keep going, it´s always a great pleasure to watch and read, what you´ve bought.