Welcome to this week's Memorial weekend edition of Postal History Sunday. This particular holiday has its roots in an event that was initially called Decoration Day, which originated at the end of the United States Civil War. The first recognized widely celebrated Decoration Day was held in 1868 and by the late 1800s several states and cities had recognized the holiday. After World War I, Memorial Day was expanded to remember those who had fallen in all wars. If you would like to learn more, you can check this Public Broadcasting Systems page.

As I was growing up, Memorial Day was presented to me as a time to remember those who had passed before us, as well as those who had fallen as members of the armed forces. It was also a time to gather with family and partake of good food in a park. Over time, as Tammy and I became involved in teaching, Memorial Day weekend became dominated by college and high school graduation ceremonies. So now, we celebrate those who have successfully completed a stage of their lives even while we contemplate lives that were lived and have come to a close.

Shown above is a printed death announcement for Marie-Victor Chaverot, who died in Saint Alban, France, on June 12, 1865. The death notice was apparently printed on June 13 according to the printed notation at the bottom and the funeral itself was to be held on the morning of June 15th.

The content of the announcement is not all that different from what we might see in a modern obituary. The living relatives are listed at the beginning, requesting the recipient's attendance for the funeral ceremony of a 25-year old man who died of an undisclosed illness or injury. Unlike many obituaries, there are no details provided regarding the life of Marie-Victor. Instead, the focus is simply on the facts as they pertained to getting to and participating in the ceremony.

This item was mailed by folding the sheet of paper (a folded letter sheet) over on itself with the announcement in the center of the fold. Because this was pre-printed, it could qualify for reduced postage as long as the item was not sealed. And, sure enough, there is no evidence that any kind of wax or gummed seal had been applied. This allowed the postal clerks to inspect the contents to be sure no additional personal correspondence was included. As a result, the item only cost 10 centimes (instead of 20 centimes) to mail.

The instructions for attendance included a procession to the parish church of St Charles. The procession itself would travel down the Grande Rue de la Bourse in St Etienne, France. The map below is part of an 1877 engraving that was attributed to "Atlas National contenant La Geographie de la France et de ses colonies", by F. de La Brugere and Jules Trousset. Published in Paris by Artheme Fayard.

I was not able to uncover interesting information regarding the Chaverot family - which certainly could have been spelled in various other ways, making the trail harder to follow. On the other hand, I did find it interesting that the church itself was already deemed insufficient for the demand in St. Etienne. As early as 1828, there were plans to build a larger church nearby - I am guessing at the Place Marengo shown at the map. However, the new church was not constructed until the 1910s, eventually being given the designation of a cathedral in 1970.The black border had meaning

A prominent feature of our first folded letter that contained the death announcement for Marie-Victor Chaverot and the envelope shown above is a black border on the stationery. These borders can be found in varying widths and are normally printed in black ink. There are collectors who specialize in postal history items that feature this decoration and they refer to such items as mourning covers.

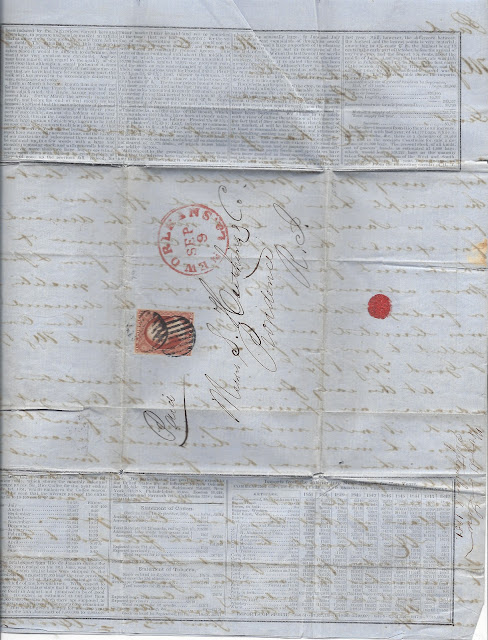

Shown above is an envelope that was mailed in 1867 from San Francisco, California to Edinburgh, Scotland (North Briton). The letter was posted on September 10, crossed overland to New York and then traveled over the Atlantic Ocean, arriving at Edinburgh on October 13, a little over one month after the date of mailing.

When we turn the envelope over, we can see that the black border actually includes the fold over and the flap. Clearly, this letter was not printed matter because there is evidence that the envelope was sealed. Our other clue is that the postage paid, 24 cents, would have covered the letter rate for mail from the U.S. to Scotland in 1867.

We can even zoom in and look at the area where the flap was torn to open the envelope. You might notice that there was an embossed design on the envelope flap that, unfortunately, did not survive the opening all that well.

Mourning was big business

A series of web pages that focus on the Victorian Era mourning rituals include a brief discussion on mourning stationery. It is here that author Alison Petch makes a statement that the width of the border might have something to do with the depth of mourning. "The closer relation the mourner was, the more mourning costume was prescribed and the longer the period of deep mourning." (Petch from this page) So, is it possible that these borders reflected the relationship of the sender to the deceased?

The envelope shown above was mailed from France to London, England in 1867. The 40 centime stamp properly paid the rate for a simple letter between the two nations. Apparently, George Blackwell did not have a permanent address at that time, so the letter was addressed to the "Post Office" where Mr. Blackwell would have had to go to pick up his mail.

In this case, the black band is certainly much thinner than our previous two items. Does that mean that the sender of this letter was not currently in "deep mourning?" Or was it simply the stationery design of choice? Perhaps others who have studied the protocols of mourning and sending notices would have a better guess than I do. But, it seems to me that you would use what you have - the width of the border is just what it was. I suppose one's adherence to protocol had a lot to do with one's affluence. If you didn't have the money, you didn't necessarily follow all of the protocol.

In the website previously mentioned, Petch suggests that "Victorian mourning costume has always been regarded in terms of gross

expenditure and elaborate etiquette, and, according to one source,

'snobbery, social climbing and profits of the mourning industry.' " Elsewhere, it is suggested that even people with modest means would save funds for proper funerals and mourning.

This time around, the back of the envelope did not carry the border around the edge of the flap. Instead, it stuck to the edge of the envelope on both the front and back. This envelope also has an embossed design - this time it is the monogram "A B." It seems logical to make the assumption that the monogram references a relative of George Blackwell's who sent the letter in the first place.

After a little digging, I found the Blackwell family papers in the Library of Congress and it is likely this envelope was sent by Anna Blackwell (1816-1900) to her youngest sibling, George W. Blackwell (1841-1912). One document written by Anna is datelined Paris in 1887 and it discusses the changing status of women in France. You can go to the bottom of page 10 and see the use of "a.b." to close a portion of the writing.

Apparently, Anna was a well known journalist and newspaper correspondent for forty-two years, based in Paris and, later, Triel, France.

Mourning covers saw the height of their use during the Victorian period (1837 to early 1900s) and they were part of the business of burying the dead. However, just because we see an envelope with a black border, qualifying that item as a mourning cover, it does not necessarily follow that the content was limited to a death announcement.

Certainly a death announcement might include additional news of family and friends, especially when the Atlantic Ocean separated the sender from the recipient (as it does in this case). We also need to remember that a person who was still observing a period of mourning might feel compelled to announce that fact by placing all correspondence in a mourning envelope until the mourning period was complete.

Often, like the envelope shown above, there are no contents enclosed, so we cannot say one way or another. We can only make the educated guess that it was likely some of the content was related to someone who had passed on.

Would you like to learn more?

If the topic of mourning covers is interesting to you, there is a Mourning Stamps and Covers Club that focuses on this very topic. If you take the link to that site, there are a couple of exhibits that display many additional examples of mourning stationery. There is also a book by Ernest Mosher titled "Mourning Covers: the Cultural and Postal History of Letters Edged in Black" that would be useful to those who would like to dive into the topic much more deeply than I have here.

And that seems like a decent place to stop for the day! I hope you enjoyed this week's entry. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

-------------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.