Welcome to this week's entry of Postal History Sunday. PHS is hosted every week on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. Everyone is welcome here, regardless of the level of knowledge and expertise you might have in postal history.

This week will be a bit different - but I think I say that almost every week. So, never mind that!

Just this past Wednesday I had the honor of giving a virtual presentation to the Collectors Club of New York. The title of the talk can be seen in the lead slide shown below. But, before I go much further, the video of this presentation

will be available for the next week and a half - until the next

installment of their Virtual Collectors Club Philatelic Program Series

is completed on February 15. After that point in time, the presentation

will be available to members only.

For today's Postal History Sunday, I thought it might be appreciated if I looked at a subset of the slides covered during this presentation. I have not taken the time to listen to the video - partly because I don't want to subject myself to... well... myself. But, you might enjoy the presentation. And, I can tell you that the written word and the spoken word can often convey different things - so it is worthwhile to do both.

The entire premise of this presentation was based on the interconnection of postal history in different geographical regions during the 1860s. My personal focus on postal history has been on items that include the 24-cent stamp of the 1861 United States postage issue. Most such items that have survived the past 160 or so years are folded letters or envelopes that were sent from the United States to foreign destinations - primarily to Europe. While it is possible to be quite knowledgeable about these items without much understanding of European mail systems of the time, I have found that learning about other postal systems has expanded my understanding and made the study much more enjoyable. In the end, I believe I have come to have a much deeper understanding AND I feel like it enables me to better to explain to others what I am seeing when I look at one of these covers.

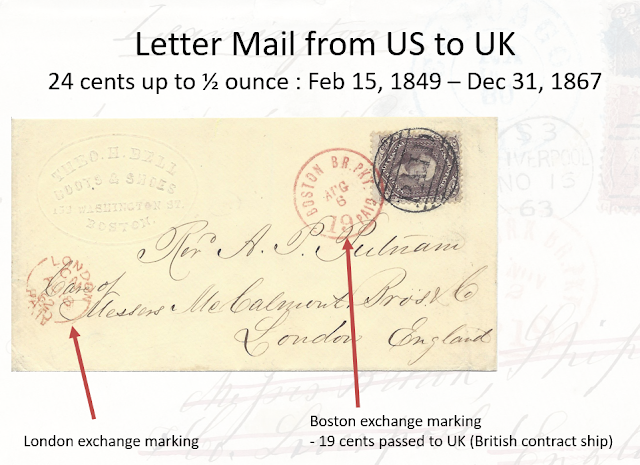

Let me start from the beginning by giving you two "baseline" items that will help us to understand two complex items.The twenty-four cent stamp was created primarily with the intent and purpose of making it easy for postal customers to pay for a simple letter mailed from anywhere in the United States to anywhere in the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and even the Channel Islands). When I speak of a simple letter, I am referring to the lightest weight class for an item that is classified as letter mail. The simple letter was the cheapest rate a person could mail a letter from point A to point B. In this case, the cost was 24 cents for a letter that weighed no more than 1/2 ounce.

A letter like this one would enter the mail at a local post office where it would often receive both a CDS (city-date stamp) and a cancellation marking. The cancellation would deface the postage stamp to prevent someone from using it again. The cover above originated in Boston and a black cancellation with the word "PAID" in it was used to mark the postage stamp.

If mail was destined for a foreign country, the letter would have to be sent to one of the post offices in the United States that was designated as an exchange post office for letters to the destination country. It just so happens that Boston was one such exchange office for mail to the United Kingdom. Other US exchange offices for the United Kingdom included New York, Portland (Maine), Philadelphia, Chicago and Detroit.*

The exchange office would apply an exchange marking that would include an indication as to whether the letter was considered paid and illustrate the amount of the postage that was to be sent to the destination country. In this case, 19 of the 24 cents were to be passed to the United Kingdom. Once the marking was applied, the letter was placed in a mailbag for its trip across the Atlantic Ocean. It would remain there until it arrived at the corresponding exchange office in the UK. In this case, it would be London. And, as you can see, the letter was taken out of the bag and the London post office applied their own exchange marking.

And that, my friends, is a baseline we can work from. We have an example of a typical letter from 1862 that traveled from the US to the UK. It is properly paid. It has a US exchange marking and a UK exchange marking. It is a basic, "nothing goofy going on here," example. It gives us a place to work from.

*

Baltimore was added later, but it and San Francisco typically only

received mail in the exchange office capacity during the 24 cent rate

period.

Since we have one baseline to work with, let's take a look at another baseline. Shown above is a typical letter from the 1860s that originated in the United Kingdom and was sent across the English Channel to France. A simple letter cost 4 pence and this letter could weigh no more than 1/4 ounce.

The concept of exchange offices still holds for letters between the UK and France. But, the markings don't look exactly the same as what we saw for the US/UK. There is still a mechanism to indicate to the receiving country that the postage had been paid. In this case, it is the red oval with the letters "PD," inside of it. In English, you could consider it as an abbreviation for Paid to Destination, while the French would be Paye a Destination.*

The back includes a London marking. Stephen T indicated to me that the square shape tells us the letter arrived in the London office too late to go on the last mail departure of the day. This makes sense since the London postmark is dated July 17 and the Calais marking is for the following day.

I guess, on the plus side, this letter got on the earliest boat and earliest scheduled trains the next day!

Most mail between these two countries were carried on contract steamships that traveled to Calais. Letter bags might be opened at the Calais office, but most were actually opened and processed on the train that traveled between Calais and Paris. These traveling post offices (or ambulant post offices) would have a marking with the letters "amb" prior to the name (Calais).

Another thing to take note of here is that the French were particular about where a letter came from. The letters "Angl" at the top of the entry transit marking indicated that the letter came from the United Kingdom (Angleterre - England).

In

France, when a letter boarded a new train, it would typically receive

another postmark on the back of the letter. You can see a French mobile

post office marking that reads Paris A Bordeaux. The ordering of the

names on this marking actually provides us with the direction the train

was moving (from Paris to Bordeaux). This makes sense since the letter

was ultimately destined for Bordeaux.

And there you go. Some

basics for mail during the 1860s from the United Kingdom to France. I

wonder what we'll do with all of that?

What we'll do is use that knowledge to help us figure out this thing!

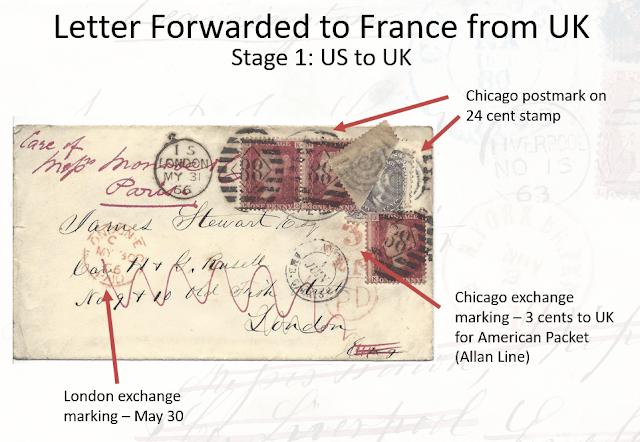

The envelope shown above was mailed in the Chicago in 1866. A 24-cent stamp was applied and properly cancelled. However, it (and the Chicago postmarks) were mostly covered up by a bunch of stamps from the United Kingdom. What's up with that?

Well, let's just start by trying to find the BASIC indicators of an item that was mailed from the United States to the United Kingdom.

- A CDS of the originating post office - Chicago - under the red postage stamps.

- A 24-cent stamp that pays the postage from the US to the UK

- A cancellation that defaces that 24-cent stamp (a target shape this time)

- An exchange mark from a US exchange office (Chicago - 3 Paid)

- An exchange mark from a UK exchange office (London)

It's all there! This is, of course, good news. This tells us that the letter took a normal journey for the time from Chicago to London. The postage was paid and the letter was treated as paid.

However, the

letter did not find James Stewart in London. The letter was sent care

of H&G Rusell* with the knowledge that Stewart was traveling.

H&G Rusell apparently knew that Mr. Stewart had moved on to Paris,

so they arranged to forward this letter on to his new location by

applying postage and remailing the letter.

Now we have to take our knowledge we gained from our second cover - the one from the United Kingdom to France - and see if there is evidence on this item that matches up!

Each of the red postage stamps are known as a "penny red," and each represented one penny of postage that was paid. Since there are four of them, we have four pence in postage paid. Let's go through the checklist:

- stamps to pay the 4 pence in postage

- a postmark (London) and cancellations to deface the stamps

- an exchange marking for the UK that shows the item is paid (PD in oval)

- a French entry marking - again the "Ambulant" Calais marking.

Once again, all of the components for a simple letter from the UK to France are there. The confusion is the fact that we have both the US to UK and the UK to France indicators all smashed together into one cover. It can feel even more confusing when you add the scribbles that cover the old London address and a second address in Paris at the top left.

You got all that?

You do?

Good, because I've got another for you!

If I were to cover up

all of the extraneous postal markings and show you this cover with only

the Boston exchange marking and the London exchange marking, you would

agree that this item is very similar to the first one.

If

you look very closely, you'll find a couple of smaller differences.

First, the date of the Boston marking is reversed (Aug 8 and 20 Feb).

The cancellation shapes are certainly different (no PAID in a grid for

our new cover). And, the London exchange mark is bigger and bolder.

But, the components all serve the same purposes.

This time, the letter was forwarded, but the postage was paid in cash, not postage stamps. A big, red "4" indicates the amount paid (four pence), which was the proper postage rate for a simple letter from the UK to France.

Once again, everything is there that we expect to be there.

As

you can guess, this particular item has even more to its story, so I am

going to send you to a couple of other Postal History Sundays if you

are inclined to read more.

They Went Thataway - if you would like a highly detailed look at this cover, this Postal History has that and more. You can even learn a bit about John Munroe & Co and General Bartlett. Sounds like a winner to me!

There and Back Again

- this one features a letter that went from the US to the UK and then

came BACK to the US. You can also learn a little bit more about the

Baring Brothers in that Postal History Sunday.

Wow! This has been quite a day for Postal History Sunday. Not only do you get a preview for a virtual presentation, you get direct bridges to not one, but TWO other Postal History Sundays from 2021 - just old enough that you might have forgotten about them! Or, perhaps you've never seen them before. Even better!

Thank you for joining me today. I hope you have a fine remainder of your day and a wonderful week to come!

Rob, Your talk was excellent - as is your decision to put part of it into writing.

ReplyDeleteI did have one thought on your talk/article that might have helped students to understand transatlantic mails and their markings. I would have mentioned near the start the three components that totalled 24 cents and very briefly stated what the 5/16/3 cents paid for.

Winston, thank you for the comment. I did debate doing just that. Part of me wanted to and the other part just wanted to get to linking the baseline items to the more complicated items. The latter part won out this time around. It's often a question of how much detail is useful and how much is distracting from the focus. Since breaking down the postage was not the focus of the talk, I went this direction with it all. Who knows which is the best? Still, I might go back and add that detail to the written version.

Delete