If you are new to Postal History Sunday, you are most welcome! If you are returning, you

know what to do! Grab a snack and a beverage and pull up your

favorite chair to join the rest of us. Maybe we'll learn something new together this week?

Oh - and before we get started, we need to take those worries and troubles and spread them on the bottoms of your shoes. Put those shoes on and walk around outside for a few minutes until you've successfully wiped them off and you can't recognize them anymore.

There - now we're ready!

The 1893 Columbian issue of postage stamps

Like so many collectors of United States stamps, I always held the 1893 issue that commemorated the landing of Columbus as something I would love to obtain a complete set of someday. This is a tall order because there are sixteen different stamps in the group and the last five have denominations of $1 through $5. That translates to a significant chunk of change if you want to collect a whole set. Why? Well, they don't cost a couple of dollars anymore - they can cost a whole lot of dollars!

The most common denomination is the 2 cent stamp. There were lots and LOTS of these printed and you can find pretty much as many of them as you would like if you wish without spending much money at all. And, if you would like to collect postal history with that stamp, you can do just fine on a limited budget.

For example, here is a fairly common piece of mail from Stoughton, Wisconsin to Madison mailed in the 1890s. I like it because we used to live in Madison and we had friends living in Stoughton. There's a personal connection which makes it a little more interesting for me.

I

have a long-standing goal to see if I can find a piece of postal

history showing each of the Columbian stamps that have a denomination

UNDER the $1 value. I suspect I won't allow myself to spend what it

would take to get those with $1 and up denominations - and I am okay

with that. The majority of the items with dollar values on cover

typically fail to

show payment of an actual postage rate. They were often mailed to or

from a collector who overpaid the postage needed - just to get a

postally used copy of that stamp. There's absolutely nothing wrong with

that, it just doesn't appeal to me enough to want to build up the funds

and then spend the money.

After all, there is enough of a challenge (and reward) finding the lower value stamps properly paying a postage rate as it is!

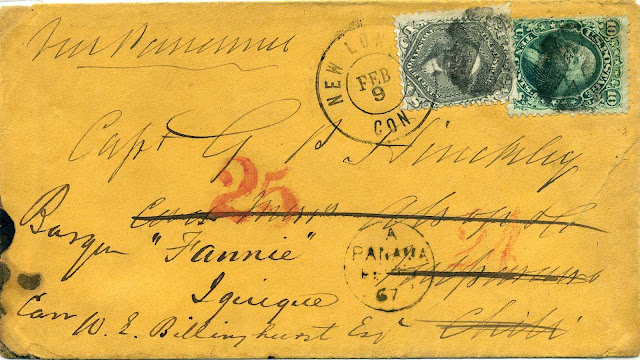

Along Comes the Otis Clapp & Son Correspondence

If

you are a postal historian, you recognize that we owe a debt to those

who kept all of their old envelopes and wrappers and we owe an equal

debt to the subsequent caretakers of this material who eventually

allowed someone to acquire them for collecting purposes rather than

burning them!

There are a fair number of items that were addressed to or sent from Otis Clapp & Son.

Most of the material appears to be the address and postage portions of

packages that were wrapped in the typical brown paper used for parcels

at that time.

Above

is a package front addressed to Otis Clapp & Son of Providence,

Rhode Island. Total postage is 45 cents, including a 30 cent and 6 cent

Columbian issue stamp. For those of you keeping track at home, the

Columbian denominations under one dollar were 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10,

15, 30 and 50 cents. So, I can cross off the 30 and the 6 from that

list!

Unfortunately, the mute cancels are smudged and unreadable if they had any words on them in the first place. And, since there is no return address on this package piece we cannot ascertain where it was mailed from, nor can we be absolutely certain as to the year it was mailed.

However, it is a fairly safe bet that this item was mailed in 1893 simply because the 1 cent and 2 cent issues are from the stamp series that was commonly found at post offices from 1890 to 1893. The stamps with most common use (such as these low value stamps) tend to make their appearance on postal history items closer to their dates of issue. If this package were mailed in 1895, for example, we would expect the designs of the 1 and 2 cent stamps to match a newer series of stamps issued in 1894.

Wait! You want to know what I mean by a "mute cancel?"

Let me remind you of this stamp:

The

oval cancel has city name "Boston" across the top. If you look at the

oval cancels on the package wrapper, you will see no indication as to

the town and there doesn't appear to be a date either. They have

nothing to say - hence they are mute. It's not my term, but it is the

one used in the hobby to indicate that no city or date is included in

the postal marking.

Internal Fourth-Class Mail 1879-1912

Since these are package fronts, we cannot be certain, but it is a good, educated guess, that the contents fit the definition of fourth-class mail. Essentially, anything that was not classified as first, second or third class mail fell into this final class of items that could be sent via the postal service. This included various merchandise, including the types of materials Otis Clapp and Son might ship out or receive.

The

rate was very simple - 1 cent for every ounce up to 4 pounds. And,

this postal rate was

effective from May 1, 1879 to December 31, 1912. Thus, the item above

would have weighed 45 ounces (2 lbs 13 oz) if we agree that it was a

fourth class mail item - which I think is an accurate conclusion.

A similar, third-class

mail rate was 1 cent for every 2 ounces and was applied to all types of

printed matter packages, such as books, circulars and newspapers. It

too, had a 4 pound limit, which eliminates it as a possibility for the

package front shown above (at this rate, it would have weighed over five pounds, which was not allowed by regulation).

The

item shown above is franked only by a 15-cent Columbus stamp and is

likely an example of a 15 ounce package mailed at the fourth-class

rate. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that this was printed

matter carried in a wrapper, making it a third-class

rate. We may never know for certain, and that's just the way things are

sometimes! But maybe we can figure out the most likely solution and accept that as good enough.

There are two options to describe this one:

- It was a catalog or some such printed item that weighed 30 ounces and was mailed as a third-class mail item.

- It was merchandise of some sort that weighed 15 ounces and was mailed at the fourth-class rate.

Thirty

ounces is a pretty hefty catalog for a specialized company like J.

Ellwood Lee and Co, so my conclusion is that this was also a fourth-class

mail item.

Unlike the first item, we have no other other clues to help

us determine a likely year of mailing. And, just like the first item, we

have no postmarks that will help us. However, a quick history of the J.

Ellwood Lee Company gives us an idea that, perhaps, we should not be

surprised if it was mailed somewhere in the 1893-1894 period.

J. Ellwood Lee Co

The J Ellwood Lee Company of Conshohockem, Pennsylvannia, (say that town name three times fast!) was a well-known supplier of medical supplies, such as rubber gloves, ligatures, rubber tubing, as well as other medical equipment.

John Ellwood Lee was born

in 1860 and started the business in the attic of his parents' home in

1883. By the time the Columbian Exposition came

around (the time when

the Columbian stamps were issued) in 1893 his company was quite well

established. J Ellwood Lee Company won five gold medals against

international competition at the fair. The company's involvement in the

exposition doesn't make it hard to see why Columbian issue stamps might

be on some of their mailings. A proud winner of five gold medals was

celebrating by using the stamps issued in conjunction with the

exposition to mail product. It seems unlikely that he would have

purchased so many stamps that they would be in use too many years after

1893.

This article on the Pennsylvania Heritage site can provide more detail on J Ellwood Lee if you find that interesting.

Oddly enough, Johnson & Johnson (yes, that Johnson & Johnson) purchased J. Ellwood Lee Company in 1905, placing Ellwood Lee onto its board of directors.

Supposing

this package held rubber tubing (not a bad guess giving Otis Clapp

& Son's activities), 15 ounces could have held a reasonable amount of

tubing. Below is an invoice that was on an online

auction site (image no longer available).

The

invoice shows an 1894 purchase of reels of silk - presumably used for

stitches. Given Otis Clapp & Son's focus as a pharmaceutical

business and the advertising on the front, I think it more likely that

the second package front carried some sort of rubber tubing - but it is still only a guess.

Antikamnia Chemical Company

Above is an item that bears 51 cents in postage to carry a package that must have weighed three pounds and three ounces of weight. Unlike the other two, this one was sent from Otis Clapp & Son to a customer in St Louis, Missouri, the Antikamnia Chemical Company.

Once again, we have a 1 cent stamp from the 1890-93 definitive issue that encourages me to believe that this, too, is an 1893-94 mailing.The Antikamnia Chemical Company (established 1890) was known for its powder and tablet products to reduce pain. The main ingredient, acetanilid, was sometimes mixed by this company with other active ingredients such as codeine, heroin and quinine. The initial efficacy of acetanilid rested on a single German study of 24 patients, but Antikamnia is known for prolific advertising to maintain sales of this product even after running afoul of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.

In his article, William Fiedler (see resources) states that "Antikamnia,

representing a therapeutically acceptable remedy for which many totally

unfounded claims were made, could well be called a 'pseudo-ethical

pharmaceutical.'" Fiedler's article does a fine job of outlining

the history of this company for those who have interest. The founders,

Frank Ruf and Louis Frost, both later laid claim to the ideas that

started the business and Frost was forced to sell his share of the

company in 1892.

The bookmark shown above is not in my possession and was found as

an offering on Etsy. An interested person could find numerous items

showing advertising by each company highlighted in today's Postal

History Sunday with a little looking.

Otis Clapp & Son

Otis Clapp first opened his retail homeopathic pharmacy in 1840 and the company Otis Clapp & Son was still operating until it was purchased in 2008. Oddly enough, you can find the company advertising various homeopathic remedies over a long span of time AND you can find it listed as a publishing company.

By all accounts, Otis was a remarkable individual, serving in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, is listed as a founder for M.I.T., the Boston Female Medical College and an orphanage.

Otis' son was also quite remarkable. Dr. J. Wilkinson Clapp was a professor of

pharmacy at the Boston University Medical School and put emphasis on

research. A decent outline of their history can be found at the Sue Young Histories site. Sadly, the old Otis Clapp company site with the company history has been taken down, so I can no longer reference it.

Apparently, Otis Clapp bottles are a fairly popular collectors item. These bottles were found on the Antiques Navigator site.

What I find interesting in all of this is the connections these three pieces of postal history make within the medical and pharmaceuticals fields. Clearly, Otis Clapp & Company was populated by exceptional people and the early stories surrounding that company are generally positive. Similarly, J Ellwood Lee was seen in a good light - even by employees well after he could have been excused from personal interaction with the workers. In both cases, the primary players saw significant success while being regarded as good and honorable individuals.

On the other hand, the founders of the Antikamnia Chemical Company

could be said to have found financial success, but there is some

question about the ethics and product quality that went along with it all. It

could be interesting to uncover how Clapp and Lee might have felt about

Antikamnia in the 1890s. Maybe that's a project for another day?

But, perhaps we should get back to the postal history stuff now?

Why the Ugly Cancellations?

The postal markings available to us on these parcel fronts are far from helpful to the postal historian. However, they did the job they were intended to do - deface the postage stamps so they could not be re-used.

Most third and fourth class mail items were struck with cancellation devices that did not include a date and sometimes did not even indicate a city/town of origin. In the fine book by Beecher and Wawrukiewicz (see resources), they suggest that these 'mute' cancels purposefully eliminated the date to not call attention to the speed of delivery of this type of mail.

We

need to remember that all sorts of things were being mailed in

fourth-class. Sometimes an item would simply have a mailing tag tied to

it. With all of the different sizes and shapes, shipping could provide

some interesting puzzles for the postal service. It is no wonder that

it might take longer and it is understandable that they did not want to

give customers any additional ammunition to complain about the speed of

delivery.

Not all of these cancels were perfectly mute -

often giving a town name. It is possible the markings on the items shown today had such text,

but I can't make it out if they did.

As far as the quality of the strikes are concerned, we can also surmise that the package surface was rarely as stable as a flat letter on a solid table top or mailing counter would be. It does not take much of an experience with a stamping device to figure out exactly how hard it is to get a clean strike on an unevenly supported surface.

Thank you for joining me this week. I hope you have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Resources:

H. Beecher and T. Wawrukiewicz, US Domestic Postal Rates, 1872-1999, 2nd ed. ( a newer, third edition to 2011 is now available)

Fiedler, William C. (1979). "Antikamnia: The Story of a Pseudo-ethical Pharmaceutical". Pharmacy in History. 21 (2): 59–72

-----------------------------------------------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.