Welcome to this week's Postal History Sunday, hosted on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog.

I'd like to recognize those of you who may be discovering Postal History

Sunday thanks to the publication of prior PHS blogs in the WE Expressions electronic journal or on the American Philatelic Society website. Thanks for stopping by!

Whether

you have been reading Postal History Sunday for some time now or if you

are just joining us, you are welcome. It does not matter if you don't

collect postal history or if you have much more experience in the area

than I do. Some who have been reading PHS for a while have informed me

that they do not intend to join the hobby, but they still like reading

these posts! Others with more expertise have kindly provided me with

more information and resources that I can use for future posts.

Whatever your background or motivation, put on your fuzzy slippers and get a favorite beverage (but keep it away from the paper collectibles!). I'll take a little time to share something I enjoy and, hopefully, we'll all learn something new in the process.

----------------------

Have you ever considered where all of the postal history comes from that people, like this farmer, collect? All of these old envelopes, folded letters and package fronts had to come from somewhere, didn't they?

Much of the postal history that I collect is available thanks to the willingness of individuals or businesses to maintain files and bundles of old correspondence and then allow them to become publicly available. Sometimes, family descendants are responsible for the dispersal or maybe the new owners of a business. Often, most or all of the contents are removed, and, frequently, these papers have been harvested for the stamps and the rest of the paper material is tossed.

And, we need

to remember - for every correspondence that is saved and placed in the

care of museums, schools, or individual collectors, there are countless

others that were simply destroyed.

A correspondence can have value for the postal historian because it provides a broad view of many postal systems, postage rates, and routes for the delivery of mail. By simply finding a few examples from a given correspondence, you can begin to get a feel for how mail worked at that time and place. For example, the Luden & van Geuns material can give us an idea of how business letter mail was handled in 1850s and 60s Europe.

There are other

times that a single correspondence provides us with almost ALL of the

examples of mail between two locations during a certain time in

history. We'll start with one such correspondence.

Jose Esteban Gomez Correspondence

Our

first example provides postal historians with examples of how the mail

worked between the United States and Spain in the 1860s. Because I do

focus on the 24-cent 1861 stamp (which you will see at the top right on

this folded letter), most of my focus has been on the items that have

that stamp.

To

my knowledge, there are just under twenty examples of the 24 cent stamp

on mail from the United States to Spain. Of those, only a couple do

not come from the series of postal items that were sent from Dutton

& Townsend in New York to Gomez in Cadiz. The postage cost for the

1868 folded business letter shown above was 22 cents per 1/2 ounce via

the British mail system and the 24 cent stamp overpays that amount. If

you want to learn more about Dutton & Townsend's willingness to

overpay on their letters, you can view Costs of Doing Business, which was a May, 2021, Postal History Sunday.

There

are, of course, other pieces of mail to Gomez in the 1860s that do not

bear a 24 cent stamp, and those were all sent by someone other than

Dutton & Townsend. By my informal count, there are approximately

another twenty or so items out in the world of collectors right now. It

seems likely there are more as I have not worked very hard to track all

of the Gomez items down. I mean... I do have a job and a farm to run,

you know!

The value of this series of business letters to a postal historian is in the way it illustrates the varied postal rates that could be used to accomplish the same end result - delivery of mail from the US to Senor Gomez. There was no agreement for the exchange of mail between the United States and Spain in the 1860s. Instead, a person could choose between one of several options.

The most common option was to send the letter via the "open mail" provision provided in the convention the United States had with the United Kingdom. Essentially, the sender had to pay for any postage required to get the letter into the hands of the British Mail system. The rest of the postage would be paid for by the recipient (Gomez).

This letter provides us with an uncommon rate - at least as far as surviving pieces of postal history are concerned. This 22 cent rate was only available starting in January of 1868 and was terminated in December of 1869. A person could still use the open mail provision during those two years, if they wished, but this 22 cent rate paid for the entire cost of postage and Gomez would not have been required to pay anything to receive it.

Elie Beatty Correspondence

Here is another item I have featured before. This cover initially appeared in By the Sheet that was published in April of 2021. If you are curious about some of the rate details, take the link to that blog.

The Hagerstown Bank correspondence has value for postal historians and those who study banking systems. Elie Beatty was a well-respected cashier and was apparently quite talented at his job. The site linked in the prior sentence gives us this summary:

"The historical significance of the collection lies primarily in the insights it offers to the operations of a prosperous regional bank during a tumultuous period in United States banking history. The antebellum decades witnessed a series of banking crises, most notably the Panics of 1819 and 1839, recurring recessions and depressions, and the famous "Bank Wars." The financial and political upheaval, combined with disastrous harvests during the 1830s, wreaked havoc on Washington County, Maryland, and caused the Williamsport Bank to suspend specie payments in 1839. Despite the prevailing economic climate, the Hagerstown Bank emerged as a stable financial institution with considerable holdings."

Elie Beatty's story can certainly be expanded upon, but I will suggest that you can take the link and read the summary there if you have interest. If there was a doubt as to Beatty's dedication to his job, I will add the following from the site linked above.

"Beatty resigned his position on April 23, 1859, citing "feeble health and the infirmities of age." Beatty died on May 5, 1859 at the age of eighty-three."

So much for retiring and traveling the world or doting on grandchildren...

Beatty covers are far more numerous than those in the Gomez correspondence and they cover a much wider time frame. As a result, collectors can find inexpensive examples that allow them to explore the postal rates and routes during the first half of the 1800s in the eastern United States. Most of the Beatty material you can find will exhibit the frequently used rates and routes. However, the fun comes when you start looking for as many different rate or route variations that you can find. There are some very uncommon postal rates that can be shown with a Beatty cover - if only you can find them!

Again, this is part of the

value of these larger collections of letters to the same recipient.

They give us perspective into what was the most common approach to using

mail services and what was exceptional.

Frederic Huth and Co Correspondence

Frederick Huth established this London banking company in 1809, which

eventually became a part of the British Overseas Bank in 1936. The Huth

correspondence has provided significant volumes of European postal history

examples for the 1800s - especially during the period prior to the use of postage stamps to prepay the cost of postage.

At

this time, postage was typically accumulative - meaning longer

distances required more postage. Also, each postal service that handled

a piece of mail wanted their fees paid, which could lead to some very

costly correspondence. This is one reason much of the surviving postal

history prior to the mid 1800s come from the affluent or business

concerns such as Huth's. It cost a great deal of money to send a

letter.

The letter shown above was sent collect to Huth &

Co and the postage fee of 2 shillings & 2 pence was collected in

London. The rate structure that was used to determine this postage

amount was in effect from July of 1812 to July 20, 1836. For

comparison, it cost only 6 pence to send a letter from London to any

part of Spain in 1868 (versus 26 pence in 1828).

This folded

business letter was mailed from Coruna, a coastal city in northwest

Spain in the Galicia region. The letter itself is dated May 3, 1828 and

a postal marking on the back tells us it got to London on May 28 of the

same year. Yes, that is over three weeks later - you counted correctly!

I will not try to pretend that I am an expert in European mail during the 1820s and I will admit to getting help figuring out the postage rate from other experts. Instead, I included this item to make a few points.

First, take a moment to click on the letter portion shown above and take note of the fine penmanship. And, the paper has a higher rag content, so it feels a bit softer and is far more resilient than modern papers. The condition of the item is amazing - especially considering its age. I added this to my collection because it was quite inexpensive and an extremely attractive looking piece of postal history (and I thought it might be a good Postal History Sunday subject).

In other words, it looks good and I am thrilled to be able to hold an item in my hands that was mailed in 1828!

Because

the Huth & Co correspondence was carefully maintained in their

files and then was eventually released to collectors, people like me can

affordably explore pieces of postal history that are nearly 200 years

old. If I wanted to, I could collect and learn all about many of the

postage rates and routes of the time, simply by finding and researching

letters that were a part of this correspondence.

Luden and van Geuns Correspondence

Like the Gomez correspondence, I have several items from the Luden & van Geuns correspondence. Unlike the Gomez material, the Luden & van Geuns material shows a broader range of postal origins. Below is a letter mailed from Branch Office Number 4 in Firenze (Florence) on Apr 28, 1868, arriving in Amsterdam on May 2.

This business letter shows an overpayment of the 50 centime rate. The route for this item is interesting since there were no completed rail service lines from Italy to the Netherlands via Switzerland. Rail service could take this item as far as Como (Italy) until it was placed on a Lake Como steamer on which it traveled to Colico. From there, it went by coach via the Splugen Pass to Chur. Swiss rail service took this item towards St Gallen where it likely crossed the Boden See on its way to Fredrichshaffen in Wurttemburg. From that point, this letter was able to travel by rail the rest of the way to Amsterdam.

I get the feeling I should have spent time putting together a route map on that one!

Johannes Luden was born in Amsterdam in 1792 to a family that had connections in the whaling business on his grandmother’s side. His father ran the firm Jb. H. Luden and Sons that was active in West Indies Dutch Colonial trade. I presume that Johannes may well have been involved in his father’s company before joining G. Nolthenius and Albert van Geuns in their own enterprise. Johannes Luden died in Amsterdam in January of 1868, so this letter arrived after his death, though the company kept his name.

The van Geuns family is an extremely well-known Mennonite family that was affluent and influential in the Netherlands during the 1700s and 1800s. Family papers are kept in the Utrecht archives that apparently go back as far as 1647, so further research on better known family members is certainly possible. Albert van Geuns was born in 1806 and, despite his status as founder of a bank, is overshadowed by numerous physicians, lawyers and ministers of note that can be found in the family tree. The family connections almost certainly must have provided significant capital to get a bank started.

Evidence that the financial house of Nolthenius, Luden and van Geuns was active as early as 1839 can be seen with the purchase of a new sailing frigate that was christened the Suzanna Christina. At some point after 1846, Nolthenius was removed from the name of the company and it appears Luden and van Geuns were active financiers until the early 1870’s.

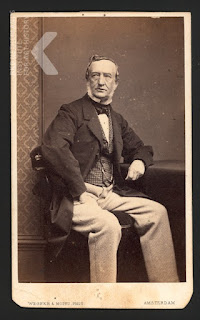

|

| van Geuns ca 1860 |

Luden and van Geuns were active bankers in Amsterdam at a time when the tides were turning against traditional Dutch power concentrations in the merchant houses. International banking businesses were changing towards less centralized structures and the old models struggled to stay relevant in the finance industry.

Luden and van Geuns may well have found themselves straddling both worlds, modeling themselves on traditional financial houses, but being part of a wave of new banking institutions. Unlike many newer banks of the time, they appeared to rely on family wealth (and thus limited investors) for their initial capital. Other banks spread out risk by having a larger number of investors, often allowing publicly traded shares. It seems that Luden and van Goens could not weather the trends or they could find no one to continue operations as its legacy did not carry on beyond the lives of its founders.

Nonetheless, their records included folded letters and envelopes that were mailed to them from all over the world. Most of these items illustrate fairly common rates and routes in Europe, but there are some items that are quite uncommon, including at least one letter from Brazil (and no, I don't have that sort of thing - sorry).

However, I have managed to find a few more letters addressed to Luden & van Geuns and wrote an article for the Postal History Journal in 2019 that focused on this subject. The article can be found in Issue No. 172 which can be downloaded for reading here.

If

you are not inclined to go download that article - or even if you are -

here is a second example from this correspondence. This folded letter

from 1870 originated in Paris, France and shows an 80 centime and 40

centime stamp paying the postage for a triple weight letter from France

to Holland. Other items in that article show different uses from Italy,

France, Prussia and Belgium.

------------------------------

Ah! Once again you have come to the end of a Postal History Sunday entry. Hopefully, you were so enthralled by it all that you were surprised that you made it to the end already. If that's the case - great! If not, we'll try to do better next time!

Thank you for joining me and letting me share something I enjoy. I hope you have a great remainder of your weekend and a fine week to come!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.