Welcome to the first Postal History Sunday after Thanksgiving 2024. The American Thanksgiving holiday has been, and continues to be, an important one to me. It reminds me to exercise my gratitude muscles in all things that I do, including the postal history hobby. So, let me take a moment and thank everyone who has taken a moment to read and enjoy Postal History Sunday, it is a privilege to be able to share what I can with you.

I am also grateful for those who have provided feedback to me. I received kind appreciation for my efforts while I attended Chicagopex last week. And, every so often, someone will leave a comment on the blog, or in social media, or in an email providing encouragement, additional information, and positive criticism. All of this helps me to feel the effort has value.

This week, we're going to provide more information about some recent Postal History Sundays. It never seems to fail - after I complete an entry and put it out "into the wild" for everyone to read, I discover something else that might have been good to include. Well, is this my blog or not? Since it is, I can certainly take the time to do a PHS entry that shares some of these things with you!

A Subtle Difference

On November 12th, Postal History Sunday featured letters mailed from the United States to Switzerland during the 1860s. The topic was certainly big enough that it made sense to gloss over a detail or three just so the main points weren't obscured.

But, there was one omission I felt sure that someone would bring to my attention. Then, much to my surprise, no one did.

|

| 35- cent per 1/2 rate via Prussian Closed Mail - to Andelfingen, Switzerland |

|

| 33-cent per 1/2 ounce rate via Prussian Closed Mail - to Ambri, Switzerland |

And this letter was mailed on July 30, 1866, arriving at its destination by mid-August. It is interesting to note that this letter was mailed just after the final battle of the Seven-Weeks War (Austro-Prussian War) on July 24 in the Grand Duchy of Baden.

And now I am going to ask the question I thought someone else might have asked:

| 1863 Cover to Andelfingen |

1866 Cover to Ambri |

|---|---|

These markings are called weiterfranco markings and they were used by members of the German-Austrian Postal Union (GAPU) to indicate that a certain amount of postage was to be "passed forward" to the next postal service. In both cases, the postage was fully paid by the person who sent the letter in the United States. The US sent 12 cents to Prussia to cover the expenses Prussia was responsible for. That included the amount of postage that was due to Switzerland!

So, these weiterfranco amounts represented the amount of postage, in German currency, that was supposed to be handed over to Switzerland for each letter. The kicker here is that the amounts for each letter is different.

The first letter has markings that read "f1" and "3"

The second letter has markings that read "f2" and "6"

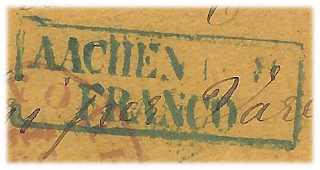

The first thing we need to know about these is that the members of GAPU used two different currencies. The Prussians and northern states would be passing silbergroschen and they would include the "f" before the amount to indicate it was a weiterFranco (paid amount forwarded). So, the "f1" and "f2" would indicate 1 silbergroschen and 2 silbergroschen. These markings were applied at the Aachen exchange office in Prussia.

The southern states used kruezer (3 kruezer for every 1 silbergroschen). So, the corresponding "3" and "6" refer to kruezers and were applied in Baden - likely on the train that carried the mail.

So, the first cover, mailed in 1863 at the 35 cents rate, was paid in full. The Prussians passed 1 silbergroschen on to Baden and then Baden passed the equivalent 3 kruezer on to Switzerland. The second cover, mailed in 1866, was mailed at the 33 cents rate and was alos paid in full. The Prussians passed 2 silbergroschen to Baden, which then passed 6 kruezer to the Swiss.

So, now the questions is... why?

The answer lies with the destination for each cover within Switzerland. At the time, Switzerland still had a distance component to their postal rates. In their agreement with the GAPU, there were two rayons (or regions). The amount of postage due to Switzerland was based on a rate of 1 silbergroschen (or 3 kruezer) per rayon for a simple letter. Our second letter was in the second rayon, so it required more postage to be paid to Switzerland.

If you would like to learn more about this, this Postal History Sunday looks more carefully at mail between Switzerland and the GAPU.

And, for those that are curious - the rate people in the United States paid to send a letter to Switzerland via the Prussian Closed Mails did NOT change, even if the letter went to the second rayon of Switzerland. This was simply how Switzerland and the GAPU accounted for letters exchanged between them.

More Humbuggery

On October 15th, I got to have some fun and write a bit about Humbugs and Dead Letter Mail. This 1865 letter was sent to the Dead Letter Office as either an "unclaimed" or an "unmailable" item. But, the postmaster wrote the word "Humbug" at the left. They were apparently aware that James E Dunnell was working some sort of scam that encouraged people to depart with their money.

In this case, the amount was $10.

I surmised that this might have been a lottery scam. But, guess what I found soon after writing that article?

This letter - which, unfortunately, does not have a corresponding cover (envelope or wrapper). It is a lithographed circular that is promoting a lottery with an entry fee of.... ten dollars.

This letter is from the "Office of Thos Boult & Co" who professed to be General Lottery Agents. In fact, they claimed to be "Licensed" by the government. And, even better for me and my story - this letter is dated March 21st, 1865. While it is certainly not directly related to my "Humbug" envelope, it is direct evidence showing that the lottery scams were quite active at that time.

The letter opens by recognizing that most states had laws against lotteries:

"Dear Sir, From what we can learn of Public Sentiment in your State, we are satisfied that there is among your People, a strong prejudice against dealing in Lotteries and feeling that this want of Confidence, cannot be removed until some person draws a good Prize."

Of course, like any "good" scam letter, they make certain to underline the last part to get the mark's attention. The idea being proposed is that the recipient can trust them to represent them for a lottery (thus getting around the law).

"... we offer you the chance of a Handsome Prize in a Certificate of a Package of Sixteenths of Tickets on the Grand Havana Plan Lottery to be drawn ... on the 30th day of April 1865."

Thus far, the letter has not quite gone so far as to promise a positive result. However, they do go on to illustrate how much there is to gain - with so little to lose.

"... no deception lies concealed under this communication; now as our object is to increase our Business among your Citizens; by putting you in the possession of a Handsome Prize; we offer you the above described Certificate with however this understanding that after we send you the money it draws, you are to inform your friends and acquaintances that you have drawn a Prize at our Office."Of course, the saying "thou doth protest too much" comes to mind. No, no! Of course, we don't intend to take your money and run. We just want to take your FRIENDS' money and run.

Now, they still won't promise that the mark is guaranteed a win, but...

"... if the Certificate does not draw you net at least $6000 we will send you another Certificate in one of our ever Lucky Extra Lotteries for nothing you perceive that you now have an opportunity to acquire a Handsome Prize; that may never again present itself; Improve it before it is too late, by sending your Order immediately..."

This letter seems to have everything. It tells us that we shouldn't delay and it even has it's "but wait, there's more!" moment. They'll send you another chance at a special lottery for free. It's a two for the price of one deal! And, of course, by the use of capital letters where they don't exactly belong and some judicious underlining they do a fine job of pointing us to the main issues of concern.

"To facilitate the prompt execution of our proposal use the enclosed envelope and make your remittance to our Office... Wafer or Seal your letter so that it will not come open in the Mails. Please consider this letter Strictly Private and Confidential, and send your order without delay"So, we come to the bottom of the letter. The very same people that are hoping to improve their business by having more people participate are now attempting to tell the mark that this correspondence is a secret.

And how much was the cost to enter to have the opportunity for a "Handsome Prize?"

Ten Dollars.

So, even if the envelope to James Dunning had nothing to do with this particular scam, there was likely no end to copy cats of this scheme. It really does seem like a good possibility that the envelope held money to enter an illegal lottery.

|

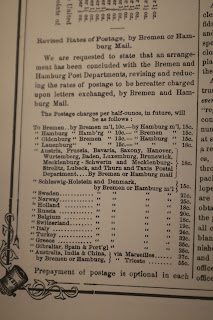

| from US Mail and Post Office Assistant |

The US Mail and Post Office Assistant was a monthly periodical that provided a wide range of material concerning the US Post Office and the mail during the 1860s. Lottery swindles show up periodically in this periodical, including the one described above for a "Wright, Gordon & Co." If you would like to read some of the detail, you can click on the image for a larger version.

This is where I realized that Jas. Dunnell may not have been the individual who was running the scam. Instead, someone who would claim to be their "agent" might have attempted to pick up the mail for this, potentially fictional, individual.

Perhaps the one person from this period of history you might think of when we talk about humbugs would be P.T. Barnum. And, as a matter of fact, Barnum wrote a book titled "The Humbugs of the World" that was published in 1866. In it, he reveals a wide range of scams, including the very lottery scheme outlined by this letter.

|

| P.T. Barnum 1851 - public domain image |

Barnum revealed that there were several "companies" that used the same scheme including Boult & Co, T Seymour & Co, Hammett & Co, and Egerton Brothers. And, while he ridiculed the scam itself, he had very little patience for those who sent them money either.

"Now, those who buy lottery tickets are very silly and credulous, or very lazy, or both. They want to get money without earning it. This foolish and vicious wish, however, betrays them into the hands of these lottery sharks. I wish that each of these poor foolish, greedy creatures could study on this set of letters awhile. Look at them. You see that the lithographed handwriting in all four is in the same hand. You observe that each of them incloses a printed hand-bill with “scheme,” all looking as like as so many peas. They refer, you see, to the same “Havana scheme,” the same “Shelby College Lottery,” the same “managers,” and the same place of drawing. Now, see what they say. Each knave tells his fool his only object is to put said fool in possession of a handsome prize, so that fool may run round and show the money, and rope in more fools."

Later on in the same chapter, Barnum outlines another lottery scheme that appeared in late 1864. This scam took the approach of telling the mark that they had a lottery ticket with their name on it that had already won, but since they hadn't purchased the ticket, they had to do something to collect their winnings.

“Your ticket has drawn a prize of $200,”—the letters all name the same amount—“but you didn’t pay for it; and therefore are not entitled to it. Now send me $10 and I will cheat the lottery-man by altering the post-mark of your letter so that the money shall seem to have been sent before the lottery was drawn. This forgery will enable me to get the $200, which I will send you.”

Barnum outlines clearly how the post office is often used for the lottery swindle. The perpetrator could mail a batch of circulars at any post office. And since they were printed (lithographed) they qualified for the cheaper postage rates. They could drop the circulars off at a post office and leave town. There would be no office or person there to whom it could be traced.

As far as payments, those too could be directed to some smaller post office where a relatively anonymous person could call for letters. And if the postmaster or others in the town started acting as if they were suspicious, they could simply leave the area and allow the rest to go to the Dead Letter Office. All the better to run the scam again some other day without being caught.

Mr. Meeker, I presume?

This envelope, mailed in 1936, was sent to a Mr. Lincoln V. Meeker. The address directs the letter to the ship at Port of Spain, Trinidad. However, when delivery was attempted, it was found that Mr. Meeker had "left the ship" and apparently no forwarding address was known. As a result, the letter was returned to Albany, New York.

The letter was sent via a Foreign Air Mail service to Trinidad at the cost of 20 cents per 1/2 ounce of weight. This airmail letter rate was effective from Jan 1, 1930 until Nov 30, 1937. For those who enjoy collecting US air mail, I believe this was carried on FAM route 6 from Miami. Those who know air mail far better than I can confirm or deny that bit of information.

The September 10 Postal History Sunday included this item as one of a few that I featured on that date. And, to be honest, I didn't give it too much space then. Since that time, I have identified someone who could possibly be our mysterious Mr. Lincoln V. Meeker - the person who left the ship called the Steel Navigator before he could receive this letter from Albany, New York.

|

| Lincoln V. Meeker (at left), Regional Director of Union Carbide Pan America 1967 |

I was able to locate someone with that name in a publication titled Revista das Classes Produtoras (Magazine of Production Classes), 1967\Ano XXIX N.991. The connection between Union Carbide (where this Lincoln V Meeker served as Regional Director Pan America) and the Steel Navigator is largely coincidental - but how many Lincoln V Meekers existed that allow us to draw those lines?

The Steel Navigator was a commercial steam ship for the Isthmian Line. This line of steamships were an outgrowth from the US Steel Corporation. It was not uncommon for companies, such as US Steel, to begin looking to acquire ships and building their own transportation service branch.

|

| cover - US Steel News, July 1936 |

The Union Carbide story has some parallel history in that, like US Steel, it was first incorporated in the early 1900s. Union Carbide's focus was on metal alloys early in its history. It is credited with a low carbon ferrochrome that was a precursor to stainless steel.

This is how we make a connection for Lincoln V. Meeker. Is it possible that he was a passenger on the Steel Navigator - and perhaps an employee of US Steel? His position with Union Carbide as the Pan America Regional Director gives us both a connection to related product lines and an area of the globe. It is possible that the intended recipient for this letter was a young Lincoln V. Meeker and, at the point this letter got to Trinidad, he had gone forward on another ship, a plane, or whatever, to another location.

Or maybe he jumped ship to Union Carbide from US Steel?

For now, this is all I've got to go on. Obviously, we can't yet draw any conclusions - it's all just a few facts that, with a lot of imagination, just might hold together. But, it's progress. Even if that progress turns out to have gone in the wrong direction.

And now, we find ourselves at a stopping point for this week's edition of Postal History Sunday. I hope you were entertained, at least a little bit. And maybe, just maybe, you learned something new.

-----------

Thank you for joining me today! Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.