Welcome to Postal History Sunday!

Everyone is welcome here, whether you know a lot or a little about postal history. Bring a little curiosity along for the ride, grab a favorite beverage and a snack, tuck those troubles away and put on the fuzzy slippers. This week, we're going to see what options a person in the United States had for sending mail to Switzerland from 1860 to 1867.

While those dates might seem somewhat arbitrary, I can provide a short justification. The start date is because I like studying postal history during this decade (the 1860s). The end date is derived from the point when significant changes in available rates were happening. It might be just as well to write a whole new blog entry starting in 1868 and ending in 1875 when the General Postal Union went into effect rather than try to cover all of that territory here!

Postal treaties set the rules for mail exchange

Letter mail between countries prior to the General Postal Union (1875) relied on postal conventions that were established by treaty between nations. Needless to say, not every pair of sovereign states had a direct agreement that dictated how mail would be exchanged. Mail between nations that did not have a direct agreement relied on a chain of postal conventions that connected them. In most cases, that chain was created by finding one intermediary that had independent agreements with both of the states in question.

Switzerland and the United States had no postal convention in place until 1868. This makes sense for several reasons, but the most obvious is that there was no way mail could be carried between the US and Switzerland without transiting a third nation. Any postal agreement between Switzerland and the United States would require connections to other agreements just to manage the transit through some or all of these independent states.

In 1860, the United States maintained postal agreements with the French, Prussian, Bremen and Hamburg systems. It was also possible to send mail to the British mail services to be sent on through whatever routes were available between the United Kingdom and Switzerland.

That's actually quite a few choices a person could make just to send a letter to one, smallish, country in the middle of Europe!

| Effective Date | Treaty Rate | Unit | Mail System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oct 1852 - Apr 1863 |

35 cents |

half ounce |

Prussian Closed Mail |

| May 1863 - Dec 1867 |

33 cents |

half ounce |

Prussian Closed Mail |

| Apr 1857 - Dec 1869 |

21 cents |

quarter ounce |

French Mail |

| Oct 1860 - Dec 1867* |

19 cents |

half ounce |

Bremen-Hamburg |

| Jul 1849 - Dec 1867** |

5 or 21 cents |

half ounce |

British Open |

| May 1863 - Dec 1867 |

28 cents |

half ounce |

PCM to border |

* The prior postage rate was 27 cents per half ounce (July 1857 - Sep 1860)

** This rate was advertised from Jul 1849 to Jun 1857, but still available afterward

If you look at the table shown above, you will find Prussian Closed Mail three times on the table. For the first part of the decade, the fully prepaid amount was 35 cents. But, in May 1863, the amount was reduced to 33 cents. And, you will see a third option at the end of the table where a person could pay the postage up to Switzerland's border, but no further, for 28 cents.

We will start with a letter that illustrates the 33 cent rate to Switzerland via Prussian Closed Mail.

|

| 33-cent per 1/2 ounce rate via Prussian Closed Mail |

The Prussian mail system provided mail services for the United States to

Switzerland starting in 1852 until December of 1867 when the Prussian

system was superseded by the North German Union mails (essentially the

Prussian mails with other German mail systems consolidated with it - a

topic all its own). The postage rate was reduced by 2 cents in May of 1863 in part as a response to the postal rate to Baden (a German State bordering Switzerland on the north) being reduced from 30 to 28 cents at the same time.

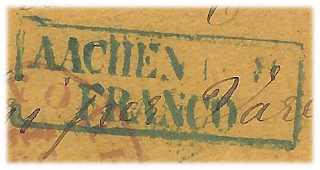

Mail to the Prussian system typically traveled through Belgium after a stop in England. Mailbags would enter the Prussian mail officially at Aachen (Aix la Chapelle) or on the mobile post office between Verviers and Coeln. This particular cover shows a boxed Aachen exchange marking that was applied once the letter was taken out of the mailbag.

|

| Aachen exchange mark |

This letter was put in the mailbag in New York City and remained there until Aachen, even though it did transit the United Kingdom and Belgium. This is why it was referred to as "Prussian Closed Mail." Despite carriage in territory not served by the Prussian mails, the intermediary postal services did nothing to process the individual mail pieces.

Both Belgium and Prussia featured highly advanced rail systems that facilitated rapid mail dispersal. Travel to Switzerland from Aachen required transit through Prussia and Baden or through Prussia, Hessian states, and Wurttemburg.

|

| "12" - marking applied in New York City |

Like many of the postal agreements at the time that involved the United States, a significant amount of effort was made to show how the postage was to be split between postal services. A letter sent at the 33-cent rate via Prussian Closed Mail to Switzerland required that the US send 12 cents to Prussia. This marking was applied using red ink, which was a message to the clerks in Aachen that the letter was considered fully paid and that the US owed Prussia twelve cents for this letter.

Some of the postage sent to Prussia was passed on to the Swiss for their costs to deliver the letter. Another piece of that postage went to pay the Belgians and British for transit through their territories. As for the 21 cents the United States kept, five cents paid for mail on US soil and 16 cents paid for the trip across the Atlantic Ocean.

|

| Baden railway marking - Z 23 is the train number |

Since I mentioned Baden earlier, this particular cover does a nice job of tying it all together. A significant number of the letters via Prussian Closed Mail to Switzerland from the US traveled through Baden. And, while Baden was part of the German Austrian Postal Union, they still maintained control of their mail system. So, they liked to process mail that went through their territory. A clerk on this particular train made sure to mark this letter to show that it had, in fact, gone through Baden on August 17 of 1866.

A 35 cent rate example

That brings us to a second envelope that was mailed to Swtizerland via the Prussian Closed Mail. This time, I get to show you a pretty cover with a 24-cent 1861 stamp on it. The letter itself was sent from the Swiss Consulate in Philadelphia (the docket at the top right tells us this information).

|

| 35- cent per 1/2 rate via Prussian Closed Mail |

This letter is particularly interesting to me because it was mailed on April 27, 1863, just days before the postal rate was going to change to 33 cents. In fact, by the time it arrived in Aachen on May 12, the rate had changed.

|

| Baden railway marking |

On the reverse of this particular cover is a different type of railway marking for the Baden "Eisenbahn." So, once again, a letter to Switzerland from the US took the route through this particular German State.

And one that was paid to the border only

Our next item was mailed in 1866 and it only has 28 cents of postage, which means it could only be paid up to the border between the German States and Switzerland. This letter also exhibits the boxed Aachen marking and it traveled on a Baden railway before entering at Basel, Switzerland.

|

| 28 cents paid only to the border of Switzerland |

The Prussian system is interesting in that it would allow mail from the United States to be paid 'up to the outgoing border.' In other words, the sender could opt to pay the 28 cent rate to get a mail item to anywhere within the German-Austrian Postal Union (GAPU). Once it reached the border, it would be sent on - essentially as an unpaid piece of mail from the Prussian system to its destination in Switzerland.

This rate was not advertised in the postal rate tables at the time, so the clerks or patrons had to be aware of other options that were not shown in those tables.

Since the letter was not fully paid to the destination, the recipient was required to pay 10 rappen (or centimes) in Swiss postage for the

privilege of receiving their mail. This Postal History Sunday

illustrates a situation where some mail was sent from Switzerland to Rome and the postage was split. So, this was certainly not unknown at the time.

|

| Double the 21 cent French Mail rate from the United States to Switzerland |

The French mail system provided the United States with services to Switzerland from April of 1857 until December of 1869 at a cost of 21 cents per quarter ounce (7.5 grams) for letter mail. Much of this postal convention can be viewed here if you are curious.

Mail to Switzerland via France would travel by trans-Atlantic steamship from New York, Boston, Portland (Maine) and Quebec bound for locations in England, France and Germany, depending on which steamship line carried the piece of mail in question. Items bound for France would typically sail directly to France or travel via Britain. The entry point in France was most often Calais (or the rail line from Calais to Paris), but it could also be locations such as Havre and Brest. If you would like more detail on how mail got to France during this period, this post will provide you will provide you with that information.

|

| border region of France and Switzerland |

The rail systems in France were developing rapidly from the 1840s through the 1860s and, for most of the 1860s, foreign mail was carried by train to Switzerland via three primary border crossings. There were other crossings that typically handled local mail and were unlikely to carry foreign mail, though it is technically possible.

Mail could enter Switzerland in the north at Basel, west at Pontarlier and south at Geneva. The route was chosen based on a combination of train schedules and location of the destination relative to the border crossing. The hope was to send the mail via the route that would see the quickest delivery time.

|

The envelope shown above is presumed to have gone via Pontarlier based on some incomplete train schedule data that I have located. It is entirely possible that this is incorrect and I hope to be able to decipher the route more fully in the future. The 1864 year date makes it possible that the entry was in the south at Geneva depending on the completion dates of some of the rail lines in the Jura mountains.

The

difficulty for a postal historian who wants to figure out the route a

letter took is that letters transiting France to Switzerland from

the United States were not provided some of the same markings seen on

Swiss/French mail. As a result, we get fewer clues from the

piece of mail to isolate the route once it was in Europe. Instead, we

are left to speculate by looking at train schedules and, perhaps,

looking in a crystal ball or some tea leaves.

This cover appears to have been sent from New York City to

La Chatelaine near Geneva, Switzerland. The portion of the address

panel that reads "pres de Geneve" simply indicates that this is

La Chatelaine "near" or "next to" Geneva. The larger, red circular

marking was applied in New York, dated March 9 and indicates that 36

cents of the 42 cents collected in postage is to be passed to France to

cover postal expenses not rendered by the United States postal system.

The French then passed money to the British and Swiss postal systems to cover their parts in carrying this letter.

The breakdown of the postage rate is often not as simple as saying 6 US

cents go here and 12 US cents go there. What can be said entirely

accurately is that 42 US cents were collected via US postage.

Thirty-six of those US cents were passed to the French postal system.

An amount roughly equivalent to 16 US cents was sent in French centimes

(probably 80 centimes) to the English to cover the sea passage and the

transit on British rail from Liverpool and the English Channel

crossing. This left 20 US cents, which is in the neighborhood of 1

franc in French currency, to cover transit through France and the cost

of mail in Switzerland to deliver to the recipient.

For the sake of argument, mail from France to Switzerland cost 40

centimes (French) per 1/4 ounce. So, this double weight letter would

have cost 80 centimes if it originated in France. This rate was split

at 50 centimes for French postage and 30 centimes for Swiss postage.

So, it is not unreasonable to speculate that 30 centimes (about 6 US

cents) was passed on to Switzerland to cover their postage costs.

Did you follow all of that?

No?

Let's try this instead:

- The US retains 6 cents of postage.

- France receives 36 cents from the US.

- Britain receives 80 centimes from France.

- Britain pays 6 pence to the Cunard Line for trans-Atlantic crossing.

- Britain retains 2 pence for internal rail service and the English channel crossing.

- France passes 30 centimes to Switzerland (equal to 30 rappen) for the Swiss mail service.

- France retains 70 centimes for their internal mail.

Now

you're all saying - why didn't just put it this way in the first

place? The answer? I don't know, I think it's because I like to hear

myself write.

All of these amounts are estimations because I am not currently willing

to work out all of the details as to actual exchange numbers between all

of the players. involved. For this excercise, I am operating under a

simple 5 French centime to 1 US cent conversion, though the actual rate

was 5.26 centimes per 1 US cent. In the end, that conversion number

matters less because the actual postage breakdown numbers are filtered

through three sets of postal treaties; the treaty between the US and

France, the treaty between France and Britain and the treaty between

France and Switzerland. In the end, it appears that the French make out

like bandits since their internal rate was 40 centimes for a letter

weighing 10 to 20 grams and they walk away with 70 centimes instead!

There is still plenty that can be explored regarding this cover. If you

look, you will notice several manuscript markings. A pencil "2"

notation certainly was applied to indicate that this is a double weight

letter. I have no idea whether the "53" is a postal marking or a filing

docket placed on the envelope after it was received.

The "12" that is crossed out may well reflect some early confusion by a clerk in New York. They might have expected the item was going to go via Prussian Closed Mail, where that "12" would be an expected credit marking. But, once they realized it was for a double weight letter via France, they crossed it out.

Bremen or Hamburg Mail Treaty to Switzerland

|

| US to Switzerland via Hamburg Mails at double the 19 cent rate. |

Bremen and Hamburg were two Hanseatic cities that negotiated mail treaties with the United States including mail service to Switzerland beginning in July of 1857 at a rate of 27 cents per 1/2 ounce. The rate was reduced to 19 cents in October of 1860 and became obsolete when these mail systems were combined with the North German Union postal system in January of 1868.

Initially, mail packets (steamships) traveled between New York and Hamburg every four weeks , but that increased to every other week (alternating with the ships that traveled to Bremen) as we progress through the 1860s.

Once again, I share an exhibit page for those who might enjoy viewing it.

Mail from Hamburg and Bremen typically traveled through Frankfort

(Hessian territory) and would go through Baden to western Switzerland and Wurttemburg to eastern

Switzerland.

The different numerical markings help us figure out how the postage was shared between mail systems. First, the blue "8" is in the German silbergroschen currency, which would translate to 19 US cents approximately. It appears that the blue "8" was applied in Frankfort A Main, which would imply entry into the Thurn and Taxis posts.

Thurn and Taxis would have

kept 6 silbergroschen for their transit of mail to Switzerland and 2

silbergroschen would have been passed to Switzerland for their surface

mails (about 5 cents). The red marking next to the "8" is "2

fr"* which represented the amount passed to Switzerland.

* this is a weiterfranco marking, weiterfranco is a German postal

term that indicates an amount of postage passed forward to the next

postal service.

British Open Mail to Switzerland

|

| An alert clerk prevented loss of the entire 24 cents postage paid by using British Open Mail |

There was no option to send a letter via the British Mail to Switzerland as a fully paid letter. Instead, the only option was to split payment between the person sending the letter and the person receiving the letter.

In the case of British Open Mail, the US postal patron had to pay the US portion of the postage and the recipient would pay for all postage costs from the point the letter entered the British mail to the point it got to its destination. It is interesting to note that this rate was advertised in rate tables as an option until the middle of 1857. After that, it was not advertised, even though the postal treaty between the US and the UK provided the option for destinations like Switzerland and the Netherlands.

The open mails were especially valuable for mail that was overweight but not paid as such. The sender of this appears to have intended to pay the 21 cent French rate to Switzerland. However, the item must have weighed more than 7.5 grams (1/4 ounce), which would require 42 cents in postage.

The postmaster realized that at least some of the postage applied to the envelope could be useful by paying the US portion of the trip to England. So, the item was sent via the British Open Mail at 21 cents per half ounce, since an American contract ship took this mail across the Atlantic).

- French Mail: 21 cents per 1/4 ounce

- British Open Mail: 5 cents per 1/2 ounce OR 21 cents per 1/2 ounce with remainder to be collected from recipient in Switzerland.

- Prussian Closed Mail: 33 cents per 1/2 ounce (35 cts prior to May 1863)

- Prussian Closed Mail to border: 28 cents per 1/2 ounce with remainder to be collected from recipient.

- Bremen or Hamburg Mail: 19 cents per 1/2 ounce.

-----------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.

Succinct and I finally can see light in the fog of Trans-Atlantic rates. Very well-done Rob.

ReplyDelete