Welcome to the GFF Postal History Blog and Postal History Sunday, which has just celebrated one full year of weekly posts!

Let's start today's offering by taking all of our troubles and worries and tearing them into little strips. Once we've done that, we can mix them with the straw in our poultry bedding. After the birds have had some time to kick it all around and add a little manure, we'll move it all to the compost. Composting is amazing and can turn all kinds of waste into good things. Hey! It works for newspaper and food scraps, so why not all that stuff that weighs on you from day to day?

Now, grab your favorite beverage - but keep it away from the postal history! Put on some fuzzy slippers and sit back. Maybe we'll all learn something new!

-----------------------

There are things in postal history and philately that are popular and desired by nearly all participants in the hobby. It's not unlike popular destinations in the world. If I mention US National Parks, most people will reference Yosemite or the Grand Canyon as two locations that they want to see at least once in their lifetime. If someone travels to Paris, the Eiffel Tower is probably on the "to visit" list.

Popular areas in philately and postal history include zeppelin mail, first stamp issues for a country, and balloon mail (just to name a few).

If

you are a postal historian, it is likely you would love to have an

example of mail carried out of Paris by a manned balloon flight during

the siege by the Prussians in 1870 - 1871. I am no exception - and here

is the lone example that now resides in my collection and is under my

care:

My

primary interests in postal history fall within the 1850 to 1875

period, so balloon mail during the siege clearly qualifies. While there

are many balloon covers from Paris that stayed in France, I am more

attracted to those that left the country. So, I passed on other

opportunities over the years until a recent auction showed up with

numerous items to destinations outside of France.

Happily, I

was able to acquire a letter that ultimately went to the United Kingdom -

and the journey from Paris was an interesting one.

What the Markings Tell Us

Let's start by looking at the cover itself and see what it tells us as we read it.

The letter content is dated January 2, 1871 and this folded letter sheet was mailed in Paris on January 2, 1871. The circular marking in black at the bottom right of the cover is the postal marking that was applied at the Paris post office that received the letter for mailing.

The marking reads: Paris Bt Malesherbes, 6E, Janv 2, 1871. Remember, you can click on each image for a larger version.

If

you look closely at the postage stamps, you will see the number "37" in

the series of dots that cancel the them. This number (37) also appears

in the red circular marking to the left of the stamps. These numbers

are consistent with the district office number assigned by the French

postal system to the branch post office on the Boulevard Malesherbes.

At present, I am not certain why the red marking was struck on this

letter in addition to the black cancellation. (does anyone out there know?)

Yes,

it does seem a little bit much to have three markings to indicated that

this particular Paris post office took this letter in - but that's what

we have here. Maybe there was a clerk that was REALLY concerned that

everyone knew they were still doing their job despite the fact that the

whole city was surrounded by unfriendly troops?

This is a prepaid letter to a destination outside of France, so a marking with PD in a box was applied to show that the 30 centimes required were paid by the stamps (one 20 centime and the other 10 centime).

For

those of you who might be curious, the table shown above lists the

postage rates for letter mail from France to the United Kingdom. The

letter in question would fall under the third rate period shown here, so

the letter could not have weighed more than 10 grams.

The reverse of this letter shows a marking for its reception in Brighton, England on January 11.

It took nine days for this letter to travel from France to England. For context, I have several other examples from this time period where letter mail might take a single day to reach its destination. Because of the long time period between markings, it seems there is an interesting story to tell.

It just so happens that all of the rail

lines and roads leaving Paris were blocked

by German forces starting September 19, 1870 until January 28, 1871.

That would certainly explain delays in the delivery of mail from Paris.

Early attempts to smuggle mail out by land had proved to be

inefficient. So,

if you can't go through the lines, it made sense to go OVER.

That brings us to this:

The words "par Ballon monte" appear on most of the letters carried by manned balloons that left Paris during the siege by German forces. It's at this point that we use the knowledge of balloon flights that have been accumulated by numerous persons over the years who have studied the creative ways mail was carried during the 1870-1 Siege of Paris.

Following the Letter's Path

We know three things from the letter itself.

- It entered the Paris postal service on January 2 at Blvd Malesherbes.

- It was received in England on January 11

- The docket at the top left makes a claim that this was to be carried on a manned balloon flight (ballon monte)

Other things we know from history to help us figure things out:

- The only reliable method of getting mail out of Paris during the siege was via Ballon Monte.

- Not every flight went as it might have been hoped.

- Successfully

flown Ballon Monte mail was typically taken to a French post office in

unoccupied territory so the French postal service could continue the

delivery process.

There are significant

resources from which we can pull out dates and other facts that can

confirm (or deny) whether our letter really did take a trip on a balloon

as part of the process of getting to its destination. If the facts of a

particular flight fit with our postal markings, we can be fairly

certain how this cover got from here to there.

The first balloon launch carrying mail was on September 23, 1870 and a total of 66 balloon flights are recorded as having carried mail from Paris during the siege. A photo taken of the first balloon flight (the Neptune) is shown at the left and was taken from the Wikimedia Commons.

The closest balloon departure to our January 2 and January 11 postmarks would be the balloon called the Newton that departed the Gare d'Orleans on January 4 at 1 A.M. It doesn't hurt to get a picture of where our letter started and where it went next in Paris, so I offer up this amended 1864 map of the city.

We

need to remember that these balloons, filled with coal gas, could do

very little to steer. They were left to rely on the winds to take them

where they will. In the case of the Newton, the light winds were

out of the East and the balloon took a WSW flight in fog, traveling 110

km and landing in German occupied territory at 10:30 AM that morning

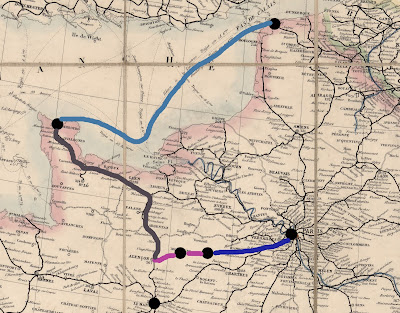

near Digny. The balloon flight is in dark blue/purple on the map below.

Because the balloon had landed in German occupied territory, the pilot and his passenger hid the mail and it was not until January 6 that the regular mail's progress continued. The pilot, Aimé Ours, was able to place the mail bags containing the regular mail at the post office in Mortagne on January 9.

From Mortagne, the mail was taken by coach to Alencon and then by train via the LeMans-Cherbourg line to the English Channel. A coastal ship carried the mail to Calais where it boarded a Channel steamer to Dover in England.

And thus an arrival nine days later on January 11 is justified by a very interesting, and complex, journey.

Who and What Was On That Balloon?

This

balloon was piloted by Aimé Ours, quartermaster of the French Navy,

detached from Fort de Rosny. He was accompanied by an officer charged

with a mission for Léon Gambetta, Amable Brousseau. The balloon was

loaded with six bags of letters weighing a total of 310 kg and a basket

containing four pigeons to be used for return messages to Paris.

The

flight took place in a thick fog and the pilot and passenger had little

idea where they were until they landed. The two men dressed and acted

as agricultural workers to avoid detection. The balloon was folded,

rolled up with ropes and buried while the basket was set on fire to

avoid discovery by the Germans who were patrolling the area.

Brousseau was able to take the "confided" and "privileged" mail, getting it to Alencon by January 5th. Aimé Ours was eventually able to get the regular mail, including this letter, to Mortagne-s-Huisne on January 9, where it continued its voyage to England.

This site (in French) includes more details about the flight and the pilot for those who might like to read more. The image shown above is purported by the referenced site (philatelistes.net) to be Aimé Ours.

Gare d'Orleans

The Gare d'Orleans was the terminal railway station for the line that left Paris to the South towards, of course, Orleans. Since the Paris railway stations were not in use due to the siege, the large buildings provided an opportunity for the construction and housing of balloons for the purposes of sending mail and messages from Paris to the rest of the world.

Gare d'Orleans housed the work directed by the company created by balloonist Eugene Pierre Godard. An assembly line included seamstresses to sew the balloon itself and sailors braiding ropes and halliards. The image shown above is from a wood carving created by Charles Pichot and published in the book, Histoire de la Révolution de 1870 71 by Jules Claretie. The image can be found on page 389.

Soon

after the departure of the Newton, the Germans began a bombardment of

Paris that damaged the Gare d'Orleans and operations were removed to

Gare du Nord and Gare de l'Est. I believe the last flight from the Gare

d'Orleans railway station was the Kepler on January 11th, but I have not had the time to confirm that fact.

What Was In That Letter?

There are numerous reasons why I can only give little snippets as to the contents of this letter. The most obvious, of course, is that the content was in French, which I can read with aid when the text is typed or very well-written. But, what happens when you add inconsistent hand-writing and references to events, sayings, and people you do not know? Well, it gets pretty difficult to decipher it all.

The opening probably should not surprise us since it is written by people who have been under the stress of siege for over three months.

"As we thought of you, my dear ones, at the start of this year there will be so many worries and sorrows for the future!"

At this point in time, the people of

Paris were having to be innovative in their acquisition and preparation

of food. There are numerous stories regarding innovative ways to serve

rat, cat, dog and other animals that could be found for meat. Even the

unfortunate animals in the zoo were offered up for public consumption

(giraffe anyone?).

The letter mentions the fact that the colder weather in January was tough on everyone and trees were being cut down to keep people warm.

Perhaps one of these days I will manage a full translation, but in the interests of actually producing a Postal History Sunday on time, we'll just have to consider doing more on that front for an update post!

Do You Want to Learn More?

There are numerous studies and publications that can provide you with a start if you want to learn more about Ballon Monte mail and how communications were maintained during the Siege of Paris.

New Studies of the Transport of Mails In Wartime France 1870-1 by Brown, Cohn & Walske. Published in 1986, this work has been scanned in and made available to the public. This work shows exactly the level of detail that has been uncovered for these interesting stories in history.

A 2016 Robert A Siegel auction included a large lot of covers that were covered by balloon mail. This just provides us with an example of what a specialist in this area might accomplish as they study the postal artifacts.

The recent 2021 sale by Schuyler Rumsey provided a summary of each balloon flight represented by an item in that auction. This provides interested persons with an opportunity to view actual pieces of mail carried on those flights and get a start on the background for each.

Other items are linked in the text of this Postal History Sunday, but I include them here as well:

Horne, Alistair, The Fall of Paris: Siege and the Commune 1870-71, Penguin Books, 2007 (1st published in 1965).

The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, lithograph and biography for Eugene Godard, aeronaut.

Claretie, Jules, Histoire de la Révolution de 1870 71 for the journal L'Eclipse, Paris, 1872.

There

are many, MANY other references that a person could find and peruse. I

will be the first to admit that my expertise on this topic is limited

and I bow to the work of so many others. Nonetheless, it sure has been

fun to learn something new!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.