Cold days make good days for postal history at the Genuine Faux Farm. This is good news for everyone who might like to read a new Postal History Sunday! Sure enough, here is the latest installment - posted on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog for all who might have interest.

Before

we get started, let's all go dunk our troubles into a tub of water.

Swish them around - get them really wet. Now, let's go hang them on the

clothes line. It's been cold enough it shouldn't take too long for

them to freeze. Once you get done reading Postal History Sunday, go out

and hit them a few times with a shovel or a baseball bat. By the time

you're done with them, they won't look all that formidable anymore.

---------------------------

This week we are going to take a look at mail that was sent from Switzerland to various German and Austrian destinations during the 1850s and 60s. To set the stage, you need to know that Germany was not a single entity during this period. However, most of the German States and Austria operated their postal services under the auspices of the German-Austrian Postal Union (GAPU).

With that in mind, let's take a look at how

postage rates were determined based on the postal convention Switzerland

had with the GAPU.

A simple arrangement

Ok.

I admit it. I am probably misleading you a bit here. Postal relations

between nations is typically anything but simple. My intent is to

actually give you a simple explanation to get us all started and on the

same page - so to speak. Then, we can move forward until we've decided

we have had enough of the complexity. At that point, we can go have

lunch - sounds like a plan to me!

This postal treaty was in effect from October 1, 1852 until August 31, 1868, a fairly significant chunk of time during an era with numerous advances in transportation and strong movements to make postage less expensive for letter mail. The basic idea was that Switzerland would be split into two areas, or rayons, with the first rayon being areas closer to a border with any members of the GAPU. Similarly, the GAPU, covering more territory, was split into three rayons, with the closest being the first rayon and furthest being the third rayon.

Essentially, the Swiss determined

postage at 10 centimes per rayon for a simple letter (a letter that

weighed no more than 15 grams).

Here we are, a folded letter mailed from Basel, Switzlerand on Jun 12, 1866 to Augsburg in the Kingdom of Bavaria, which was a member of the German-Austrian Postal Union. Basel was right on the border with Baden, another member of the GAPU, so it was considered to be in the first rayon of Switzerland. Augsburg falls into the second rayon of the GAPU.

- 1st rayon in Switzerland = 10 centimes in postage

- 2nd rayon in GAPU = 20 centimes in postage

- total postage = 30 centimes.

And

sure enough, there is a 30 centime stamp on this folded letter AND

there are two markings that indicate postage was paid. At bottom left

is a pen marking that is a form of the word "franco," the term favored

by the Germans to indicate that postage was paid. At the center top is

the P.D. marking that was favored by the French.

|  |

Well, that worked out pretty well, didn't it?

The postage is paid and everyone should be happy. So, that leaves us with the question - what is that big red "6" doing on this cover? Didn't we just say the postage was fully paid?

Indeed it is, but we need to remember that postal services during this time were concerned that each of them got their fair share of the postage. The six represents the money the German postal services expected to receive in their currency (kreuzer) to pay for the two rayons worth of ground they had to cover. Six kreuzer was equivalent to 20 centimes of Swiss currency.

Who got the 6 kreuzer?

Just because the German states were part of a postal union, it certainly did not follow that they wouldn't bicker a bit over who actually GOT that six kreuzer.

The simple answer was usually this - whoever handled the letter first got the money.

It just happens that this letter traveled through Wurttemberg first, according this railroad marking that is found on the back of the folded letter. It reads "K. Wurtt. Fahrend Postamt" or "Kingdom of Wurttemberg mobile post office"

Perhaps it would help a little to have a look at a map of the area and we might all have an easier time with what follows.

Switzerland is bordered on the north by Baden and the east by Austria. Wurttemberg shares the border with Switzerland on Lake Constanz (Constance) and Bavaria also gets a tiny little slice of that border on the lake as well.

Basel is located on the western corner of the border with Baden.

Ok - got all of that? No? Well, here's the good news, you can come back to this map as often as you like! What a relief!

Let's give it another go.

Let's send something to Wurttemberg!

Let's

look at an envelope that was sent from Basel, Switzerland in October of

1861 to Fellbach, a small town near Kannstadt in Wurttemberg.

The postage is figured in exactly the same manner as the last item. One rayon for Switzerland and two for the GAPU. Total postage due was 30 rappen (or centimes) - 10 for Switzerland and 20 for the GAPU.

I

suppose it might seem a little concerning that there is no "franco" and

no "P.D." to be found. There isn't even a "6" here to show the 6

kreuzers due to the GAPU. But, the postage stamps have been struck with

the Basel markings so they can't be reused.

Despite all of the differences, there is one similarity. There are one of those Wurttemberg "Fahrend Postamt" markings at the bottom left. Apparently, this letter traveled on Swiss railways until it got to Lake Constanz, where it crossed the lake to Wurttemberg.

Wurttemberg gets the six kreuzer yet again!

Can we make it three for three?

Here's

an envelope that was mailed from Neunkirch, Switzerland in November of

1865 to Stuttgart, Wurttemberg. Neunkirch, like most of Switzerland,

was in the first rayon. And, Stuttgart is just to the west of Kannstadt

and Fellbach - so it is also the 2nd rayon of the GAPU. Once again,

the postage was 30 centimes.

There is a "franco" in black ink shown above. But, the red "6" takes the form of "wf 6," which stands for "weiterfranco 6." You could translate that loosely as "forward payment," which is as good as any description for this process. Switzerland collects 30 centimes of postage and is required to pass forward payment of six kreuzers to the first member of the GAPU that handles this letter.

And, since the weiterfranco

marking is different, that is a clue that maybe - just maybe - some

OTHER German State got to this letter first!

Without

forcing us all to look at each of the postal markings on the back of

the envelope, let me just tell you that one of these reads: "Schweiz

uber Baden." A second marking in blue ink reads "Bahnpost Basel -

Constanz." Both of these confirm that the letter was carried on the

Baden railways and the mailbag had been opened for processing on one of

their mailcars.

So, Baden is the winner of the prize this time around. Which begs the question - how did this happen?

Game of trains

On

the map below are the possible routes letters could have taken from

Basel on their way to Wurttemberg or Bavaria. The blue route uses the

Baden railway lines and the red would be entirely Swiss railways. If

you look closely, you will see that the Baden line actually runs through

a bit of Switzerland up by Schaffhausen.

The numbers on the map correspond to the following cities:

- Basel, Switzerland (our first two letters started here)

- Schaffhausen, Switzerland (our third letter started here)

- Constanz, Baden

- Romanshorn, Switzerland

- Friedrichshaufen, Wurttemberg

Prior to 1863, the Baden line that ran from Basel to Constanz stopped at Waldshut, which means any letter from Basel would continue on its journey via Swiss railways by turning south at that point (note the blue line that goes south and joins with the route in red). But, even then, it is likely Baden opened the mailbags to put their mark on letters and collect their 6 kreuzer just by virtue of handling that mail first!

Once

the letter got to Lake Constanz (also known as the Bodensee), mail

would be carried across the lake to Friedrichshaufen and, at that point,

it would be placed on a mail train controlled by Wurttemberg.

Making the Swiss work hard for one rayon

The

basic idea of rayons was to charge more postage for letters that had to

travel longer distances. The idea of splitting the postage between the

Swiss and the GAPU was similar - to try to compensate each postal

system for the extent of services rendered. If you had to travel more

distance with the letter, you should get more of the compensation.

But,

there was a sneaky thing about the rayons in Switzerland. It turns out

that MOST of the country was close enough to some member of the GAPU

that it was in the first rayon. It did not matter if Basel was next to

Baden and a good distance from Austria - it was still in the first

rayon!

Here is a letter from Basel to Fulpmes (or Vulpmes) near Innsbruck in Austria. Fulpmes was in the third GAPU rayon, but Basel was in the first rayon for Switzerland. The total postage due was 40 centimes, but the sender actually overpaid this item by 10 centimes.

Maybe they

felt bad about the extra work Switzerland had to do for this one? Or

maybe the Swiss postal clerk decided Basel should be in the second rayon

just this once. It doesn't matter, because the official line on this

was 3 rayons for the GAPU and one for Switzerland. With either

interpretation, 9 kreuzer (equivalent to 30 centimes) had to be passed

on to Austria (hence the big red "9" on the front).

The

route of this letter is shown above and there are corresponding

postmarks on the back of the folded letter that match up with these

locations. It's good when the markings confirm the route so clearly!

Thurn and Taxis sneaks in an exception

Just

when we all thought we were getting the hang of this, we learn that

those crazy folks with the Thurn and Taxis postal services had a special

agreement with Switzerland to throw a wrench into the works.

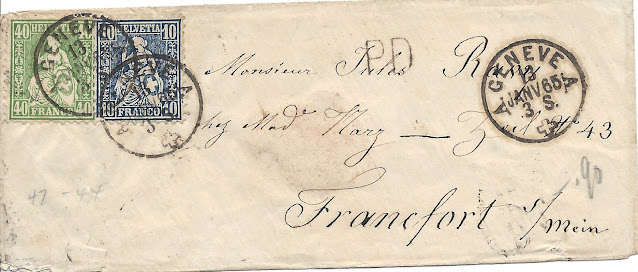

Here is an envelope that was mailed in 1865 from Geneve, Switzerland to Frankfort, in Hessian territory. Frankfort's mail was handled by Thurn & Taxis - but to get there the letter would have to travel through either Baden or Wurttemberg. So, you might expect one of them to get some credit for the postage collected.

Unfortunately for Baden and Wurttemberg, Thurn and Taxis' agreement with Switzerland allowed them to have their mail sent in a closed mail bag* through the other German States. That meant the mail to Frankfort was NOT processed by any other German State and THEY (Thurn & Taxis) would receive the share of the postage due to the GAPU this time around (9 kreuzer = 30 centimes).

Well, I suppose if you had been providing mail services in Europe for centuries, you might know a few tricks to make sure you got paid for your efforts.

The other

interesting feature of this piece of letter mail is that it actually

shows an item that originated in the second rayon of Switzerland.

Geneve was about as far as you could get in Switzerland from any of the

GAPU's borders. And Frankfort was in the third rayon for the GAPU. As a

result, this letter cost 50 centimes to send, the most a single weight

letter (known as a simple letter) could cost.

Bonus Material

At one point in this blog, I might have mentioned that the postage in Switzerland was 30 rappen, instead of 30 centimes (see the 2nd cover in this post). Switzerland actually has four official languages: French, German, Italian and Romansh. The German speaking members of the population would refer to rappen, the Romansh to rap, the Italian speaking to centesimo and the French speakers to centimes. As we move through the 1860s, the official use of centime for the international description becomes widely accepted.

Switzerland first had a unified currency based on the franc in 1798, which was then split into 100 centimes/rappen/rap/centesimo. It was at this time that the French, under Napoleon, created the Helvetic Republic - which lasted only five years. Even after the various cantons resumed control, most continued using forms of the franc and its decimal currency structure. This made it easier for them to adopt this currency when the Swiss Confederation was formed in the late 1840s.

*Bonus Material Part II

Today is a two for the price of one day at the Genuine Faux Farm!

With our last cover, we mentioned the idea of a "closed mail bag" and I thought it might be useful to tell you a little more about that.

Some postal services negotiated the right to send mailbags through an area controlled by a different postal service so that the mail in transit would not be processed by this intermediary country or postal agent. This is often referred to as "closed mail." Letters carried with a closed mail agreement will not have markings from any of the intermediaries for that reason.

Typically, the intermediary service would receive some compensation based on bulk weight or some other consideration.

And now you know at least a little bit about that particular topic!

Have a great remainder of your weekend and a wonderful week to come!