Welcome to Postal History Sunday (issue #77), which is hosted each Sunday on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. For those who are curious, I put the number on here this time because I had someone ask how many entries I have written thus far. It's a good healthy number and I am pleased to have gotten this far with the project.

Now, let's pack all of those troubles into an envelope

and mail it to some unknown address. Make sure you don't put your

return address on the envelope in hopes that they never come back. Put

on the fuzzy slippers and get a favorite beverage - it's time for some

postal history!

----------------------

Last Summer, one of our entries was titled Sneaky Clues, which featured hand-written markings that helped to tell the story of various pieces of postal history. I had so much fun with that one, I thought I'd do it again!

This time, we're going to start with a

letter that was sent from Newport, Rhode Island to Paris, France in

1866. Can you guess what "sneaky clue" I am going to focus on for this

item?

Actually, this time around, I wanted to show how well ALL of the pieces of the story being told by this envelope work together.

The red "45" at the bottom left is equivalent to the amount of postage found on this envelope: one 24-cent stamp, two 10-cent stamps and one 1-cent stamp = 45 cents total.

The postage rate for letter mail

from the United States to France at the time was 15 cents per 1/4 ounce

of weight (effective April 1857-Dec 1869). Forty-five is a multiple of

fifteen, so that's a good sign.

I took a moment to enhance the red pencil mark and remove some of the distracting marks from the address panel so you can better see what it is that I am referring to.

The "3" is in reference to the fact that this letter must have weighed more than 1/2 ounce and no more than 3/4 ounce. In other words, postage needed to be three times the simple letter rate (15 cents). So, this number confirms the amount of postage AND the "45" marking at the lower left. So far so good.

But, what is it with the "36"?

This is where the docket AND the round, red Boston marking come in. The docket reads "per Cunard Steamer of Wed Dec 5th from Boston." The red Boston marking is dated December 5 and states that the postage is paid. It certainly is nice that both of these things agree about when this letter was put on a steamship (the Cunard Line's Africa) - but this is ALSO where the "36" ties in to the whole story.

Of the 45 cents collected in postage by the United States, thirty-six cents were to be passed on to France so they could pay for their expenses AND so they could pass money to the British. After all, the Cunard Line was under contract with the British Postal Service to carry the mail across the Atlantic.

In the end, the postage was broken down as follows:

- 9 cents for the United States

- 36 cents went to the French who used it to pay for

- 18 cents to the British for the trip across the Atlantic

- 6 cents to cover the British surface mail and transit across the English Channel

- 12 cents kept by the French to pay for their own postal expenses.

If

the ship crossing the Atlantic had been for a shipping line that had a

contract with the United States or France, these numbers would be

different, and so would the red pencil markings.

And that's how it all ties together. Why is this interesting or important to a postal historian?

What

would happen if we had a letter that did not have a docket, did not

have the red "45" and the red Boston marking was smeared? If there was

only a "36/3" clearly written in pencil and 45 cents in postage on the

envelope, we could still be able to piece most of the story together

because we've seen items (like this one) where all of the pieces are

completely and clearly spelled out. That's part of the reason why I

have worked to become more conversant in "sneaky clues." Sometimes, not

everything will be as easily read as they are on our first example.

Here is an 1856 folded letter that was sent from Nancy, Franc to Paris. There is a 20 centime stamp at the top right and the red box at the top left reads "affranchissement insuffisant" (insufficient postage).

As a public service, I now give you a table that shows the internal letter rates for France during the second half of the 1800s. I highlighted the text of the row that applies to this letter.

Prepaid Internal Letter Rates for France

| Date | 1st Rate | up to | 2nd Rate | up to | 3rd Rate | up to | Additional | Per |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 1, 1849 | 0,20 | 7.5g | 0,40 | 15g | 1,00 | 100g | 1,00 | 100g |

| Jul 1, 1850 | 0,25 | 7.5g | 0,50 | 15g | 1,00 | 100g | 1,00 | 100g |

| Jul 1, 1854 | 0,20 | 7.5g | 0,40 | 15g | 0,80 | 100g | 0,80 | 100g |

| Jan 1, 1862 | 0,20 | 10g | 0,40 | 20g | 0,80 | 100g | 0,80 | 100g |

| Sep 1, 1871 | 0,25 | 10g | 0,40 | 20g | 0,70 | 50g | 0,50 | 50g |

| Jan 1, 1876 | 0,25 | 15g | 0,50 | 30g | 0,75 | 50g | 0,50 | 50g |

| May 1, 1878 | 0,15 | 15g | - | - | - | - | 0,15 | 15g |

A simple letter would weigh no more than 7.5 grams and would cost 20 centimes. Apparently, the person who mailed this felt the letter was not too heavy and paid the cost for a simple letter. The French postal clerk, on the other hand, did not agree - and they gave us evidence of that fact.

Well, well. It looks the writer exceeded the weight limit by one-half gram (the marking above reads "8 g" or 8 grams).

For reference, 1/2 gram is the weight of half of a typical business card or half of a raisin. It's not much. But, rules IS rules - and this letter simply weighed too much. Which means the amount of postage paid should have been 40 centimes.

At that time, the regulations for short paid mail in France required the recipient to pay the full amount of postage AS IF nothing had been paid at all. In other words, the postage stamp paid for none of the postage required to send this item. Think of it as a donation to the French Post Office if that helps your understanding.It may not seem fair that no credit was given for the postage provided - but at the time post offices around the world were trying to enforce pre-payment of letters. Maybe a few harsh economic lessons would be enough to get the point across?

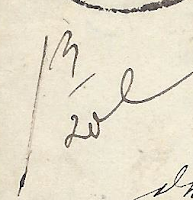

So, the amount due to the recipient was 40 centimes, which is represented by the big squiggle shown in the image at the left. Yes, that is a "4," which stands for 4 decimes (equal to 40 centimes). Remember, the French often used decimes for postal accounting, which is the equivalent to Americans referring to 4 dimes instead of 40 cents.

Now, if you are still staring at the squiggle and STILL don't see a "4," I understand. This just might be one of those times you're just going to have to trust me.

Uh oh! Here's that Thurn and Taxis post again! Take a look at this 1865 folded lettersheet mailed from Sonneberg (Thuringia) to Leipzig (in Saxony). Thuringia was another area, like the Hessian States, that used the house of Thurn and Taxis for their mail services.

The target-like cancellations on the stamps have the number "265" in the center, which was the number assigned to the Sonneberg post office. The pencil number "265" with an arrow pointing to the purplish marking was put on the cover by a previous collector. The intent is probably to indicate that they determined that the purple marking was also applied in Sonneberg.

This marking indicates that the letter was sent as a "registered" letter (Recommandirt). In order to register a letter, an additional 6 kreuzer in postage was required. And, some of the numbers found on this cover - those at the top right - are numbers used to track the progress of this letter as it traveled to its destination. The "293" was likely the number in the Sonneberg ledgers that tracked this letter's departure and "205" may well have been Leipzig's ledger number to record the reception of the letter at their office.

So - we have 6 kreuzer spoken for - that leaves us with 12 kreuzer in postage paid.

The rate between Sonneberg and Leipzig was 6 kreuzer per loth. At the time, mail in the German States included both a distance and a weight variable to determine the postage required. The distance between the two cities was between 10 and 20 meilen (German miles) - if they had been closer it would only cost 3 kreuzer per loth.

And, there it is! Our sneaky clue resided at the left, just under the postage stamps. This scrawl in black pen reads "1 3/20 L," with the "L" standing for loth, the weight unit in use by German postal services at the time. One loth is roughly equivalent to a half ounce.

So, this letter weighed over one loth and no more than 2 loth, which made it a double weight letter and the total postage needed can be calculated in this fashion:

- Registration Fee 6 kreuzer

- Rate per loth for distance between 10 & 20 meilen - 6 kreuzer x 2 = 12 kreuzer

- Total = 18 kreuzer

Here is another piece of French postal history to consider from 1864. This item was also sent as a "registered" item (Chargé). But, that's not what I want to focus on this time around.

This item was returned to the sender, which would have been the Tribunal Court in Chambery. The contents are a court summons that apparently did not find the person they were "summoning!"

But, how did I know this was returned to the sender?

The sneaky clue is at the bottom right, just under the Chambery postmark. The words "au dos," when placed on a piece of letter mail explains that the carrier or clerk should "look on the back" for more explanation. So, I looked on the back - and this is what I found:

The word "Inconnu," which would translate to "unknown." The post office in Chambery was unable to locate the recipient of this court summons and they simply returned it to the Tribunal.

Well, if the postal service can't find you, I guess you don't need to go to court.

Let's close with this 1867 envelope that was sent from New Orleans, Louisiana to Kurnik, Prussia (now in Poland). The postage applied is 28 cents, which is the correct postage for a simple letter sent to Prussia (not weighing more than 1/2 ounce). The New Orleans, New York and Aachen markings clearly show the travels this letter took and the dates it visited each location. A single marking on the back tells us it arrived at the destination post office on April 15.

But, what is all of this? The use of blue and red pencil might be an indication that there might be some postal significance - but what?

I

have to admit that I have been puzzled by these markings for some

time. The numbers "15" and "4" really don't connect to any postal rate

calculations that I could determine. And, there was no reason (and no

way) for this item to have traveled through Orleans, France.... unless

that is not the word "Orleans" written in blue.

So, this particular set of markings sat in my "to be solved" list for a long time. Until, one day, I asked the right people and got an answer that makes perfect sense.

This is a docket written by the recipient, simply recording that the letter was received on the 15th of April (4th month) from Orleans (New Orleans). The little red squiggle before the numbers was simply an abbreviation to indicate a received date, which matches the date of the postal arrival date on the back.

Sometimes

the answer is so simple that it is almost embarrassing to admit it to

others. In this case, I think I can hide behind the fact that most

Americans list dates in month/day order rather than day/month order.

That's about the only defense I have right now - but I do feel much

better now that the mystery is not so much of a mystery any more.

-------------------------------------

An Answer to a Question

I received the following question from an individual who has read a few Postal History Sunday entries and I thought it was worth repeating it and my answer here as a bonus for today.

Q: What is it that attracts you to the postal history you share on Postal History Sunday? How do you pick the items you feature?

A: The answer can actually get very long and I probably cover it on and off in various Postal History Sunday offerings. But, this one, titled Favorites, probably sums it up pretty well if you are willing to go read it.

If you aren't willing I can sum it up this way. I like learning new things. I like puzzles. I like history. I like the artistry found in the stamps, the handwriting and the papers of the time. And... I like to try to figure out complicated things in history and then try to find the right words to make it easier for someone else to understand the same things I do.

As far as how I pick the items I feature -

every item I show is in (or was once in) my own collection unless I

clearly state otherwise under the image. I like to focus the most on

the mid-1800s and I tend to have more connections to the US and European

mails. This might be enough to explain why you see so much of some

things and less of others. We all have our limits, and I have a long,

long way to go to conquer every area covered by postal history.

This s a great service to philately, and will probably draw more collectors into studying and buying postally historic items.

ReplyDeleteThank you for the kind words. It is appreciated.

Delete