Welcome to Sunday everyone! It's time for Postal History Sunday, hosted on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog.

As

is sometimes the case, I got so absorbed in writing that I forgot to

write a good introduction. So, rather than even try - let's just get

right to all of the fun and excitement!

---------------------

As is true in any area of life, there is knowing something and then there is knowing something.

Today's entry is one such example in my own journey of learning in the

realm of postal history. And it all centers around one simple postal

marking that I show below:

|

What you see is a cleaned up scan of what looks like an ornamental ring, something a person might wear, with an "R" in the center. My personal discovery of this marking came many years ago, as I was seeking out examples of the mail between the United States and the United Kingdom that bore the 24-cent value from the 1861 series of postage stamps.

At that time, I was keen to find variations on the mail that was most commonly going to bear that stamp. This was my focus for economic reasons - it was the most common use of my selected stamp, which means they typically cost less. This was also my focus for educational reasons, because it encouraged me to dig around and see what I could learn beyond the basics.

|

| 1867 cover to London from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas |

And here it is, the cover that introduced me to

the postal marking in question. Let's start with the basics and go from

there - just like I did back when I first acquired this cover. The

initial attraction, at the time, was the 24-cent stamp (shown below).

While the stamp isn't the prettiest copy I've ever seen, that wasn't the

goal here. The goal was to learn how this stamp was actually pressed

into service to carry mail.

The postage rate

The

active postal convention at the time had been agreed upon in 1848.

This postal treaty set the postage rate at 24 cents for the first

one-half ounce of weight for letter mail. The corresponding cost for

mail from the United Kingdom (UK) to the United States (US) was 1

shilling.

The red marking at the top center of the envelope is a bit difficult to read, but I have had some practice and can tell you that it reads "N. York 3 Am Pkt Paid" and is bears the date May 4. This particular marking tells us several things.

- The letter was considered paid by the clerk at the New York City exchange office for foreign mail.

- Three cents were to be passed to the United Kingdom for their share of the postal expense.

- 21 cents were retained by the United States to pay for their expenses, including the cost of sending the letter across the Atlantic.

- The steamship would leave New York on May 4, and it held a contract to carry mail for the United States.

Even

today, as I write Postal History Sunday blog posts, I am amazed by how

much we can learn from a simple marking on an envelope. At the time,

these were the basics that I was becoming increasingly comfortable

reading as a viewed more of this kind of cover.

How it got to London

This

letter was mailed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas on April 29 of 1867.

From there, the letter likely rode on various trains to get to New York

City. I would suppose, if someone wanted to do some digging, a likely

railway route could be determined. But, that's not my focus this time

around.

Upon arrival at New York City, the letter was processed by the exchange office and placed into a mailbag that was sealed and taken to the HAPAG line's Cimbria for carriage across the ocean. This mailbag was dropped off at Southampton on May 14 and arrived at London the next day where their exchange office took it out of the mailbag and placed their own red circular marking on the envelope at the bottom.

Where it got a bit more interesting

The first address on the envelope reads "Nr 4 Upper Seymour St. Portman Square London W." But, that address has been crossed out and a new address is written at the top right that reads "22 Princes St. Cavendish Square W." And then, there is that ring with an "R" in the middle.

So, clearly, this letter had been redirected to a new address. Miss Mary Rush was no longer at the Portman Square address in London and the Rushes had relocated to Cavendish Square. After a few questions and a little bit of looking, I learned that the "R" essentially indicated that the letter was "redirected" to the new address.

Portman Square is located at the far left center and Cavendish Square is

to its East. This is segment of an 1817 map of London by William

Darton. Remember - you can click on images to see a larger version of the image if you wish!

Well, ok then. That makes sense, so I wrote my descriptions up with that information and went about my merry way - happy to have learned something new.

Another piece of redirected mail in the UK

As

I continued exploring mail between the US and the UK, it was logical

that I would see other items that were redirected to a new address.

And, as I explored each one, I began to see a fundamental difference

that required an explanation. For example, here is another letter that

was mailed in 1865 from Washington, D.C. to Birkenhead in the UK.

|

This letter weighed more than a half ounce, but no more than one ounce - so it required 48 cents in postage. If you'll notice, there is a red "38" that tells us the British post was to receive 38 of those cents for their share of the expenses. This time around the ship had a contract with the British so THEY paid for the crossing of the Atlantic.

Once again, we will notice that the original address in Birkenhead has been crossed out. And, if we look closely at the bottom left, it looks like the sender of this letter was aware that the addressee might have moved on. The docket requests that the letter be forwarded by Isaac Cooke, who likely knew where Mrs. W.H. Channing might be.

Mrs. W.H. Channing? Why does that sound familiar? Oh, yes. Our first Postal History Sunday of the year focused on ANOTHER letter to Mrs. Channing!

But, there is a problem! Where is the new address?

Ah ha! It's on the back! And, not only is the new address in Hastings, Sussex found there, so are two one penny stamps to pay for a domestic letter that weighed over a half ounce (and no more than one ounce) in the UK.

Wait a minute! They had to PAY to have this letter forwarded or sent to the new address? I don't remember that with the first item.

It's all about WHERE it was redirected TO

For a longer time than I am willing to admit, I did not explore the fine distinction between these two letters. I called the first item a "redirected" piece of mail and the second item was "remailed" or "forwarded." And all of that is technically correct. But, that did not mean I was completely aware of how the British post distinguished between the two.

|

So, back to the original item. There is NO evidence

of additional postage paid and there are no additional postal markings

other than the ring with an "R" in it. So, why would this letter have

this special marking and the other one does not? So, I went digging

into the regulations for the forwarding of mail in the UK.

The Post Office Act of 1840 (link is to the Great Britain Philatelic Society site) set the rule that a new rate would be required for an item requiring redirection. In other words, the item had to pay the postage AGAIN in order for it to travel through the mail to the new location. This seems to match up with the 2nd item I shared - the one that shows additional postage stamps on the back.

The text from the postal act is below and was effective on Sep 1, 1840:

Article XIV. And whereas Letters and Packets sent by the Post are chargeable by Law on being re-directed and again forwarded by the Post with a new and distinct Rate of Postage: be it enacted, That on every Post Letter re-directed (whether posted with any Stamp thereon or not) there shall be charged for the Postage of such Letter, from the Place at which the same shall be re-directed to the Place of ultimate Delivery (in addition to all other Rates of Postage payable thereon), such a Rate of Postage only as the same would be liable to if prepaid.

It is not until we look at the British Postal Guide of 1856 that we find an explanation for our first cover (the one shown above). Apparently, if the new location is WITHIN the same local delivery area, no additional postage is needed and the letter can simply be redirected to the new address. AHA!

The text from that resource is shown below for those who might like to read it.

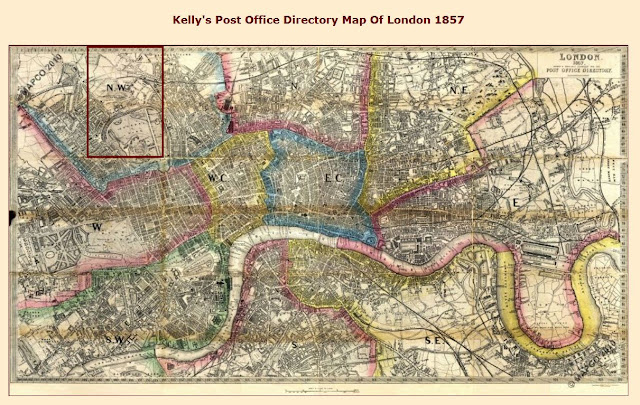

The above makes the process fairly clear that an item redirected within the jurisdiction of any "Head-Office" or one of its "Sub-Offices" would be redirected without additional charge. Below is a London Post Office Directory map from 1857 that may be accessed and viewed in more detail at the Mapco site. It is my assumption at this time that each "Head Office" referenced in the Postal Guide translates to each of the sections shown here designated by directional markers (NW, N, EC, WC, etc).

Portman

Square and Cavendish Square are both within the Western postal district

and not far from each other. Additional postage was NOT required for

our first item. Since there isn't additional postage on the cover,

that's a good thing to learn. The second cover goes to a different

postal district, so it had to have extra postage. Everything seems to

add up. So, let me throw another wrench in the works!

|

| Redirection Fee waived, but no marking |

Here is another letter that was sent from the US to the UK. The initial address has been crossed off and a new one has been written at the top left. There is NO additional postage. Both address are in Holloway, a district of London currently part of the borough of Islington (about 3 miles North of Charing Cross). This would be in the North postal district according the Kelly's map above - and the initial address does read "Holloway (N)."

But there is no "R" in ring marking - what's with that?

The R in Ring Marking

|

| from Mackay's "Postmarks of England and Wales" (1988) |

Julian Jones was kind enough to provide help, giving

me a reasonable summary and this quote from a book by James Mackay

(pages 281-282).

"Letters from the 1840s onwards, redirected in the same delivery area as the original address and therefore not subject to any further charge, were marked with small circular stamps surmounted by a crown and having the letter 'R' in the centre. These stamps varied considerably in diameter, the style of the letter and the shape of the crown. Ten identical stamps (5290 shown above) were issued to the London district offices on 5th April 1859."

First, you might notice that my example of the marking does not clearly show the "crown" at the top of the circle, so it makes sense that I would initially think of it as a ring. It's a first impressions thing - I have a hard time now thinking of it as anything else.

These were an inspector/examiner marking used for redirecting post within a local area of London. The application of this marking indicated that the item was NOT subject to additional postage for the redirection to a new address. These R in Ring markings are known in both red and black inks.

This, of course, now begs the question as to why the second cover does not exhibit such a marking. I suppose, it is possible that the carrier learned of the new address while on the route and simply took it there without coming back to the post office. That might explain the absence of an additional marking. Or, perhaps the Holloway post office in London wasn't given a marking device. We'll just call these "things to contemplate for the future" should the opportunity to learn more present itself!

Bonus Material!

There are a few additional points of interest that come along for the ride with this Postal History Sunday!

1. The Cimbria was a new ship

The sailing from New York to Southampton on May 4th, 1867 was the return leg of the Cimbria's maiden voyage. This steamship had left Hamburg for the Hamburg-American Line (HAPAG) on April 13 and successfully delivered passengers and mail.

This was also a point of interest to me early on because this was also one of the "little differences" in a postal history item that provided me with more interest - even if it was "only a common use" from the US to the UK.

The Cimbria would serve well until 1883, when tragedy struck. The steamship collided with a British vessel by the name of the Sultan (Hull & Hamburg Line) not far from Borkum Island, after which the damaged Sultan "drifted off into the fog" despite screams and calls for help from the Cimbria. The current HAPAG-Lloyd site includes a summary of the event.

The Cimbria sank rapidly, taking 389 lives with her and only 133 were saved on seven lifeboats that were successfully launched. More information can be found at the Wreck Site, which includes the following unattributed newspaper clipping.

And, if you want even more information about the ship itself, one of the best resources is North Atlantic Seaway by N.R.P.Bonsor, for specific information on Cimbria go to vol.1,p.389

2. Not THAT Benjamin Rush, but related

If you are familiar with Revolutionary War period history, you might perk up at the name Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. Well, this is his grandson, who was a writer and a lawyer.

Of particular interest is this item, that is titled "William B. Reed, of Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia. Expert in the art of exhumation of the dead." Yes - that is quite the title - is it not?

Of particular interest is that this publication was being sent to the United States on a steamship DEPARTING the UK on May 4th, 1867.... the same date the Cimbria set off from New York, carrying our featured letter to Mary Rush. These two things must have passed each other on the Atlantic Ocean.

In about fifteen pages of text, Rush

takes on William B Reed, who apparently had taken it upon himself to

sully the name of Rush's grandfather and namesake. A small segment of Rush's writing is below, from the

site listed above.

3. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

You might recognize the name of Leavenworth for the federal prison that was built in the 20th century. but, in the 1860s, Fort Leavenworth was actually a key training point for Union soldiers in an effort to hold an area that actually had strong feelings for the Confederacy.

This 1867 photo by Alexander Gardner can be found at this location and one brief history can be found at the site that hosts the photo found above. A contemporary event at Leavenworth would be the court martial of General Custer in August of 1867.

For good measure, here is another contemporary photo from the Library of Congress. Why not? Let's do this thing right.

------------------------

Thank you again for your interest in Postal History Sunday. I hope you enjoyed today's entry and that you learned something new. I know I did!

Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come!

Your "unattributed newspaper clipping" of the loss of the Cimbria is probably from one of the many newspapers that reported the judgement, that had been given on 17 December 1883, on 18 December and subsequently in British newpapers. Their reporting included but was not necessarily limited to that same wording as given in your clipping, which was an extract from a Reuters report.

ReplyDeleteThank you, this is excellent information to have and fills things out very nicely.

Delete