Welcome to this week's entry of Postal History Sunday. PHS is hosted every week on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. Everyone is welcome here, regardless of the level of knowledge and expertise you might have in postal history.

Put on the fuzzy slippers, find a comfy chair, pour some of your favorite beverage and take a moment to put those troubles out of your mind for a few minutes. Personally, I took advantage of the approaching snowstorm and left my troubles in a spot where the snowdrifts are most likely to form. With any luck, it will be a couple months before they are visible again.

Where did you think Guernsey Cattle came from?

If you happen to be a person who has expertise or knowledge of a specific skill or knowledge area, you might be familiar with a question that goes something like this: "It looks/sounds/feels like all of these others, so what makes THIS one so special to you?"

This can hold true for postal history, as it does for many other things. For example, the envelope shown above just looks like another 1860s cover from the United States to the United Kingdom. As a matter of fact, it isn't even a very pretty example if I were to make that judgement. It has a 24 cent stamp paying the proper postage for an item that weighed no more than 1/2 ounce. There is a New York exchange marking, dated September 29 in red, that tells us it was properly paid. End of story. Right?

This is where I encourage you to read the address carefully and I wait with baited breath until you notice that this is sent to Guernsey. Then I get disappointed when you say, "so what?" So, I take the easy way out and send you to a wikipedia page on Guernsey in hopes that you get it. And you still look at me expectantly. I mean, Guernsey is just one of the Channel Islands off of the Normandy coast of France. What's the big deal?

There you have it. When a person dives deeper and deeper into the details of some subject that they love, they begin to see bigger differences in the details that seem minuscule to others. But to those of us who do dive into these depths, we see it as rewarding. It's a chance to uncover a story that is different from so many other covers to the United Kingdom at this time.

For the time being, I will simply say that one does not find letters from the US to the Channel Islands very often from this time period. I will also point out to you that Guernsey is NOT part of the United Kingdom - at least not in the same way Scotland or Wales might be. Guernsey is a sovereign state, though it is a Crown Dependency. They enjoyed the same postage rate from the United States as England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland despite a slightly different status. The island of Guernsey even has a traditional local language (Guernesiais).

This particular item is an introduction to this week's theme, "Splitting Hairs," where I thought I'd share a few items and point to the thing (or things) that make them stand out (at least to me) as different.

Le Havre for the win

So, here is a folded letter from the United States to France in 1866. The postage rate at the time was 15 cents per 1/4 ounce. This item must have weighed between 1/4 and 1/2 ounce, so it required double the base rate. The 24-cent stamp is combined with two 3-cent stamps to properly pay the postage.

As far as examples of the double rate in the 1860s to France go, this one seems pretty normal. It's properly paid. It has all of the normal markings. It was mailed in Ballston, New York and it went through the New York exchange office. There is a "P.D." marking that shows the French also recognized this item as fully paid. The letter took the Cunard Line's steamship Java to Queenstown (Cobh, Ireland) where it was offloaded and took the mail trains to London.

It's all pretty normal until it came to crossing the English Channel to France. Hmm.. it seems the English Channel has a great deal to do with this week's Postal History Sunday.

The hair splitting occurs with this French marking and the indication that it entered France at Havre. The marking reads "Et Unis Serv Br Havre" around the outside edge of the octagonal shape (United States, British Service to Havre). This marking confirms that a British contract ship (Cunard's Java) carried the letter and that the mailbag carrying the letter was handled by the British Post.

Typically mail via England to France would enter France at Calais if it came via the United Kingdom. But, this letter is addressed to Havre and it was likely carried across the English Channel on a private steamer, rather than the normal contract steamer that carried mail to Calais.

Once again, the vast majority of letters during this time period would not have taken this route - but this one did. This makes it interesting to me as it illustrates another option for mail carriage that came about because getting mail from every point A to every point B is bound to have many complexities.

We just don't see some of those complexities unless we really look for them.

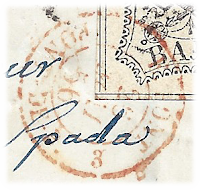

A German state of mind

Our next item of interest was mailed from the United States to Germany in 1865. The postage rate was 28 cents per 1/2 ounce and this letter overpays that rate with thirty cents in postage. This is not terribly surprising because the postage rate had been 30 cents prior to a rate reduction to 28 cents for prepaid mail (the rate for unpaid mail remained at 30 cents). Essentially someone either didn't know the rate had changed or they misread the postage rate tables and saw the amount for unpaid mail and used that.

At the time this item was mailed, Germany was not a unified nation. Instead, it was a number of separate governmental units that are collectively referred to as the German States. At this time, the German States and Austria had a postal agreement that allowed all members to treat mail between the participants as if it was internal (domestic mail). This agreement is often referred to as the German-Austrian Postal Union (GAPU) to English-speaking philatelists or Deutsch-Österreichische Postverein (DÖPV) to those who speak German.. If you would like to learn more about it, I can offer you a look at a similar agreement between Austria and some of the Italian States.

The net result is that the postage rate from the US to members of GAPU was the same (28 cents) with a few exceptions I might write about in the future. Because of this, some postal historians are just as happy to say this is a letter to Germany, just like THIS is also a letter to Germany.

It just so happens that many of the German States that were in GAPU maintained their own postal systems, or they contracted with the house of Thurn and Taxis. So, in a very real way, each German State could be considered a separate destination during this period in history. Most surviving mail from the US in the 1860s to Germany would be to Prussia, Bavaria, Baden, Wurttemberg, Hannover or even Saxony (as shown above).

Brunswick just doesn't show up as often as the others do, which makes it interesting to me. Still, regardless of how common or uncommon a particular German State might have been as a letter destination, it is the fact that these different states had their own postal services that grabs my attention. This is why I split hairs and pay attention to which German State a letter goes to in the 1860s, rather than simply saying, "oh, this went to Germany." The finer distinction reflects a reality of the world during that time period, where Germany was split into many entities - but in the process of uniting into one.

Three hairs to split with one cover

Here is a letter from the US to Italy. Like Germany, Italy was divided into multiple states. But, by the time this letter arrived in 1866, only the area around Rome was separate from the rest of Italy. The postage rate for mail to Rome, sent via France, was 27 cents per 1/4 ounce. This letter bears 27 cents in postage and was marked as having been paid to its destination in Rome.

This particular letter has more than one detail that is a bit different than other, similar, letters.

First, the letter was forwarded to a new location, Genzano, which was located outside of Rome. If you look, you will notice that Rome was crossed out and Genzano is written in different ink just below it. The number "15" written in red ink towards the top of the envelope told the person delivering the letter that they needed to collect an additional 15 centesimi to pay for mail carriage from Rome to Genzano.

Second, if you look at the slip of white paper with the arrow on it, you might recognize that this envelope was cut. This item was likely disinfected at Genzano in response to the cholera epidemic at this time. It was pretty well known that disinfection of the mail was not going to help prevent the spread of cholera. But, some local governments wanted to be seen as doing something (maybe anything) to protect the public.

And finally, this letter was carried by the Havre Line's Fulton. If you'll recall, our second letter was special because it entered France at Havre via a non-contract British Channel steamship. This letter, however, was carried by a steamship company that crossed the Atlantic from New York to Havre in France under contact with the United States. This steamship line only carried 5.1% of the mail from the US to Europe in 1866.

I suspect that's about as much "splitting hairs" as some of you are interested in for one day. So, now that I've made that point, let's provide you with some...

Bonus Material

Let's return to our first item that was sent to Guernsey. Since Guernsey is an island situated off of the Normandy coast (France), mail had to be taken there by a steamship or sailing vessel. A route from Southampton (England) to Guernsey and Jersey (also a Channel Island) was maintained by the New South Western Steam Navigation Company until 1862 when an Act of Parliament allowed the London and South Western Railway Company to own and operate ships. The first ship built for their Channel Islands route was the Normandy.

The Normandy was an iron paddle wheel steamer that made its first voyage to the Channel Islands on September 19, 1863. This letter would likely have been on one of Normandy's earliest trips, arriving in Guernsey on Oct 12, 1863.

|

| Normandy off the coast of Jersey - painting by Philip Ouless |

The Normandy suffered damage in a collision with the liner Bavaria in April of 1864, but is best known for a catastrophic collision on March 17, 1870 with the SS Mary.

According to the account found in the Annual Register for 1870 (starting page 26), both ships were sailing in a dense fog and sighted each other too late to avoid collision. The Normandy, broke into two pieces, with its lifeboat getting separated from the crew and passengers. Two other boats were able to leave the Normandy successfully with thirty-one individuals. The captain of the Mary sent a boat under the command of his first mate to pick up survivors, but this boat turned back before reaching the Normandy, claiming to be unable to find the sinking ship in the fog.

Thirty-four individuals perished as the Normandy sank. Meanwhile, the Mary stood by to render assistance as long as they dared. But their own situation was doubtful because the Mary had a sizable hole in the bow of the ship. The ship was lightened by tossing a significant amount of its cargo (corn) overboard so it could return to Southampton. Observers at Southampton marveled that the ship survived long enough to get to the harbor safely.

The official inquiry that followed found the Normandy to be at fault, but also felt the first-mate of the Mary had "no valid reason" for returning to the Mary when he did without trying harder to find the sinking ship.

As for the mail that was on the Normandy in 1870, it was lost - mostly. The lone exception was a single bag of mail that was discovered floating on the water's surface. Those mails were eventually delivered. And, no, my envelope was not one of those pieces of mail since the one I illustrate is from 1863 and the sinking of the Normandy was six and a half years later. But, finding an item from that floating mailbag would really be something, wouldn't it?

Thank you for joining me for this week's Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.