Welcome to this week's entry of Postal History Sunday. PHS is hosted every week on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. Everyone is welcome here, regardless of the level of knowledge and expertise you might have in postal history.

This week's post builds off of last week's post. Both of these posts are on items that were featured in a virtual presentation I was honored to give to the Collectors Club of New York on February 1. The video of this presentation will be available for the next few days - until the next installment of their Virtual Collectors Club Philatelic Program Series is completed on February 15. After that point in time, the presentation will be available to members only.

This

slightly worn item is the focus of today's exploration. The ink has

eaten into the paper in places and there is a little staining and

fading. But, the story that surrounds this piece of postal history is a

good one. I'm going to focus first on explaining how it got from here

to there. If I still have the energy at the end, we might get into some

of the social history.

But, let's start first with some of the ground work to help us understand what is going on here.

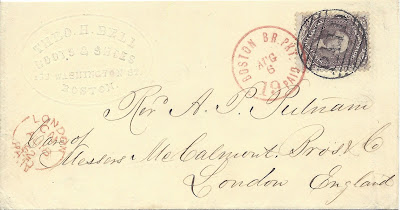

Baseline #1: US to the UK

Last week's Postal History Sunday actually covers this example and I'll refer you to that post for the details. Some basic information we want to take away that will help us understand our focus cover are as follows:

- the postage rate was 24 cents for a simple letter from the US to UK weighing no more than 1/2 ounce.

- a properly paid simple letter typically had a US exchange marking in red.

- these letters usually had an exchange marking, in red, for the United Kingdom.

- the exchange markings usually had the word "paid" somewhere in the design.

Baseline

information becomes valuable for a postal historian because it helps us

to find patterns even when a cover gets more complex. These are

building blocks for mail in the 1860s, and I find it useful to study

these "typical" items so I have the tools to work with "atypical"

covers.

Baseline #2: UK to Italy

Our next example is a letter mailed from Manchester, England to Naples (Napoli), Italy in 1865. This particular folded letter is not quite a perfect baseline item because it is actually an example of a letter that weighed MORE than a simple letter. The postage stamp provided 1 shilling of postage (12 pence), so this letter qualified as a double weight letter, weighing more than 1/4 ounce and no more than 1/2 ounce.

For the duration of this postal agreement (1857 to 1870) mail from the United Kingdom to Italy via France went by closed mail. When we say something went by closed mail we are referring to instances where letters were put into mailbags in one country, but traveled through one or more intermediary countries (or mail services) to get to the destination. In this case, the French agreed to carry mailbags between the UK and the Kingdom of Italy, but the French did not process any of the individual letters. Instead, France received compensation for their services based on bulk amounts (total weight of letters carried).

The take-away here is that we will see markings on this folded letter from the United Kingdom (Manchester and London) and markings for Italy (Napoli). But, we will not see any French markings because this letter was not handled individually by French mail clerks.

So, how do we know this letter even went through France? After all, once it leaves the UK, the next marking is Napoli, which is in southern Italy! The first clue is the docket at the top left that reads "via France and Sardinia." This directional marking gives us a clue that the letter was intended to go overland. But, a good question to ask now is whether these directional dockets were always followed - and the answer to that is "usually, but not always."

In this case, we are supported with the

knowledge of the options for mail from the UK to Italy. The default

route was overland via France and Sardinia in 1865. The other

alternative with the same postage cost was via France and then by

steamship from Marseilles to Naples. A third option, via German mails

was available, but the rate was 11 pence per 1/2 ounce. So, it is safe

for us to conclude that the default route - the same as the one directed

by the docket - was taken through France.

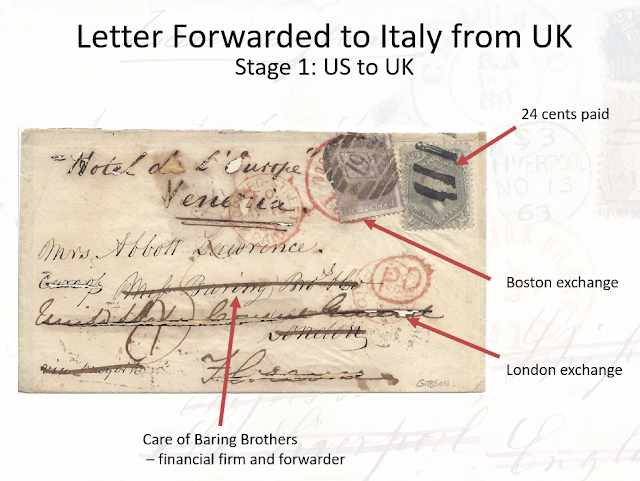

Using the baseline examples

Since I am today's tour guide, let me give you a preview of where we are going. This envelope was mailed in Boston during the year 1865. It was initially sent to London, was then forwarded to Florence (Firenze) in the Kingdom of Italy. After that, it was forwarded again to Venezia (Venice), which was within the borders of the Kingdom of Venetia. Venetia, in turn, was under the control of the Austrian Empire at the time.

Sometimes, and in some places, the description you just got

in the prior paragraph would be enough - maybe more than enough. But,

around here, we like to explore HOW to see these things when we look at a

cover. We also like to be able to explain WHY everything fits

together. If something still seems out of place once the description is

complete, it might be an indicator that there are more opportunities to

learn.

The first step is to recognize the indicators that this letter traveled from the United States to the United Kingdom. There is a 24-cent stamp, which pays the proper postage for a letter that weighed no more than 1/2 ounce. The Boston (US) exchange marking is obscured by a British postage stamp that has been adhered over that mark. Because it is applied with red ink, we know Boston considered the item to be properly paid for. We can also guess the Boston exchange marking looks a lot like the one in our first baseline example.

There

is also a London exchange marking that indicates the letter was

considered to be paid when it was taken out of the mailbag. This letter

was then delivered to the Baring Brothers, a financial firm that

provided services to Americans abroad. These services included holding

mail until the traveler came to pick it up or forwarding mail to the

traveler's next known location.

The red Lombard Street postmark includes the word "paid" and it also includes the letters "F.O." which stood for Foreign Office. Like our second baseline example, you will see the "PD" in an oval and a London exchange marking on the back of the envelope. Also, like our second baseline item, there are no French markings on this envelope, even though it was carried through France.

So, how do we know this one went through France?

This time, we have no directional docket, but we do still know that the default route was overland through France and Sardinia. Also, the first Italian mail marking we see is the Susa-Torino (or this could be Susa - Modane) marking on the back of the envelope. This would be the traveling post office on the first railway in Italy that is just east of the Alps crossing between France and Italy.

The major passes through the Alps where mail to Italy was regularly carried can be seen below. Three passes would have required the letter to travel through Switzerland. The other two were in France and Austria. If you would like to learn a bit more about the Modane Tunnel and the Mount Cenis Railway, this contemporary article from Harper's New Monthly Magazine might be of interest (No. CCLIV.—JULY, 1871.—VOL. XLIII).

That's enough information to be conclusive, this letter went via France.

There is another circular marking that is not a postal marking - it was applied at the U.S. Consulate General's office in Florence. The Consulate General was (and still is) "responsible for the welfare and whereabouts of US citizens traveling and residing abroad." The existence of this marking gives us another clue that the letter was probably to a traveling US citizen who was in Italy in May of 1865.

Unlike the Baring Brothers, the US Consulate General did not have a financial account with the traveler. The Baring Brothers could deduct any costs for forwarding postage from the line of credit established for the traveler. The US Consulate, on the other hand, would forward the mail, but they were not likely to pay the postage - though I admit it could be possible.

There are two more markings on the back of this

envelope that chronicle this last segment of travel. The first reads

Pontelagoscuro, Ferrara. If you will take a quick look at the map shown

below, Ferrara would be located near the border of Romagne and

Venetia. What we need to know about the status of Italy in 1865 was

that Romagne was part of the Kingdom of Italy. Venetia, on the other

hand, was not. Venetia was under the control of Austria and the

Austrian postal system.

Once again, there is a protocol to exchange mail between two different postal services. The Ferrara marking served as Italy's exchange marking, while the Venezia (Venice) marking was the exchange for Venetia.

The bold, oval postmark on the back that reads

"distribuzione I" tells us that this letter was sent out with a mail

carrier with the first distribution of mail on that day. Yes, you heard

that right. Many cities in Europe sent mail out to be delivered to

their customers multiple times each day. But, we must consider that

mail was the most common and accessible means of communication at the

time. There were no phones - postal mail was a vital service that was

taken very seriously in the 1860s.

Italy and Austria were not playing well together

But wait! There's more...

There was another reason the US Consulate in Florence did not prepay the postage to send the letter to Venezia. It just so happened that a person couldn't prepay that mail. Austria and Italy had not yet come up with a new postal agreement after the War of 1859. As a result, a person in Italy could only pay for a letter to get to the border. After that, the letter would travel through Austrian territory with the internal postage unpaid. The recipient would have to pay that amount to receive the letter.

Postage rates for mail in Venetia and Austria was based on both weight and distance. A simple letter could weigh as much as one loth (15.625 grams), but that simple letter would then be given a postage rate based on how far it had to travel. The first letter shown above did not have to travel more than 75 kilometers from the border with the Kingdom of Italy. The second had to travel over 150 km from the border to get to Vienna.

Each of these letters shown here have a 20 centesimi Italian stamp that paid the postage within Italy to its border with Venetia. The numerical markings told the mail carrier to collect five and fifteen kreuzer, respectively, from the recipient for the internal Austrian mail services.*

* note: the first cover is probably rated in soldi, rather than kreuzer, but using kreuzer serves for the discussion.

One more baseline

Before we close the story on our letter from the US to Italy via the UK, we need one more baseline example. Shown above is a letter that was mailed in the mid-1860s from France to Austria. The postage rate was 60 centimes, which is properly paid by the postage stamps. All of the markings for a typical, paid letter from France to Austria can be found on this letter. But....

There is an ink scrawl that is the number "5." I have circled that marking in red on this envelope. This told the letter carrier to collect 5 kreuzer from the recipient on delivery. Remember, five kreuzer would be the proper postage rate for internal Austrian mail that traveled less than 75 km.

It turns out - this

letter was also forwarded. Like our example, it was forwarded to a new

location but the forwarder did NOT prepay the postage. As a result, the

postal clerk made sure the carrier would know to collect postage by

putting this "5" on the front of the cover.

Since the US Consulate probably would not and could not prepay the postage from Florence to Venice, we should have expected to find an amount due when the carrier delivered this letter to Mrs. Abbott Lawrence. And, sure enough, here it is!

With all of the pen markings and the damage to this cover, it is not as obvious as one might expect. As a matter of fact, I did not notice this for quite some time myself. I knew this letter was forwarded to Venice, but I didn't quite understand how the postage was covered until I observed how Austrian postal clerks wrote their fives. Once I noticed that, it became easier to see the five on this item. So, Mrs. Abbott Lawrence had to pay 5 kreuzer (or soldi) to the carrier so she could read the news from Boston.

And

that, my friends, is the long explanation for how I piece together clues

in my effort to read the postal story a particular cover might have to

tell.

Matthew H. called attention the addressee of the letter from the UK to Italy, Giuseppe Sonnino in Naples. For those who have some knowledge of European history, the name Sonnino just might ring a bell or two. Sidney Sonnino was the Prime Minister of Foreign Affairs for Italy during World War I and also served briefly as Prime Minister in the early 1900s (twice).

While that is interesting, Giuseppe Sonnino of Naples cannot, with my brief bit of research, be easily connected to Sidney. Sidney's origins start in Livorno and Pisa and he had connections to the Anglican Church. Giuseppe, on the other hand, can be found as a rabbi for the Jewish community in Naples in the 1860s. There are enough references in Italian resources for Giuseppe that a person might be able to put some biographical material together over time. But, unless there is an extended family connection, I don't find a direct connection between the two.A bit closer to bonus material?

During

the presentation, someone asked if the addressee of this cover, Mrs.

Abbot Lawrence was one and the same as the person depicted in this painting by John Singer Sargant.

Unfortunately,

the answer is, once again, no. But, the relationship is a bit closer

this time around. Portrayed here is Mrs. Abbott Lawrence Rotch, who was

born in 1867, after the date this letter was received. She was married

to respected meteorologist Abbott Lawrence Rotch, who is fairly closely related to the letter's recipient (a nephew, perhaps).

Another possibility suggested was that the letter recipient was Katherine Bigelow Lawrence, spouse of Abbott Lawrence. Lawrence was an accomplished businessman

and gave Harvard University $50,000 to establish the

Lawrence Scientific School. He built lodging houses for the poor in

1845, and pushed for

education for the lower class. He was also the Vice Presidential

candidate in 1848 as part of an unsuccessful ticket with Zachary

Taylor. When Taylor won in the next election, Lawrence was not on the

ticket. When offered a cabinet position, he opted for a position as

minister to Great Britain. Abbott died in 1855.

However, the

information that time was spent in Europe makes it possible that

Katherine Lawrence could have been traveling there in 1865. But, there

is a problem with that too. Katherine Bigelow Lawrence died in 1860 according to this, and other, sources.

|

| painting of Katherine Bigelow Lawrence by Chester Harding at MFA Boston website |

This leads us to Abbott Bigelow Lawrence, Jr, who was married to Harriet White Paige Lawrence. Abbott Bigelow Lawrence was the son of Abbott Lawrence and Katherine Bigelow and was born in 1828, putting him and Harriet (born 1832) at about the right age for her to be the recipient of this particular letter.

So, let's introduce another character into this play. Timothy Bigelow Lawrence, brother of Abbott Bigelow Lawrence was a colonel in the Union army and was part of General E.D. Keyes' staff. Unfortunately, Col. Lawrence had a "tendency to deafness that became so much increased by exposure, and especially from the heavy firing he was so long surrounded by, as to impede and limit his usefulness in the field."* Thus, he moved on to a diplomatic appointment that he had delayed filling in his effort to serve with the armed forces.

*this quote and other information on T.B. Lawrence can be found in this printed memorial

that was initially in Boston Courier in 1869. It was printed for

private distribution in April, 1869 under the title T. Bigelow Lawrence

1869.

T.B. Lawrence served as the US Consulate General in Florence from 1861 to 1869.

Having a brother in Italy might be enough of a reason for Abbott and

Harriet Lawrence to make a visit to Italy (or maybe it was just

Harriet?). It also made it pretty easy to avail themselves of the

services of the Consulate General's office! It can be nice to have

connections.

So, yes, there are links to the family and to the women depicted in these two paintings, but neither of them was the recipient of this particular letter during travels in Europe. But, we still got to meet some interesting people in the process.

And, if our featured piece of postal history looked familiar to you this week, it was also featured in this Postal History Sunday from October 2022.

------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.