Postal History Sunday is celebrating one year of consistent, weekly posts on... you guessed it... a Sunday! On August 30, 2020, the second issue of PHS was published on the blog (the first and second offerings had a gap of a couple of weeks). Since then, I have yet to miss a week (this is the 54th PHS). That's as good a reason to celebrate as anything.

The title of the first PHS post was "Sharing Something You Enjoy," and I wanted to go back to that theme as part of the celebration for one year of posts.

Life has been difficult for all of us during the pandemic and with all of the various world events going on in recent years. Like many of you, I often find myself feeling worried, frustrated and depressed. I see people at each others' throats and that upsets me. My thought is that we need to find a balance between genuine concern for the world around us AND appreciation for the good things that make it worthwhile being concerned in the first place.

One proposal I can make? Share your unabashed enthusiasm for something you enjoy with others. That doesn't mean that you need to find someone who already appreciates what you do. Just share and show. Then listen and appreciate when others reciprocate. Maybe - throughout this process - we'll all learn something new and perhaps we'll gain more appreciation for good things AND each other.

--------------------------

So, this week I am going to do a show and tell of what is currently getting my attention in Postal History. Many of these things are due to be featured in their own Postal History Sunday, so you can consider some of this a preview. And, you will see reference links to several prior PHS entries you can explore if you are inclined to do so.

My focus today is simply expressing my enjoyment for each of the things I will show today.

French, but Not French

When your surname is "Faux" (pronounced "Fox" in our case), you typically have a fair amount of explaining to do when you meet new people. The most common question is whether I know if it means "fake" or "false" (pronounced like "foe"). C'mon! I've lived with this name my whole life, I suspect I have heard that a time or three.

The second most common question is whether I have French heritage. I suppose that is possible, but the family only traces heritage back to central Ireland. Still, it was enough for me to decide to select French as my language requirement in high school and college (no, they did not offer Irish Gaelic). In any event, these are just a couple of the reasons why I have found myself attracted to French postal history in the 1850s to 1870s.

That's enough to start to explain why this 1861 letter from St Etienne in France to Roulers in Belgium might attract my attention.

But, there is more to it than that. I find that postal history builds and branches from the places you have been before in the hobby. I can actually show you some of those branches with this single item.

In July, I shared a letter that traveled from Belgium TO St Etienne in France. The simple connection to a community for which I had done a little research was enough to give me a head start on this one. And, I have done a fair bit of study pertaining to mail between Belgium and France. So, I was able to determine that this letter was a triple weight letter, requiring (of course) three times the base rate of postage (120 centimes or 1 franc & 20 centimes).

Even better, I had recently written about "Sneaky Clues" in late July. Sometimes there are unobtrusive scrawls on covers that tell us something about the piece of mail in question. There is just such a scrawl on this cover that confirms for us that this letter weighed enough to require a triple rate. The rate was 40 centimes per 10 grams.

Can you find the "scrawl" I am referring to?

While I am not yet certain this first item will merit its own PHS entry one day, I can tell you that the next one will.

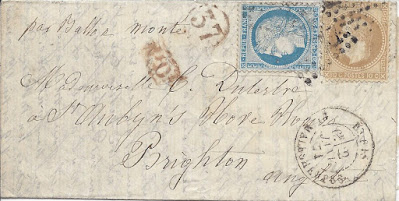

The folded letter above was mailed from Paris, France in 1871 to Brighton, England. The postage applied to the item paid the 30 centimes rate and, sure enough, there is the "P.D." which stands for "payée à destiné" (paid to destination).

At the time this letter was mailed in Paris, the city was surrounded by German armies and no one could leave the city - unless they flew OVER those who were laying siege. One of the most celebrated and studied stories in postal history has to be the use of manned balloons to carry mail out of the city and (hopefully) past the occupying forces.

This is one such letter. If you look at top left, you will see the words "par Ballon Monte" that provide us with the first clue that this might be one of the letters that left Paris via one of these flights.

I've even got a personal connection to this one. The name of the balloon was the "Newton." Now, ask me the name of the town I grew up in.

Paris?!? What? No.

Speaking of Germany

The postal history of Germany during the 1850s through 1870s can be very complex. During this period of time, the diverse German states began to merge and unify (some more willing than others). As this process progressed, the postal services saw significant changes. Any time that happens, there will be postal historians that try to make sense of it all - myself included.

Shown above is an 1861 letter from Mainz to Holland.

At the time this letter was sent, Mainz was in Hessian territory (Hesse was one of the German states). Unlike many of the other German states, the Hessian government did not provide a postal service. Instead, they relied on the Princely House of Thurn and Taxis for their mails.

Thurn

and Taxis has a long and distinguished history for carrying mail

starting in Italy around the year 1300. An item such as this one

provides a window into the last years of what was once the dominant mail

courier in much of Europe. That actually provides me with a bit of

difficulty, because I may have a hard time boiling it down to a

blog-sized piece.

Regardless, the story here is much too good for me to pass up having a Postal History Sunday that provides more focus in the next week or two.

Last week's PHS theme was a series of stamps that I admired when I was a very young collector. It should be no surprise to anyone that postal history and philately will have their popular sub-topics that often catch the imaginations of those who are beginners in the hobby. Sometimes, those beginners are hooked for life. It's not hard to explain.

Think of it this way - the New York Yankees often attract new baseball fans because they are often placed front and center in the most accessible media. Nearly everyone has heard of Beethoven and Mozart and that's probably where someone might start with classical music. Even if they move on to Berlioz as a favored composer, there is often still a soft spot for the music by the composer that introduced you to the genre.

That explains the item shown above. The German "Kaiser Yacht" series of stamps that were used in the German colonies in the early 1900s were the "storied" series of stamps that introduced me to German philately. While I may never study the postal history featuring these stamps seriously, I can still appreciate an item or two simply because I have a personal history of learning that traversed through this sort of thing.

The envelope shown above was mailed

from the then German colony of Kamerun to Geneve Switzerland. The

international letter rate (set by the Universal Postal Union) was 20

pfennig, which is overpaid here by 1 pfennig - there are seven copies of

the 3 pfennig stamp issued for Kamerun.

Lions, Tigers and... Other Stuff

I have mentioned the Tuscan Lion before and I do have a few items that feature that particular design. That would be part of the reason why I enjoy the old letter shown above. But, this one has so many other things that get my attention.

It travels from the Grand Duchy of Tuscany to London, England at a time just prior to the war that would lead Tuscany to join other Italian states as the Kingdom of Italy (1859/60). It properly pays a known postal rate. The markings are readable. The address panel is readable. It even has a marking that reads "Dopo la Partenza" - essentially a "Too Late" marking that indicates the letter arrived at the departure post office after the mail coach had left with the day's mails.

Perhaps the addressee will bring even more to the story

this postal artifact carries with it? Who knows what else I will find?

That's part of what makes this so much fun for me.

And I've always appreciated the Malaysian "Tiger Issues" because.. well... they have tigers on them. What other reason do you need?

Really. If a person likes tigers and that's what it takes to make them happy - an image of a tiger on a stamp that's on an old letter - then who are we to sneer at such a thing?

In my case, the familiarity with the stamp design gives me an opening to learn something about a geographical region I would otherwise have very little connection to. By taking a step from away from a familiar place, I open myself up to new things, new thoughts and different ideas - both within and outside of the postal history hobby.

And we should never forget the social history that comes along for the ride when we look at postal history. C.F. Adae served as the consulate in Cincinnati, Ohio for several German states during the late 1850s and through much of the 1860s.

The envelope shown above was one of multiple designs used by Adae for his mail. My interest in this particular item stems, once again, from prior experience. I was first introduced to this personality and the preprinted envelopes by this item from Cincinnati to Wurrtemberg:

Oh look! There's that fancy 24 cent stamp the United States issued in 1861! I really like that design!

I

wonder if it is possible that the farmer will write a Postal History

Sunday that shows items sent by C.F. Adae? Odds are pretty good that it

will happen some day. Especially now that you all see he has not just

one, but TWO items he could share in such a post.

You Just Had to Mention Those 24 centers...

Now you're really going to get him started. And you wanted to quit reading and go about your normal Sunday business...

Actually, I can tell about when many people's eyes are ready to glaze over from postal history overload and we've gotten there. So, we'll close with one more preview for a future Postal History Sunday.

The envelope shown above was mailed from Williams Creek in British Columbia during the gold rush in that region. The letter includes postage stamps from British Columbia to pay for the internal postage and a 24 cent 1861 US stamp to pay the postage from the United States to Liverpool in England.

Western gold rushes always ushered in rapid changes for those regions where a strike occurred and that's part of what makes this particular postal item so enjoyable. We can explore the reasons for two different postal systems' stamps on one letter. We can look at the route and conditions of the roads from Williams Creek to settlements on the Pacific Ocean.

I can focus just on the rates and the

routes, or I can explore the ways this letter might have traveled from

here to there. If I want, I can dig into the Cariboo Gold Rush and

learn about some of the personalities that loomed large at the time this

letter was sent. I cven learn more about the geological formations

that provided prospectors with the opportunity to make a find.

That's what I enjoy - and I hope you appreciated at least of some of today's sharing.

Have a great remainder of the day and I will see you next week for Postal History Sunday.